July 28, 2014

Today the French Quarter is one of the world's premier adult party destinations, and children are not generally part of the scene. That has not always been the case, though. Prior to the mid-20th century, kids were an ever-present part of the Quarter's environment. Notable New Orleanians who spent their childhoods in the Quarter include mid-19th-century chess great Paul Morphy, composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk, clarinetist Pete Fountain and exercise guru Richard Simmons.

From the founding of New Orleans in 1718 through the 18th century, the Quarter constituted the city in its entirety. As the city grew dramatically in the 19th century, the Quarter became one of the most densely populated areas in the entire South. Residents were mostly of French, African or Spanish descent, joined later by Italians, and virtually all were Roman Catholic. Having numerous children enhanced a family's church and social status, and most families abided by the church's tenet with regard to children.

Most people's lives revolved around family and the Catholic Church, and the St. Louis Cathedral was the center of religious life in the Quarter. Mothers looked after their families' church life and required attendance for the children. Aside from holidays like Easter and Christmas, there were also childhood rites of passage like baptisms, catechism lessons and first communions. Masses were always accompanied by a hubbub of babies crying and older youngsters fidgeting and playing while parents tried to quiet them, and pranks in the cathedral were not uncommon in the early 19th century - unsuspecting churchgoers might find crawfish or ink in the holy water fonts.

The first school in New Orleans was established for boys in 1725 by a Capuchin priest at 617 St. Ann St., where the Place d'Armes Hotel now stands. Before the school closed in 1740, lessons included reading, writing, French, Latin, religion and music. In 1727 Ursuline nuns arrived in the city to establish a hospital and teach the early settlement's young girls. Their convent was completed at Chartres and Ursuline Sts. in 1734, but the building quickly decayed, and two decades later a new building was completed, which is still standing today. Lessons were similar to those taught to boys, with the addition of sewing and embroidery. After the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, English was added to the Ursuline curriculum. The sisters left the French Quarter in 1824 for a site near the present-day Industrial Canal; since 1912 the convent has been Uptown on State Street. The original French Quarter convent is now a museum open to the public Monday through Saturday.

