May 05, 2015

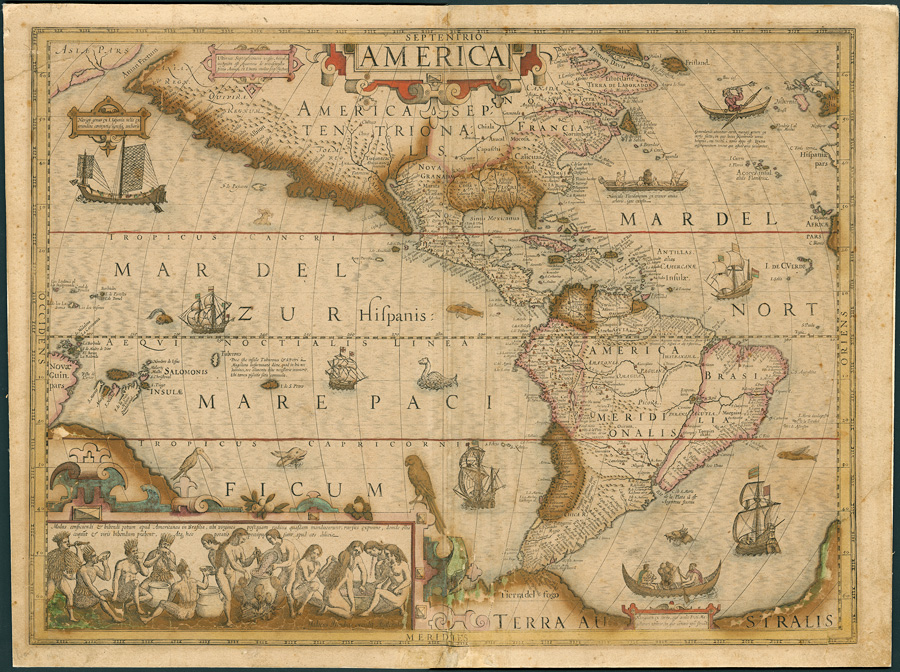

Filled with images of ships and sea monsters, one early seventeenth-century map of the Americas features a gigantic North America; so large, in fact, that it stretches across half the page and is comparatively larger than South America. Created by Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator (1512 - 1594), the map was originally printed in an atlas. The bottom left corner features a vignette of native women making a beverage - several are spitting into a pot, from which the men drink. The translated Latin caption reads: "Manner of obtaining and drinking draughts among the Americans in Brazil, where young women, after they have chewed up certain roots, spit it out again, and then they cook it and offer it for drinking to the men. And this drinking-bout was especially a stimulus of delight."

This antique map of America was purchased by General and Mrs. L. Kemper Williams, the founders of The Historic New Orleans Collection, and eventually became the museum's first accessioned item.

