August 02, 2013

Whether one believes in ghosts and vampires, or just imagines footsteps in the dark, the Crescent City's French Quarter, with its worn walls and overhanging galleries, helps one conjure up thoughts of such things. The Quarter is a wonderfully exotic place that can be made eerier by night, although long ago this was undoubtedly truer, since today's bright lighting tempers the gloom and shadow.

The full moon can be a respite from the darkness - but eerie as well. The 1935 MGM musical Naughty Marietta with Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy is set in 18th century New Orleans. Based upon Victor Herbert's 1910 operetta with lyrics by Rida Johnson Young and additional movie lyrics by Gus Kahn, the love song "'Neath a Southern Moon" leads off with the words "Riding thru the sky / at midnight / there's a witch upon / a magic broom. / There's danger in the / southern sky at midnight "..."

Prior to the late 19th century, limited artificial light meant that street life in the French Quarter - like everywhere else - occurred primarily during daylight hours, but as dark as streets were in the Quarter, they were even then a lure for nighttime activities. Illumination in early New Orleans was simply fire, which unlike today's steady electric gleam, danced and flickered. There were no streetlights, but some buildings had lanterns; candles and fireplaces glowed through shuttered doorways and windows; and lanterns or torches carried by pedestrians moved slowly through the dark, narrow, unpaved streets. A brisk autumn wind blowing into town through nearby swamps might make the dim lights and shadows waver all the more. Outside the Quarter, there were once dense forests and swamps where near-total darkness consumed the night, thrusting those abroad into a world of imagined terrors.

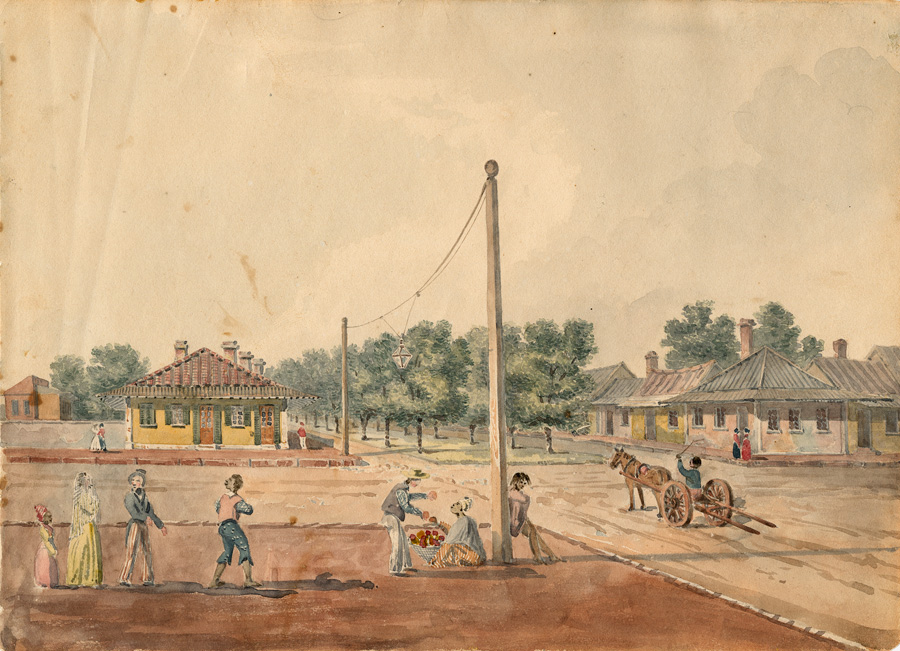

The first streetlights came to New Orleans under the order of Spanish Governor Francisco Luis Hector de Carondelet in the 1790s (Spain ruled Louisiana between 1762 and 1803). These were simple oil lamps suspended over streets from iron chains attached to the corners of houses or high posts at street intersections so as to be seen in a range. The light was dim but could still be perceived from a distance. To improve nighttime safety, Carondelet organized a small band of night watchmen.

