September 30, 2021

America’s oldest and best loved public market writes its’ own history every day. With each new sunrise on Decatur Street, history repeats itself in fresh and new ways. For over two hundred years, New Orleans residents have enjoyed “making groceries” at the old French Market in the Quarter.

Though I have been a New Orleanian all my life, my view of the French Quarter remains as distant and mystified as a tourist’s. Growing up on the Westbank, my family would often visit the edge of Gretna to watch the cargo boats drift across the Mississippi. Sitting on the grassy levee in the all-consuming sunlight, the humidity sticking to my skin like wet sand, the rusted boats seemed to shimmer over the horizon, floating to the levees at the other end of the river.

Over the levees running along the edge of French Quarter rests one of the nation’s most historically rich and culturally diverse markets. The French Market, as we understand it today, began as a trading site for Native nations in the area, who traded with each other and with European explorers during the colonial period. As far into the late 1600s, the trading post was well regarded for its distinctive intermingling of languages and cultures, known among the Natives as “Bulbancha:” “the place of many tongues.” The Native market, established by the Oumas nation, sold goods to travelers exploring the southern riverfront, including Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the colonial governor of Louisiana. He later founded the city of New Orleans in 1718.

After the city’s founding, the Oumas and Tchouchoumas nations would structure markets along Bayou Saint John. By the 1760s, they consolidated trading spaces—the first of many unions which would expand the southern market into a thriving cultural hub. By the late 1700s, Spanish officials would erect the first informal, open-air market structure “between the water’s edge and the first row of houses” because of the Indian Law Compilation, an ordinance Spain upheld for their colonies. Butcher stands were later gathered at the riverbank, near the site of present-day Café du Monde. Around 1782, the first official market was erected at Chartres Street and Dumaine Street.

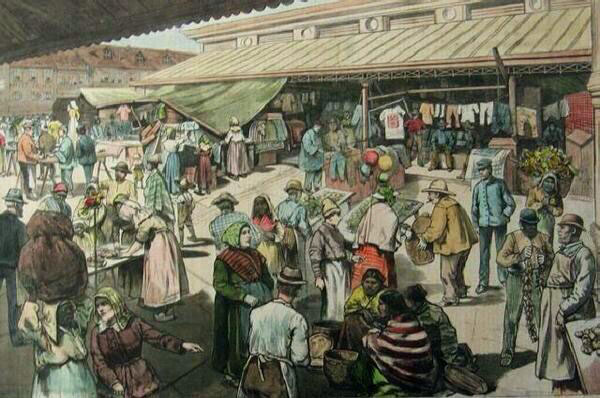

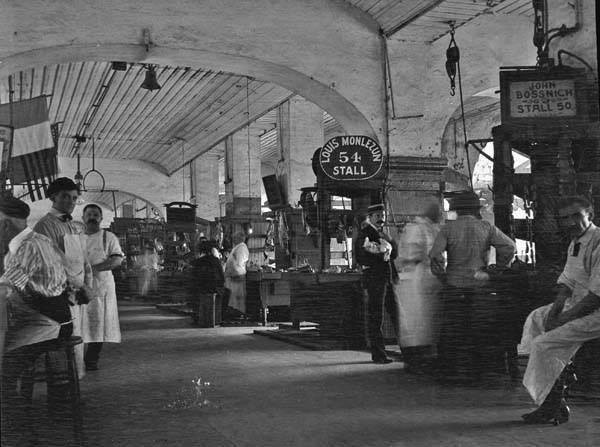

The August 1812 hurricane destroyed some early market structures. Though left without a market that year, in 1813 the “Meat Market” (“Le Halle des Boucheries”) would be formally erected, and survives to this day despite intensive renovations. By the 1850s, the Meat Market quarters would specifically be called the “French Market” because of its French and Creole butchers, whose “Old World sense” distinguished the market from other public competitors. The introduction of the Bazaar Market, designed by African American architect Joseph Abeiland, would see a multicultural flourishing of available product during the mid-to-late 1800s. Italian immigrants arrived in 1864, carrying with them their innovative and wildly popular muffulettas to the current day. Despite the market’s dingy surfaces and warping wooden buildings, its bustling soul of intercultural activity burned passionately in the poor immigrant vendors who ran it. Following the Great Depression, however, most of these markets would be renovated or demolished.

Writers and reporters soon flocked to the French Market to document its layered histories, hoping to unlock its immortal mysteries. Adding to New Orleans’ radiant literary past, the market became a tourist destination for Americans and Europeans alike during the antebellum period. In 1821, John James Audubon visited New Orleans and wrote of his love for the mixing of African, Spanish, French and English languages and cultures, each responding to the other in a fluid dance.