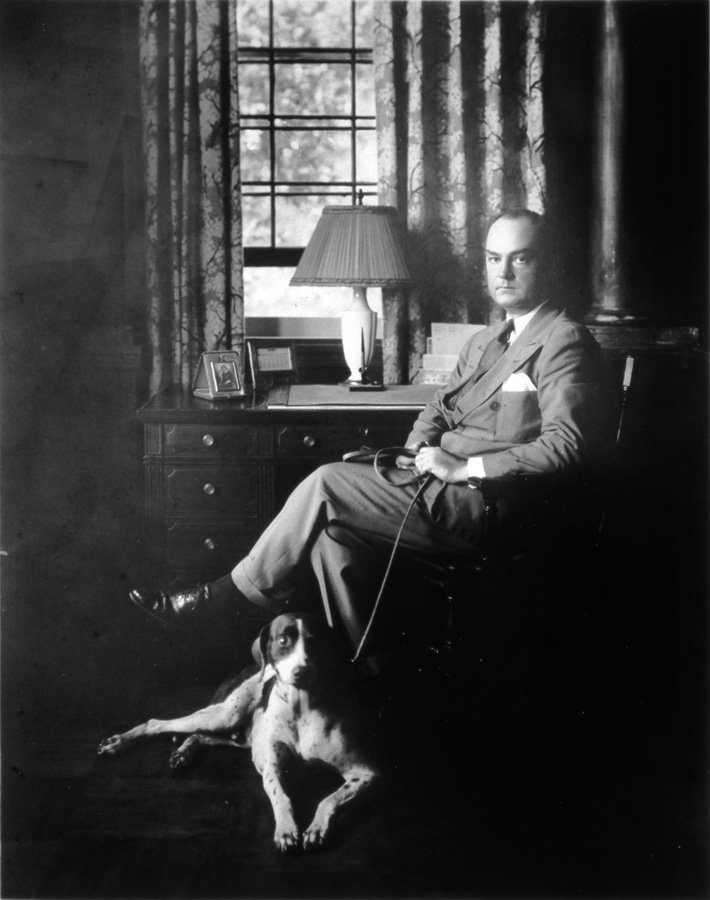

Lewis Kemper Williams, known as Kemper, was born September 23, 1887, in Patterson, Louisiana. His parents were cypress magnate Frank B. Williams and Emily Williamson Seyburn. During World War I, he served as a major in the United States Army. Over his lifetime, he also held various positions with Williams Inc., his family's company, ending as Chairman of the Board when he retired in 1971; later in life, he was also named the Honorary Consul of Monaco.

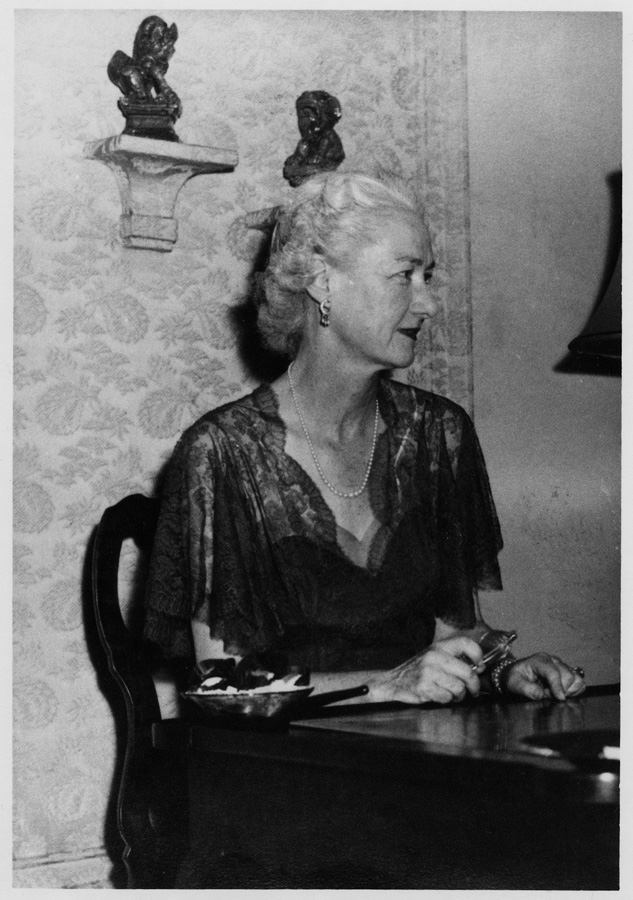

L. Kemper Williams married Leila Hardie Moore on October 2, 1920. Named after her mother, she was born in New Orleans on Lundi Gras, February 19, 1901, to Robert and Leila Hardie Moore. After living for ten years in Patterson, where the main sawmill of the family's lumber business was located, the couple moved to Audubon Street in New Orleans. In 1938, persuaded by architect and preservationist Richard Koch (1889 - 1971), the Williamses bought two properties in the French Quarter to help with revitalization efforts. Both properties - the Merieult House at 533 Royal Street and the adjacent Trapolin House, which fronted Toulouse Street - were in a similar state as the rest of the Vieux Carre - decrepit, and in need of a vast amount of work Koch had worked with the Williamses previously on their Audubon Street home. Koch is perhaps best known today for his work with the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) during the Depression, which documented endangered Louisiana buildings with the hope of restoration and preservation.

With the outbreak of World War II, Kemper resumed his work with the Army, eventually moving to Washington, D.C. with Leila. President Roosevelt named him a brigadier general in 1944.