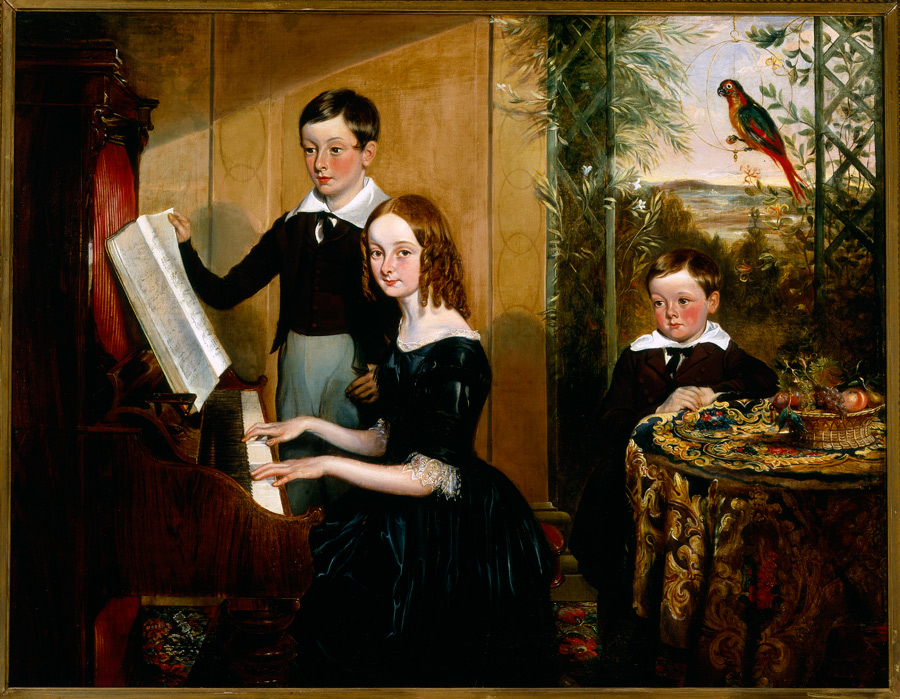

Other important French Quarter Catholic schools included the Academy of the Sacred Heart, which operated on Dumaine near Dauphine before moving to St. Charles Ave. in 1886, and the St. Louis Cathedral School on St. Ann, which was in session from 1914 until 2013. African American girls were taught at St. Mary's Academy by the Sisters of the Holy Family, an order for African American women founded in New Orleans by Henriette DeLille. The order took over the Orleans Theater and Ballroom, built in 1817 on Orleans at Bourbon St., in 1881 and used it as a convent and school until it moved in the 1960s. In addition to Catholic schools, small, privately run lay schools were available in the Quarter, including a few for African Americans. The curriculum at these schools was similar to that at Catholic schools, including subjects like language (French), reading, writing, arithmetic, drawing and music, along with good manners, the Bible and catechism. In the early Crescent City, education typically focused on teaching good manners and music, and many early 19th-century children - especially girls, due to the high cost of education - were taught at home, where they also learned basic skills like reading and arithmetic. English was frequently taught as a second language.

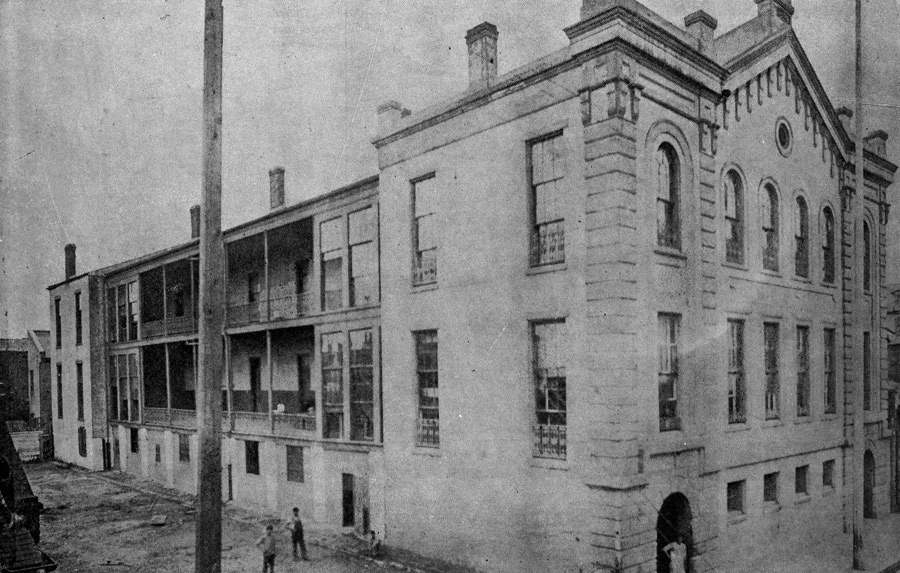

New Orleans opened its first public schools in the 1840s, and by 1859 more than 2,500 students were enrolled in French Quarter schools. They were separated by sex and race, and most classes were taught in English. One such school in the Quarter was St. Philip Public School, which opened in 1850 and lasted until 1931. It was on St. Philip St. between Royal and Bourbon, the site now occupied by KIPP McDonogh 15 School for the Creative Arts. Among French Quarter public high schools was the Lower Girls' High School at Royal and Governor Nicholls Sts., which was the first school in the South to desegregate during Reconstruction. Central High School for boys was located in the 200 block of Burgundy (where the back of the New Orleans Athletic Club now stands) during the late 19th century. Following Reconstruction, there were no public high schools for African American students in the city until 1914.

