March 07, 2022

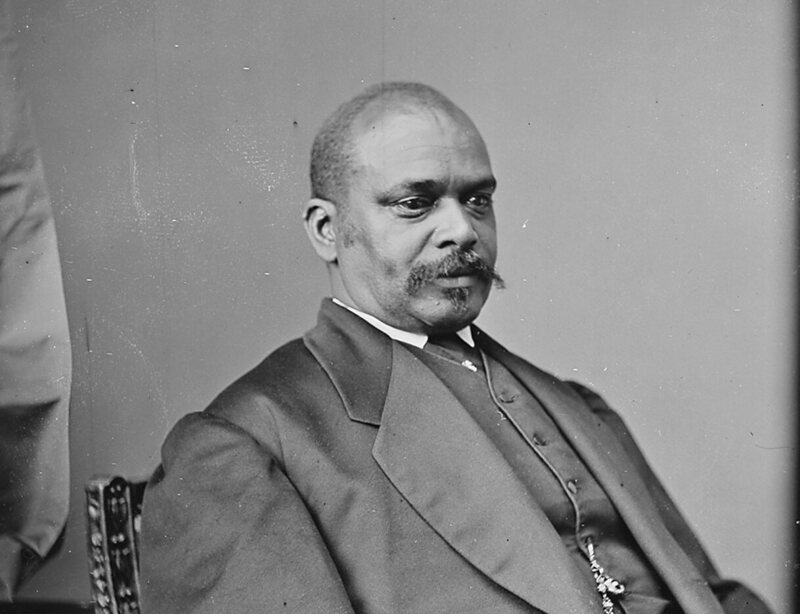

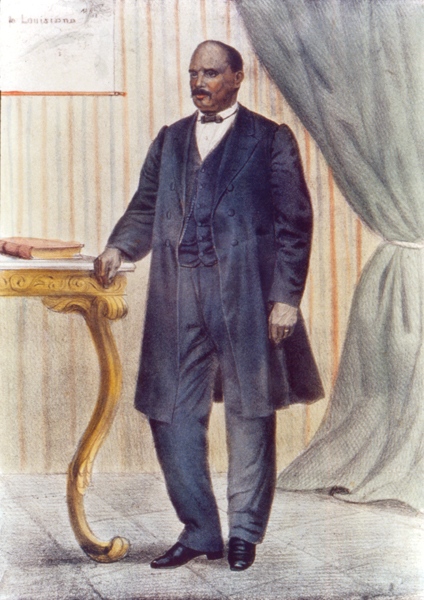

A significant political figure in Reconstructionist Louisiana, Oscar James Dunn, rose to prominence after the Civil War, becoming the first black lieutenant governor, serving Louisiana from 1868 to 1871. After his untimely death in 1871, Dunn faded into obscurity. Until recently, there were no monuments, statues, or streets named for him in New Orleans. In Jul. 2021, our City Council honored him by rededicating Washington Artillery Park, the elevated square which overlooks Jackson Square from the Mississippi River Levee, renaming it Oscar Dunn Park for this hero who was born into slavery and became the United States’ first black lieutenant governor.

Oscar Dunn was born to a slave mother in 1822. Dunn’s mother fell in love with a free man of color and in 1831, Oscar, his little sister, and his mother were purchased for $800 by his new stepfather, James Dunn. In 1832, James Dunn emancipated his family, officially making them free people of color. Oscar adopted his stepfather’s first and last names, becoming Oscar James Dunn. Now free, Oscar could attend school, a privilege denied to the state’s enslaved population. Despite his academic excellence, at 14 he was apprenticed to a master plasterer.

During the Civil War, Dunn did not serve in an active capacity. Near the end of the four-year conflict, he opened an employment agency where freedmen were hired out to residents of the New Orleans area. Working with the newly freed laboring class of African Americans, Dunn championed their struggle for freedom and became a strong advocate of land ownership for blacks, education for all children, and equal protection laws. He became secretary of the Advisory Committee of the Freedmen’s Saving and Trust Company of New Orleans and organized the People’s Bakery to foster economic independence.