Oil lamps and lanterns aboard ships brightened the Mississippi riverfront. The levee was enhanced by a gravel pathway and several rows of trees, providing a popular promenade. Here many people carried their own lanterns after dark; a tumble could be dangerous, since the murky river flowed close to the walkway.

Oil lamps remained in use into the mid-19th century, but their poor performance prompted the Daily Picayune of November 27, 1855, to complain that a large number of oil lamps did not burn at all, while others worked only a portion of the night, and those that were lit emitted a "dim, almost useless light "... well calculated to aid highwaymen and desperados, in vacant squares, dark recesses and obscure alleys."

Gaslight was introduced to New Orleans by English-born James Caldwell at his American Theater on Camp Street in 1824. Using English machinery he built the city's first gasworks in 1834. It served the entire city, and some of the first gas lit streets were in the densely populated French Quarter. By the 1860s there were over 2,500 city-owned streetlights - cast-iron lamps on posts situated about a block apart - all over town. Though they provided more light than the old oil lamps, they were still rather dismal, and in spite of complaints from the public, officials required that the lights be extinguished when the moon was full - even on cloudy nights. On these nights, however, the Quarter wasn't completely dark, since thousands of gas lamps flickered from private buildings. Some property owners even produced their own highly dangerous gas for home lighting.

This was an age of gaslight and shadow in the Quarter, and cast-iron galleries, which became popular in the 1850s, frequently blocked light to create spooky shadows. Dark silhouetted trees cast long shadows through dancing gaslight.

Electric arc streetlights arrived in New Orleans in 1882 and were soon in the French Quarter along the wharves, on Chartres and Royal Streets, around the French Opera House on Bourbon Street, in Jackson Square and throughout the French Market. Lights were either strung across street intersections like the old oil lamps, or hung over the street from tall iron standards. Electric wires were strung along the sides of buildings and under galleries. The quaint, cast-iron lights now seen throughout the Quarter replicate old gas lamps; they were installed as part of a lighting plan in the late 1920s when the Quarter was going through early stages of preservation and gentrification.

In ancient Europe, as nights grew longer during harvest time, there were festivals that evolved into our modern celebration of Halloween. Halloween's roots are more Celtic-American than French, but by the late 19th century witches and goblins were appearing in New Orleans while children were masking and carving jack-o'-lanterns from pumpkins - many bought at the French Market. Modern Halloween has overtaken the French Quarter, turning it into a nationally recognized haunt for costumed adult revelers.

The day after Halloween is All Saints' Day, when New Orleanians visit tombs and cemeteries. Unlike Halloween, it has roots reaching to the city's earliest history, since this Christian tradition was practiced by the French, and generally cooler weather on that day in New Orleans is a prime time for tidying up family tombs. As days grow shorter and cooler, the Crescent City emerges from its summer doldrums. In the early 19th century the months after All Saints' Day was regarded as "the season," which was marked by rounds of dinners, dances, elegant balls, opera and theater - not to mention good times in taverns and dance halls - leading to the Carnival season and culminating with Mardi Gras. Little in that respect has changed - although now it is much more brilliantly illuminated.

The full moon can be a respite from the darkness - but eerie as well. The 1935 MGM musical Naughty Marietta with Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy is set in 18th century New Orleans. Based upon Victor Herbert's 1910 operetta with lyrics by Rida Johnson Young and additional movie lyrics by Gus Kahn, the love song "'Neath a Southern Moon" leads off with the words "Riding thru the sky / at midnight / there's a witch upon / a magic broom. / There's danger in the / southern sky at midnight "..."