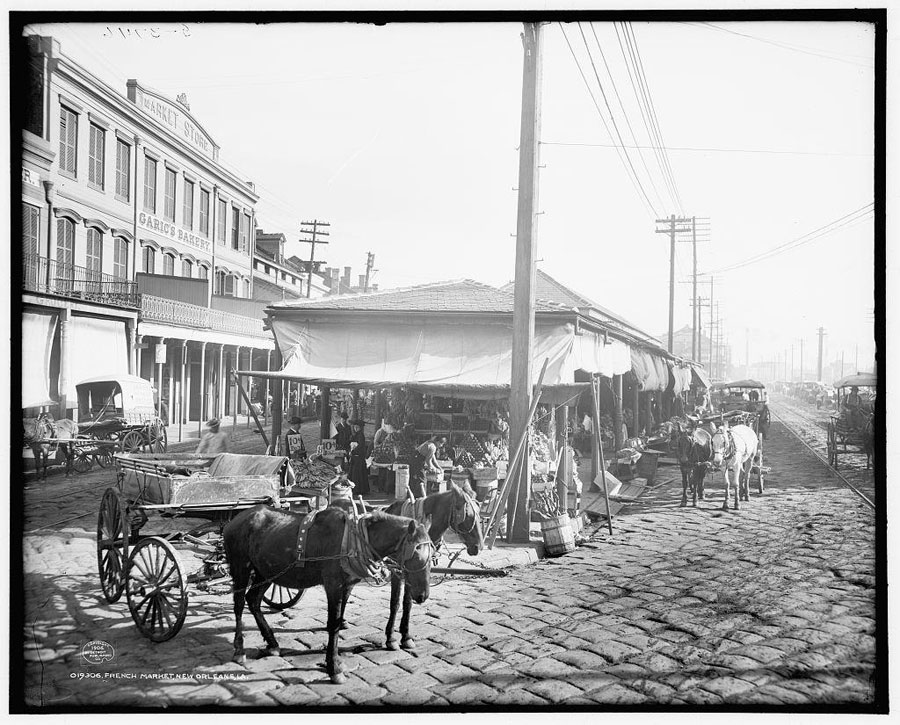

During the 1840’s, our port was the second largest port in the country and the fourth largest port in the world. Coffee was the main import crop and formed the basis of our port’s development. By 1864, Italian immigrants had arrived in significant numbers with many setting up businesses in the French Market. Throughout the 1890s, the French Market had a distinctive Italian flair to it. Central Grocery opened across the street on Decatur where they continue to serve their world-famous muffuletta.

After more than a century of success and profitability for the city and the vendors, the French Market arrived around 1890 at two extremes. The place was dirty, the buildings were in disrepair, immigrant market sellers were impoverished, yet it was at the busiest and most photogenic period of its history.

Greek-born Irish-Japanese writer Lafcadio Hearn followed his globetrotting heritage and lived in New Orleans for a decade, writing "As you approach the French Market, you go down in the social scale, and the price of dinner grows cheaper," and that a visitor “might here study the world.… Every race that the world boasts is here, and a good many races that are nowhere else.”

Turning to the 20th century, Missouri-born journalist Martha Reinhard Field published “The Story of the Old French Market” at the height of the First World War while writing for the Times-Picayune. Publishing as “Catherine Cole,” she became the first New Orleanian female professional newspaper reporter. In her travel pamphlet, Field reported that the French Market’s story centers on coffee. In Field’s French Market, the vendors’ routine requests for coffee...“Café au lait?” “Café noir?” fell like a spell from their mouths, a “familiar monotone” bouncing from the aging, greyed walls. The scent of coffee filled the atmosphere with a “spicy fragrance” that could awaken the city’s ancient ghosts in a ritualistic communion.

But no coffee establishment currently operating in New Orleans could have begun without the efforts of Rose Nicaud. A former slave who bought her freedom in the early 1800s, she sold coffee on Sundays from a portable cart she moved along the market. At the end of Field’s pamphlet, she mentions “Old Rose” and her “sparkling coffee.” Her coffee stand inspired other female former slaves to pursue freedom by the cup. With its bitterly brewed flavor, flowing majestically as ink, Field regards her coffee as “like the benediction that follows after prayer.” After generations of Africans and Creoles sold their own coffee, Café du Monde became the French Market’s oldest official tenant in 1862. The nationally famous French Market Coffee company, established by the Bartlett and Dodge families in 1890, moved to 800 Magazine St. in 1920. The historic “Morning Call” stand found its debut beside the Joan of Arc statue in the 1930s, a small beacon of security during Depression-era America.