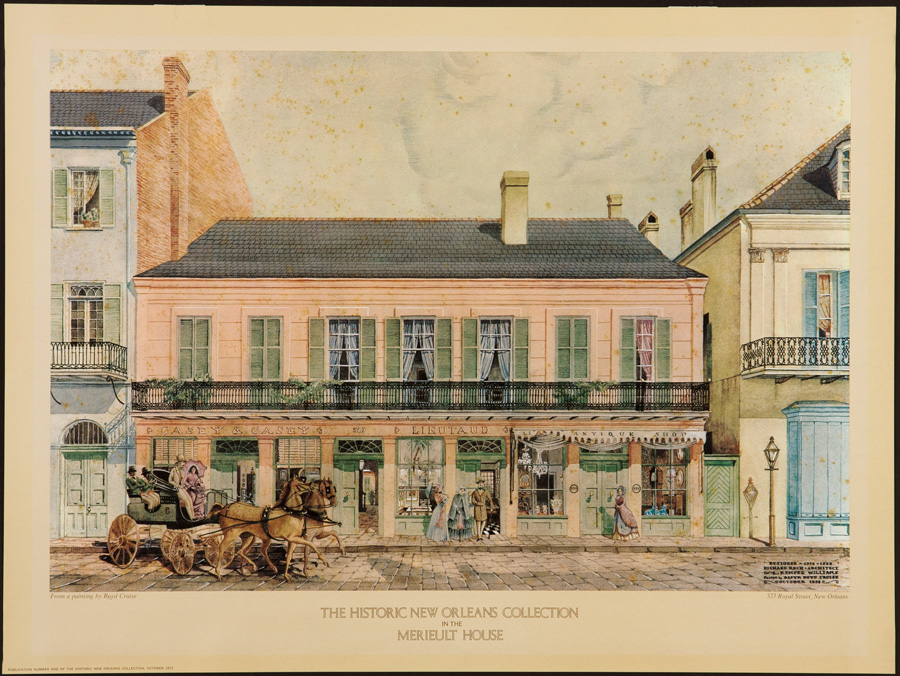

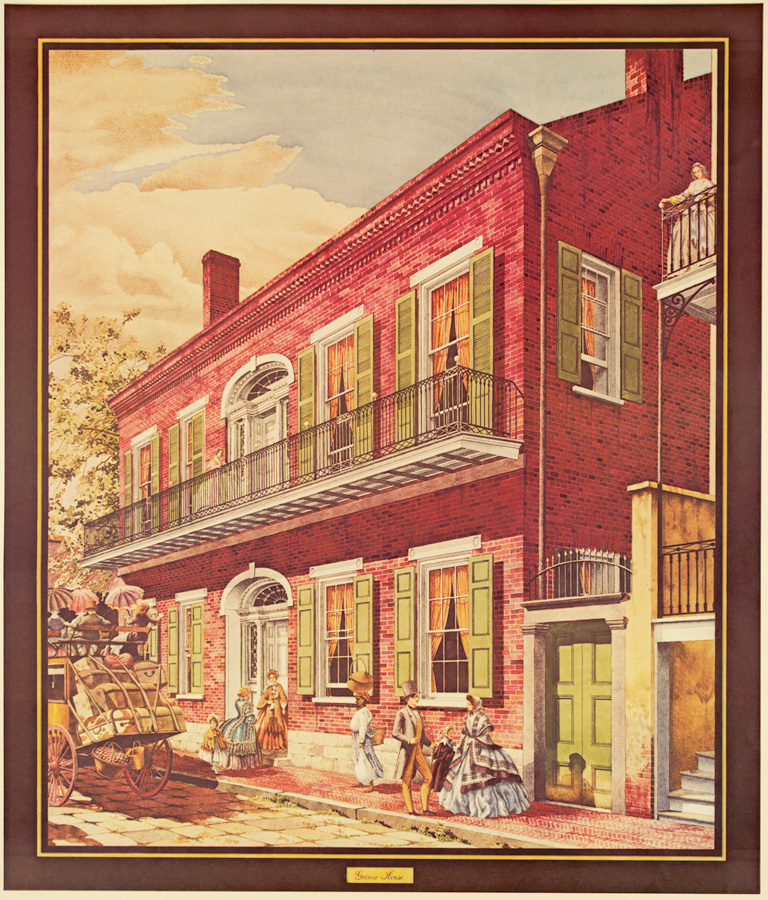

Upon their return to New Orleans following the war, the Williamses completed renovating the Toulouse Street property to use as their personal residence, moving into the house in 1946. Abandoning Uptown for the French Quarter was a radical decision for a couple like Kemper and Leila. At the time, the French Quarter was a bohemian haven, with most of the members of high society (like Kemper and Leila) living Uptown. The Merieult House, built in 1792, was laid out in the Spanish Colonial style, with commercial businesses on the street level and a residence on the upper floor. One of the existing tenants on the ground floor when the Williamses bought the property was Albert Lieutaud (1896 - 1991), who sold art and antiques from his shop. He became an advisor to the Williamses on antiques, as well as a major source of their purchases and acquisitions.