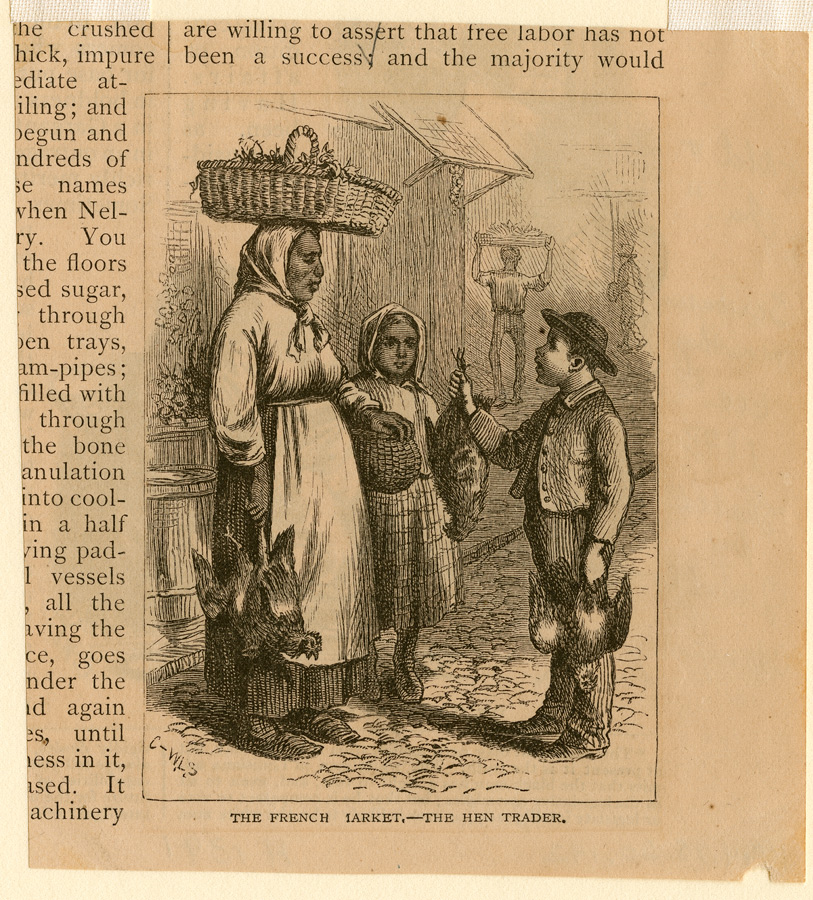

Most children went no further with their education than elementary school, after which they typically went to work to help provide for their families. Some kids went to work in small shops or served as street vendors, key figures in retail in the Quarter until well into the 20th century. Delivery boys were always in demand, and Italian children frequently went to work in the French Market, where by the late 19th century Italian immigrants dominated the fruit and vegetable stalls.

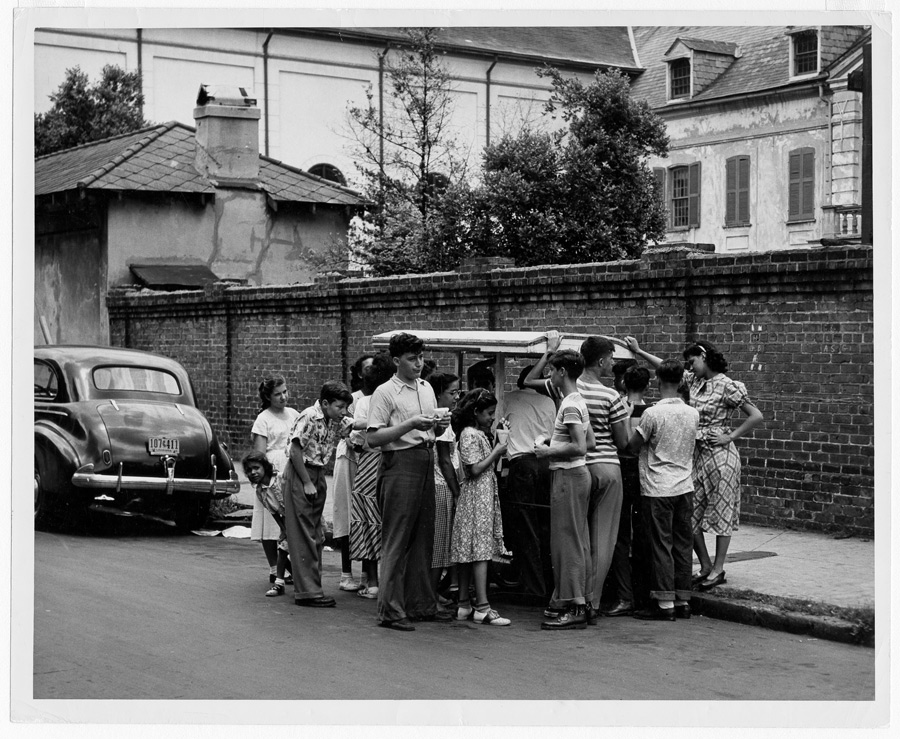

But there was always more to life than work - and the French Quarter was one big playground for kids, from the streets to Jackson Square and even the riverfront wharves. There were plenty of corner stores where kids could buy snacks, sweets, ice cream and snowballs. Girls might play hopscotch on the banquettes, or sidewalks, or play with dolls on galleries or in courtyards. Boys played stickball or roughhoused in the streets, and it was not unusual for them to get into fistfights.