Prior to the late 19th century, limited artificial light meant that street life in the French Quarter - like everywhere else - occurred primarily during daylight hours, but as dark as streets were in the Quarter, they were even then a lure for nighttime activities. Illumination in early New Orleans was simply fire, which unlike today's steady electric gleam, danced and flickered. There were no streetlights, but some buildings had lanterns; candles and fireplaces glowed through shuttered doorways and windows; and lanterns or torches carried by pedestrians moved slowly through the dark, narrow, unpaved streets. A brisk autumn wind blowing into town through nearby swamps might make the dim lights and shadows waver all the more. Outside the Quarter, there were once dense forests and swamps where near-total darkness consumed the night, thrusting those abroad into a world of imagined terrors.

The first streetlights came to New Orleans under the order of Spanish Governor Francisco Luis Hector de Carondelet in the 1790s (Spain ruled Louisiana between 1762 and 1803). These were simple oil lamps suspended over streets from iron chains attached to the corners of houses or high posts at street intersections so as to be seen in a range. The light was dim but could still be perceived from a distance. To improve nighttime safety, Carondelet organized a small band of night watchmen.

Oil lamps and lanterns aboard ships brightened the Mississippi riverfront. The levee was enhanced by a gravel pathway and several rows of trees, providing a popular promenade. Here many people carried their own lanterns after dark; a tumble could be dangerous, since the murky river flowed close to the walkway.

Oil lamps remained in use into the mid-19th century, but their poor performance prompted the Daily Picayune of November 27, 1855, to complain that a large number of oil lamps did not burn at all, while others worked only a portion of the night, and those that were lit emitted a "dim, almost useless light "... well calculated to aid highwaymen and desperados, in vacant squares, dark recesses and obscure alleys."

Gaslight was introduced to New Orleans by English-born James Caldwell at his American Theater on Camp Street in 1824. Using English machinery he built the city's first gasworks in 1834. It served the entire city, and some of the first gas lit streets were in the densely populated French Quarter. By the 1860s there were over 2,500 city-owned streetlights - cast-iron lamps on posts situated about a block apart - all over town. Though they provided more light than the old oil lamps, they were still rather dismal, and in spite of complaints from the public, officials required that the lights be extinguished when the moon was full - even on cloudy nights. On these nights, however, the Quarter wasn't completely dark, since thousands of gas lamps flickered from private buildings. Some property owners even produced their own highly dangerous gas for home lighting.

This was an age of gaslight and shadow in the Quarter, and cast-iron galleries, which became popular in the 1850s, frequently blocked light to create spooky shadows. Dark silhouetted trees cast long shadows through dancing gaslight.

Electric arc streetlights arrived in New Orleans in 1882 and were soon in the French Quarter along the wharves, on Chartres and Royal Streets, around the French Opera House on Bourbon Street, in Jackson Square and throughout the French Market. Lights were either strung across street intersections like the old oil lamps, or hung over the street from tall iron standards. Electric wires were strung along the sides of buildings and under galleries. The quaint, cast-iron lights now seen throughout the Quarter replicate old gas lamps; they were installed as part of a lighting plan in the late 1920s when the Quarter was going through early stages of preservation and gentrification.

In ancient Europe, as nights grew longer during harvest time, there were festivals that evolved into our modern celebration of Halloween. Halloween's roots are more Celtic-American than French, but by the late 19th century witches and goblins were appearing in New Orleans while children were masking and carving jack-o'-lanterns from pumpkins - many bought at the French Market. Modern Halloween has overtaken the French Quarter, turning it into a nationally recognized haunt for costumed adult revelers.

The day after Halloween is All Saints' Day, when New Orleanians visit tombs and cemeteries. Unlike Halloween, it has roots reaching to the city's earliest history, since this Christian tradition was practiced by the French, and generally cooler weather on that day in New Orleans is a prime time for tidying up family tombs. As days grow shorter and cooler, the Crescent City emerges from its summer doldrums. In the early 19th century the months after All Saints' Day was regarded as "the season," which was marked by rounds of dinners, dances, elegant balls, opera and theater - not to mention good times in taverns and dance halls - leading to the Carnival season and culminating with Mardi Gras. Little in that respect has changed - although now it is much more brilliantly illuminated.