While decorating her French Quarter property, Leila worked with interior designers Marc Antony and Larry Thompson. She was fond of buying European antiques and having them repurposed. One of the many objects that Thompson repurposed for Leila was an early eighteenth- century semi-circular hanging corner cabinet. He created a base for the cabinet, and it eventually became home to a set of Tang Dynasty (618 - 907 CE) funerary figures, which are currently the oldest items in The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Aside from furniture, Leila also collected figurines, pottery, Asian artifacts, paintings, and decorative art objects. One such late eighteenth-century Staffordshire earthenware figurine, depicting a washer woman, was converted into a lamp. The figurine was attached to a wooden base and then wired for electricity.

While Lieutaud was one of Leila's major suppliers, she also shopped at various other French Quarter antique dealers, including the Waldhorn Company and Henry Stern, both located on Royal Street. In fact, Leila's love of antiques encouraged Kemper's collecting, according to the companion catalog for the 1986 THNOC exhibition Kemper and Leila Williams: Collectors/ Founders. Leila thought Kemper needed another focus apart from his business interests. Once he began collecting, Kemper apparently enjoyed the challenge, pursuing only the best and rarest of items.

His early collection efforts focused on visual objects, specifically maps, paintings, and prints. After 1950, he started collecting items related to the culture and history of New Orleans and Louisiana, such as programs, newspapers, magazines, menus, broadsides, music, and business and family papers. Kemper stored the books he collected in his study, and these books eventually became the basis of The Historic New Orleans Collection's research library.

Soon, the Williamses' collection grew so large that they needed help to care for and catalog all of the items. Alvyk Boyd Cruise (1909 - 1988), a gifted artist and watercolorist, was hired one day a week to assist with this task. Cruise had previously worked with Koch on the HABS project, painting pictures of the buildings that Koch was documenting. Cruise eventually became the full-time curator for the Williamses, suspending his painting career to care for their collection. The Williamses also took advantage of the design of their French Quarter property, storing their growing collection on the upper floor of the Merieult House.

As a way to protect and preserve their collection, the Williamses founded the Kemper and Leila Williams Foundation. After Leila passed away on December 13, 1966, her will helped codify and safeguard the collection she and her husband had built. The will made provisions for their Royal Street property to be developed as a museum, with space to store and display the collection, and a requirement to keep the collection open to the public.

After her passing, Kemper continued to add to the collection, striving to create a rich resource for scholars and historians. He also established a five-member board to run the foundation and appointed Cruise to prepare the first displays for The Collection's opening as a public facility in 1970. Cruise also became the first official director of The Collection. General Williams died on November 17, 1971. His will finished the establishment of the endowed institution of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Today, The Historic New Orleans Collection has grown into a living collection of hundreds of thousands of items, with artifacts relating to history and society in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the Gulf South. These items, which are displayed in both rotating and permanent exhibits, as well as in special exhibits in restaurants such as Antoine's and Brennan's, are also available to researchers in the Williams Research Center at 410 Chartres Street. Thousands of people, from filmmakers to students, have benefitted from the generosity, vision, and historical appreciation of the Williamses. What began as a hobby and diversion for the Williamses has blossomed into a premier museum and research institution.

This antique map of America was purchased by General and Mrs. L. Kemper Williams, the founders of The Historic New Orleans Collection, and eventually became the museum's first accessioned item.

Lewis Kemper Williams, known as Kemper, was born September 23, 1887, in Patterson, Louisiana. His parents were cypress magnate Frank B. Williams and Emily Williamson Seyburn. During World War I, he served as a major in the United States Army. Over his lifetime, he also held various positions with Williams Inc., his family's company, ending as Chairman of the Board when he retired in 1971; later in life, he was also named the Honorary Consul of Monaco.