Dunn’s desire to aid the cause of freedom and universal voters’ rights would be his stepping stone into politics and elective office. Reconstruction-era politics were hostile and often resulted in violent outbreaks across the defeated Confederacy as freedmen, carpetbaggers, and Radical Republicans began to seize power from the white supremacist establishment of the antebellum South. In 1867, Dunn was appointed to the Board of Aldermen of New Orleans based on his clear vision of the city’s civic needs. It was Dunn’s judgement as a councilman that brought about public education for the city and later for the state. He chaired a committee that set the age of children attending public schools between 6 and 18 years without distinction of color and placed responsibility for education on the Board of Aldermen.

After the Civil War, Dunn opened an information office where he negotiated labor contracts for freed men to ensure they were actually paid for their work. A leader among the Prince Hall Freemasons and within the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Dunn joined the executive committee of the Friends of Universal Suffrage which advocated for civil and voting rights for people of color in Louisiana. Dunn was among the first black men appointed to political office within Louisiana’s Reconstruction government and the first black person to serve in a judicial capacity in the state. In office, Dunn opposed the re-enslavement of black children through agricultural apprenticeships and was a fierce defender of civil rights.

In 1868, Dunn was elected as Louisiana’s lieutenant governor, the first black man to hold that office in American history. His role in community organizing during the 1860s had made him a fixture of the state’s political scene, and in office he fought back against corruption while boldly championing causes including suffrage, civil rights, and school integration. Dunn was twenty years older than Governor Warmoth and initially he believed that the young Yankee from New York wanted equality between whites and blacks. Shortly, Governor Warmoth betrays Lieutenant Governor Dunn by vetoing the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This created discord within Louisiana’s Radical Republican party, a progressive party intent on extending civil rights to African Americans as they realized that Warmoth was working against their interests. Opposing them were the Democrats, the ex-Confederates who didn’t accept Governor Warmoth because they viewed him as a carpetbagger. When Warmoth was unable to fulfill his duties, Dunn stepped in and performed so well that even his bitter opponents in the Democratic press complimented his skills. The strife between Governor Warmoth and Lieutenant Governor Dunn widened when Warmoth was unable to control the Executive Committee and its leadership fell to Dunn. When Dunn captured the Republican State Convention’s chairmanship, some historians claim that he was on track to become the first black governor of Louisiana in the 1872 election. From that post, many believed he would be elected to the US Senate and rumors were flying that the President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant, was considering Dunn for Vice President.

By 1871, Dunn used his bipartisan respect to lead the faction to impeach Governor Warmoth. Just before Warmoth’s trial, Dunn was invited to a public dinner where he became violently ill and died at the age of 49, leading many to speculate that he had been poisoned. The day of his funeral was declared a day of mourning, and all city government offices were closed. Benevolent societies, military, and police units formed the largest recorded funeral procession in the city’s history. The twelve-block-long funeral procession was reportedly witnessed by approximately fifty thousand people along Canal St. The Louisiana State House, public schools, and all federal buildings were closed as a sign of respect. Dunn was interred at St. Louis Cemetery No. 3.

Saunter over to Oscar Dunn Park at 700 Decatur St. in the French Market District and take in the beautifully iconic view of the river and the cathedral. Tip your hat in gratefulness to honor the man who fought fiercely for civil rights.

Oscar Dunn was born to a slave mother in 1822. Dunn’s mother fell in love with a free man of color and in 1831, Oscar, his little sister, and his mother were purchased for $800 by his new stepfather, James Dunn. In 1832, James Dunn emancipated his family, officially making them free people of color. Oscar adopted his stepfather’s first and last names, becoming Oscar James Dunn. Now free, Oscar could attend school, a privilege denied to the state’s enslaved population. Despite his academic excellence, at 14 he was apprenticed to a master plasterer.