The Great Depression saw further market uncertainties. Renovated entirely by the Works Progress Administration in a city-funded project to beautify the Quarter, the market modernized throughout the 1930s. Organized by the 1932 French Market Corporation, the market’s extensive renovations proved costly; by 1939, the city government stepped in to repay the corporation’s outstanding debts. Through the 20th century, the city’s government and the corporation went through several lease arrangements to finance the market’s continued developments, eventually settling on a 40-year lease with the corporation in 1971. To the dismay of some long-time visitors and vendors, the entire market was rebuilt, reconstructed, and sanitized through the 1970s, almost beyond recognition. But the market gained a parking lot, a Visitor’s Center, a Jazz National Park, and a flea market, where some of the city’s most unique and fashionable art and jewelry continue to be sold.

The French Market retains its soul, its vibrant intercultural character, in serving only the freshest products and the finest materials from vendors whose family traditions stretch as far back as the very roots of the market. At the city’s bicentennial, the New Orleans French Market Board extended a hand to the Louisiana Office of Indian Affairs, respecting the Native contribution to the French Market’s early establishment. The Times-Picayune also ran a column in 2018 which focused on 300 influential New Orleanians, among them the Creole Wild West, the first New Orleans Mardi Gras Indian tribe, and vendor Rose Nicaud.

Despite our post-COVID environment, the French Market shines a curious light on our need for connectivity, regardless of color or creed, in a self-reforming space that is nevertheless tethered to its own history. Our enduring market does just that—as it has, and as it will, for as long as there remains a New Orleans to service. The French Market is still a destination for shopping and entertainment, and is always a great place to spend an afternoon. Café du Monde is a must-visit in the French Market area, as it is the oldest tenant of the market, dating back to 1862. Order some beignets and steaming café au lait and enjoy people watching as you sip.

Though I have been a New Orleanian all my life, my view of the French Quarter remains as distant and mystified as a tourist’s. Growing up on the Westbank, my family would often visit the edge of Gretna to watch the cargo boats drift across the Mississippi. Sitting on the grassy levee in the all-consuming sunlight, the humidity sticking to my skin like wet sand, the rusted boats seemed to shimmer over the horizon, floating to the levees at the other end of the river.

Over the levees running along the edge of French Quarter rests one of the nation’s most historically rich and culturally diverse markets. The French Market, as we understand it today, began as a trading site for Native nations in the area, who traded with each other and with European explorers during the colonial period. As far into the late 1600s, the trading post was well regarded for its distinctive intermingling of languages and cultures, known among the Natives as “Bulbancha:” “the place of many tongues.” The Native market, established by the Oumas nation, sold goods to travelers exploring the southern riverfront, including Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the colonial governor of Louisiana. He later founded the city of New Orleans in 1718.

After the city’s founding, the Oumas and Tchouchoumas nations would structure markets along Bayou Saint John. By the 1760s, they consolidated trading spaces—the first of many unions which would expand the southern market into a thriving cultural hub. By the late 1700s, Spanish officials would erect the first informal, open-air market structure “between the water’s edge and the first row of houses” because of the Indian Law Compilation, an ordinance Spain upheld for their colonies. Butcher stands were later gathered at the riverbank, near the site of present-day Café du Monde. Around 1782, the first official market was erected at Chartres Street and Dumaine Street.

The August 1812 hurricane destroyed some early market structures. Though left without a market that year, in 1813 the “Meat Market” (“Le Halle des Boucheries”) would be formally erected, and survives to this day despite intensive renovations. By the 1850s, the Meat Market quarters would specifically be called the “French Market” because of its French and Creole butchers, whose “Old World sense” distinguished the market from other public competitors. The introduction of the Bazaar Market, designed by African American architect Joseph Abeiland, would see a multicultural flourishing of available product during the mid-to-late 1800s. Italian immigrants arrived in 1864, carrying with them their innovative and wildly popular muffulettas to the current day. Despite the market’s dingy surfaces and warping wooden buildings, its bustling soul of intercultural activity burned passionately in the poor immigrant vendors who ran it. Following the Great Depression, however, most of these markets would be renovated or demolished.