Frequently, groups of children could be found wandering through the streets, beating toy drums or blowing toy horns. During holidays like Christmas and Mardi Gras, the din became deafening. Some children, especially African Americans, formed improvised ragtag "spasm" bands that are part of the jazz tradition.

One popular and noisy celebration that has fallen out of popularity was the January 8th anniversary of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans. Commemorating the date went out of fashion by the 1860s - about the same time that Halloween, a Celtic American celebration, began to take root. Halloween festivities might last well into the night - at one time All Saints Day was a school holiday, allowing children to accompany parents to cemeteries to freshen up family tombs.

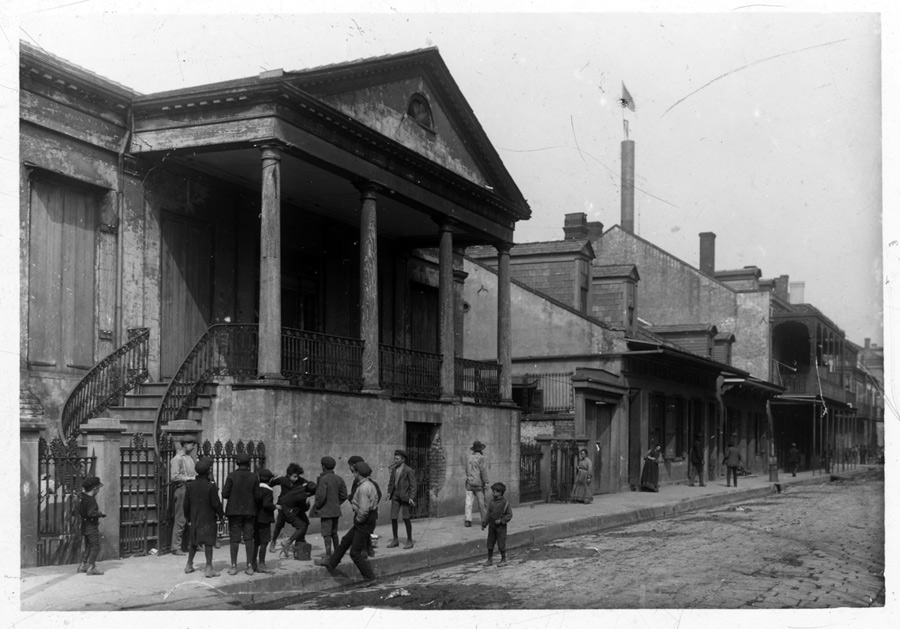

Through the19th century, the French Quarter had its share of homeless children and teenagers roaming the streets, as was common in most American cities, but the rise of compulsory education, truant officers and social workers helped curb the problem by the 20th century. Schools grew bigger and youngsters, especially those of high school age, began to take the streetcars to schools outside of the Quarter.

Today the resident population of the French Quarter is much smaller than it was prior to the mid-20th century. Youngsters seen on the streets of the Quarter today are far more likely to be on vacation, with their families, than they are to be residents.

From the founding of New Orleans in 1718 through the 18th century, the Quarter constituted the city in its entirety. As the city grew dramatically in the 19th century, the Quarter became one of the most densely populated areas in the entire South. Residents were mostly of French, African or Spanish descent, joined later by Italians, and virtually all were Roman Catholic. Having numerous children enhanced a family's church and social status, and most families abided by the church's tenet with regard to children.

Most people's lives revolved around family and the Catholic Church, and the St. Louis Cathedral was the center of religious life in the Quarter. Mothers looked after their families' church life and required attendance for the children. Aside from holidays like Easter and Christmas, there were also childhood rites of passage like baptisms, catechism lessons and first communions. Masses were always accompanied by a hubbub of babies crying and older youngsters fidgeting and playing while parents tried to quiet them, and pranks in the cathedral were not uncommon in the early 19th century - unsuspecting churchgoers might find crawfish or ink in the holy water fonts.