During the Civil War, Dunn did not serve in an active capacity. Near the end of the four-year conflict, he opened an employment agency where freedmen were hired out to residents of the New Orleans area. Working with the newly freed laboring class of African Americans, Dunn championed their struggle for freedom and became a strong advocate of land ownership for blacks, education for all children, and equal protection laws. He became secretary of the Advisory Committee of the Freedmen’s Saving and Trust Company of New Orleans and organized the People’s Bakery to foster economic independence.

Dunn’s desire to aid the cause of freedom and universal voters’ rights would be his stepping stone into politics and elective office. Reconstruction-era politics were hostile and often resulted in violent outbreaks across the defeated Confederacy as freedmen, carpetbaggers, and Radical Republicans began to seize power from the white supremacist establishment of the antebellum South. In 1867, Dunn was appointed to the Board of Aldermen of New Orleans based on his clear vision of the city’s civic needs. It was Dunn’s judgement as a councilman that brought about public education for the city and later for the state. He chaired a committee that set the age of children attending public schools between 6 and 18 years without distinction of color and placed responsibility for education on the Board of Aldermen.

After the Civil War, Dunn opened an information office where he negotiated labor contracts for freed men to ensure they were actually paid for their work. A leader among the Prince Hall Freemasons and within the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Dunn joined the executive committee of the Friends of Universal Suffrage which advocated for civil and voting rights for people of color in Louisiana. Dunn was among the first black men appointed to political office within Louisiana’s Reconstruction government and the first black person to serve in a judicial capacity in the state. In office, Dunn opposed the re-enslavement of black children through agricultural apprenticeships and was a fierce defender of civil rights.

In 1868, Dunn was elected as Louisiana’s lieutenant governor, the first black man to hold that office in American history. His role in community organizing during the 1860s had made him a fixture of the state’s political scene, and in office he fought back against corruption while boldly championing causes including suffrage, civil rights, and school integration. Dunn was twenty years older than Governor Warmoth and initially he believed that the young Yankee from New York wanted equality between whites and blacks. Shortly, Governor Warmoth betrays Lieutenant Governor Dunn by vetoing the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This created discord within Louisiana’s Radical Republican party, a progressive party intent on extending civil rights to African Americans as they realized that Warmoth was working against their interests. Opposing them were the Democrats, the ex-Confederates who didn’t accept Governor Warmoth because they viewed him as a carpetbagger. When Warmoth was unable to fulfill his duties, Dunn stepped in and performed so well that even his bitter opponents in the Democratic press complimented his skills. The strife between Governor Warmoth and Lieutenant Governor Dunn widened when Warmoth was unable to control the Executive Committee and its leadership fell to Dunn. When Dunn captured the Republican State Convention’s chairmanship, some historians claim that he was on track to become the first black governor of Louisiana in the 1872 election. From that post, many believed he would be elected to the US Senate and rumors were flying that the President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant, was considering Dunn for Vice President.

By 1871, Dunn used his bipartisan respect to lead the faction to impeach Governor Warmoth. Just before Warmoth’s trial, Dunn was invited to a public dinner where he became violently ill and died at the age of 49, leading many to speculate that he had been poisoned. The day of his funeral was declared a day of mourning, and all city government offices were closed. Benevolent societies, military, and police units formed the largest recorded funeral procession in the city’s history. The twelve-block-long funeral procession was reportedly witnessed by approximately fifty thousand people along Canal St. The Louisiana State House, public schools, and all federal buildings were closed as a sign of respect. Dunn was interred at St. Louis Cemetery No. 3.

Saunter over to Oscar Dunn Park at 700 Decatur St. in the French Market District and take in the beautifully iconic view of the river and the cathedral. Tip your hat in gratefulness to honor the man who fought fiercely for civil rights.