Writers and reporters soon flocked to the French Market to document its layered histories, hoping to unlock its immortal mysteries. Adding to New Orleans’ radiant literary past, the market became a tourist destination for Americans and Europeans alike during the antebellum period. In 1821, John James Audubon visited New Orleans and wrote of his love for the mixing of African, Spanish, French and English languages and cultures, each responding to the other in a fluid dance.

During the 1840’s, our port was the second largest port in the country and the fourth largest port in the world. Coffee was the main import crop and formed the basis of our port’s development. By 1864, Italian immigrants had arrived in significant numbers with many setting up businesses in the French Market. Throughout the 1890s, the French Market had a distinctive Italian flair to it. Central Grocery opened across the street on Decatur where they continue to serve their world-famous muffuletta.

After more than a century of success and profitability for the city and the vendors, the French Market arrived around 1890 at two extremes. The place was dirty, the buildings were in disrepair, immigrant market sellers were impoverished, yet it was at the busiest and most photogenic period of its history.

Greek-born Irish-Japanese writer Lafcadio Hearn followed his globetrotting heritage and lived in New Orleans for a decade, writing "As you approach the French Market, you go down in the social scale, and the price of dinner grows cheaper," and that a visitor “might here study the world.… Every race that the world boasts is here, and a good many races that are nowhere else.”

Turning to the 20th century, Missouri-born journalist Martha Reinhard Field published “The Story of the Old French Market” at the height of the First World War while writing for the Times-Picayune. Publishing as “Catherine Cole,” she became the first New Orleanian female professional newspaper reporter. In her travel pamphlet, Field reported that the French Market’s story centers on coffee. In Field’s French Market, the vendors’ routine requests for coffee...“Café au lait?” “Café noir?” fell like a spell from their mouths, a “familiar monotone” bouncing from the aging, greyed walls. The scent of coffee filled the atmosphere with a “spicy fragrance” that could awaken the city’s ancient ghosts in a ritualistic communion.

But no coffee establishment currently operating in New Orleans could have begun without the efforts of Rose Nicaud. A former slave who bought her freedom in the early 1800s, she sold coffee on Sundays from a portable cart she moved along the market. At the end of Field’s pamphlet, she mentions “Old Rose” and her “sparkling coffee.” Her coffee stand inspired other female former slaves to pursue freedom by the cup. With its bitterly brewed flavor, flowing majestically as ink, Field regards her coffee as “like the benediction that follows after prayer.” After generations of Africans and Creoles sold their own coffee, Café du Monde became the French Market’s oldest official tenant in 1862. The nationally famous French Market Coffee company, established by the Bartlett and Dodge families in 1890, moved to 800 Magazine St. in 1920. The historic “Morning Call” stand found its debut beside the Joan of Arc statue in the 1930s, a small beacon of security during Depression-era America.

The Great Depression saw further market uncertainties. Renovated entirely by the Works Progress Administration in a city-funded project to beautify the Quarter, the market modernized throughout the 1930s. Organized by the 1932 French Market Corporation, the market’s extensive renovations proved costly; by 1939, the city government stepped in to repay the corporation’s outstanding debts. Through the 20th century, the city’s government and the corporation went through several lease arrangements to finance the market’s continued developments, eventually settling on a 40-year lease with the corporation in 1971. To the dismay of some long-time visitors and vendors, the entire market was rebuilt, reconstructed, and sanitized through the 1970s, almost beyond recognition. But the market gained a parking lot, a Visitor’s Center, a Jazz National Park, and a flea market, where some of the city’s most unique and fashionable art and jewelry continue to be sold.

The French Market retains its soul, its vibrant intercultural character, in serving only the freshest products and the finest materials from vendors whose family traditions stretch as far back as the very roots of the market. At the city’s bicentennial, the New Orleans French Market Board extended a hand to the Louisiana Office of Indian Affairs, respecting the Native contribution to the French Market’s early establishment. The Times-Picayune also ran a column in 2018 which focused on 300 influential New Orleanians, among them the Creole Wild West, the first New Orleans Mardi Gras Indian tribe, and vendor Rose Nicaud.

Despite our post-COVID environment, the French Market shines a curious light on our need for connectivity, regardless of color or creed, in a self-reforming space that is nevertheless tethered to its own history. Our enduring market does just that—as it has, and as it will, for as long as there remains a New Orleans to service. The French Market is still a destination for shopping and entertainment, and is always a great place to spend an afternoon. Café du Monde is a must-visit in the French Market area, as it is the oldest tenant of the market, dating back to 1862. Order some beignets and steaming café au lait and enjoy people watching as you sip.