The first school in New Orleans was established for boys in 1725 by a Capuchin priest at 617 St. Ann St., where the Place d'Armes Hotel now stands. Before the school closed in 1740, lessons included reading, writing, French, Latin, religion and music. In 1727 Ursuline nuns arrived in the city to establish a hospital and teach the early settlement's young girls. Their convent was completed at Chartres and Ursuline Sts. in 1734, but the building quickly decayed, and two decades later a new building was completed, which is still standing today. Lessons were similar to those taught to boys, with the addition of sewing and embroidery. After the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, English was added to the Ursuline curriculum. The sisters left the French Quarter in 1824 for a site near the present-day Industrial Canal; since 1912 the convent has been Uptown on State Street. The original French Quarter convent is now a museum open to the public Monday through Saturday.

Other important French Quarter Catholic schools included the Academy of the Sacred Heart, which operated on Dumaine near Dauphine before moving to St. Charles Ave. in 1886, and the St. Louis Cathedral School on St. Ann, which was in session from 1914 until 2013. African American girls were taught at St. Mary's Academy by the Sisters of the Holy Family, an order for African American women founded in New Orleans by Henriette DeLille. The order took over the Orleans Theater and Ballroom, built in 1817 on Orleans at Bourbon St., in 1881 and used it as a convent and school until it moved in the 1960s. In addition to Catholic schools, small, privately run lay schools were available in the Quarter, including a few for African Americans. The curriculum at these schools was similar to that at Catholic schools, including subjects like language (French), reading, writing, arithmetic, drawing and music, along with good manners, the Bible and catechism. In the early Crescent City, education typically focused on teaching good manners and music, and many early 19th-century children - especially girls, due to the high cost of education - were taught at home, where they also learned basic skills like reading and arithmetic. English was frequently taught as a second language.

New Orleans opened its first public schools in the 1840s, and by 1859 more than 2,500 students were enrolled in French Quarter schools. They were separated by sex and race, and most classes were taught in English. One such school in the Quarter was St. Philip Public School, which opened in 1850 and lasted until 1931. It was on St. Philip St. between Royal and Bourbon, the site now occupied by KIPP McDonogh 15 School for the Creative Arts. Among French Quarter public high schools was the Lower Girls' High School at Royal and Governor Nicholls Sts., which was the first school in the South to desegregate during Reconstruction. Central High School for boys was located in the 200 block of Burgundy (where the back of the New Orleans Athletic Club now stands) during the late 19th century. Following Reconstruction, there were no public high schools for African American students in the city until 1914.

Most children went no further with their education than elementary school, after which they typically went to work to help provide for their families. Some kids went to work in small shops or served as street vendors, key figures in retail in the Quarter until well into the 20th century. Delivery boys were always in demand, and Italian children frequently went to work in the French Market, where by the late 19th century Italian immigrants dominated the fruit and vegetable stalls.

But there was always more to life than work - and the French Quarter was one big playground for kids, from the streets to Jackson Square and even the riverfront wharves. There were plenty of corner stores where kids could buy snacks, sweets, ice cream and snowballs. Girls might play hopscotch on the banquettes, or sidewalks, or play with dolls on galleries or in courtyards. Boys played stickball or roughhoused in the streets, and it was not unusual for them to get into fistfights.

Frequently, groups of children could be found wandering through the streets, beating toy drums or blowing toy horns. During holidays like Christmas and Mardi Gras, the din became deafening. Some children, especially African Americans, formed improvised ragtag "spasm" bands that are part of the jazz tradition.

One popular and noisy celebration that has fallen out of popularity was the January 8th anniversary of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans. Commemorating the date went out of fashion by the 1860s - about the same time that Halloween, a Celtic American celebration, began to take root. Halloween festivities might last well into the night - at one time All Saints Day was a school holiday, allowing children to accompany parents to cemeteries to freshen up family tombs.

Through the19th century, the French Quarter had its share of homeless children and teenagers roaming the streets, as was common in most American cities, but the rise of compulsory education, truant officers and social workers helped curb the problem by the 20th century. Schools grew bigger and youngsters, especially those of high school age, began to take the streetcars to schools outside of the Quarter.

Today the resident population of the French Quarter is much smaller than it was prior to the mid-20th century. Youngsters seen on the streets of the Quarter today are far more likely to be on vacation, with their families, than they are to be residents.