L. Kemper Williams married Leila Hardie Moore on October 2, 1920. Named after her mother, she was born in New Orleans on Lundi Gras, February 19, 1901, to Robert and Leila Hardie Moore. After living for ten years in Patterson, where the main sawmill of the family's lumber business was located, the couple moved to Audubon Street in New Orleans. In 1938, persuaded by architect and preservationist Richard Koch (1889 - 1971), the Williamses bought two properties in the French Quarter to help with revitalization efforts. Both properties - the Merieult House at 533 Royal Street and the adjacent Trapolin House, which fronted Toulouse Street - were in a similar state as the rest of the Vieux Carre - decrepit, and in need of a vast amount of work Koch had worked with the Williamses previously on their Audubon Street home. Koch is perhaps best known today for his work with the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) during the Depression, which documented endangered Louisiana buildings with the hope of restoration and preservation.

With the outbreak of World War II, Kemper resumed his work with the Army, eventually moving to Washington, D.C. with Leila. President Roosevelt named him a brigadier general in 1944.

Upon their return to New Orleans following the war, the Williamses completed renovating the Toulouse Street property to use as their personal residence, moving into the house in 1946. Abandoning Uptown for the French Quarter was a radical decision for a couple like Kemper and Leila. At the time, the French Quarter was a bohemian haven, with most of the members of high society (like Kemper and Leila) living Uptown. The Merieult House, built in 1792, was laid out in the Spanish Colonial style, with commercial businesses on the street level and a residence on the upper floor. One of the existing tenants on the ground floor when the Williamses bought the property was Albert Lieutaud (1896 - 1991), who sold art and antiques from his shop. He became an advisor to the Williamses on antiques, as well as a major source of their purchases and acquisitions.

While decorating her French Quarter property, Leila worked with interior designers Marc Antony and Larry Thompson. She was fond of buying European antiques and having them repurposed. One of the many objects that Thompson repurposed for Leila was an early eighteenth- century semi-circular hanging corner cabinet. He created a base for the cabinet, and it eventually became home to a set of Tang Dynasty (618 - 907 CE) funerary figures, which are currently the oldest items in The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Aside from furniture, Leila also collected figurines, pottery, Asian artifacts, paintings, and decorative art objects. One such late eighteenth-century Staffordshire earthenware figurine, depicting a washer woman, was converted into a lamp. The figurine was attached to a wooden base and then wired for electricity.

While Lieutaud was one of Leila's major suppliers, she also shopped at various other French Quarter antique dealers, including the Waldhorn Company and Henry Stern, both located on Royal Street. In fact, Leila's love of antiques encouraged Kemper's collecting, according to the companion catalog for the 1986 THNOC exhibition Kemper and Leila Williams: Collectors/ Founders. Leila thought Kemper needed another focus apart from his business interests. Once he began collecting, Kemper apparently enjoyed the challenge, pursuing only the best and rarest of items.

His early collection efforts focused on visual objects, specifically maps, paintings, and prints. After 1950, he started collecting items related to the culture and history of New Orleans and Louisiana, such as programs, newspapers, magazines, menus, broadsides, music, and business and family papers. Kemper stored the books he collected in his study, and these books eventually became the basis of The Historic New Orleans Collection's research library.

Soon, the Williamses' collection grew so large that they needed help to care for and catalog all of the items. Alvyk Boyd Cruise (1909 - 1988), a gifted artist and watercolorist, was hired one day a week to assist with this task. Cruise had previously worked with Koch on the HABS project, painting pictures of the buildings that Koch was documenting. Cruise eventually became the full-time curator for the Williamses, suspending his painting career to care for their collection. The Williamses also took advantage of the design of their French Quarter property, storing their growing collection on the upper floor of the Merieult House.

As a way to protect and preserve their collection, the Williamses founded the Kemper and Leila Williams Foundation. After Leila passed away on December 13, 1966, her will helped codify and safeguard the collection she and her husband had built. The will made provisions for their Royal Street property to be developed as a museum, with space to store and display the collection, and a requirement to keep the collection open to the public.

After her passing, Kemper continued to add to the collection, striving to create a rich resource for scholars and historians. He also established a five-member board to run the foundation and appointed Cruise to prepare the first displays for The Collection's opening as a public facility in 1970. Cruise also became the first official director of The Collection. General Williams died on November 17, 1971. His will finished the establishment of the endowed institution of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Today, The Historic New Orleans Collection has grown into a living collection of hundreds of thousands of items, with artifacts relating to history and society in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the Gulf South. These items, which are displayed in both rotating and permanent exhibits, as well as in special exhibits in restaurants such as Antoine's and Brennan's, are also available to researchers in the Williams Research Center at 410 Chartres Street. Thousands of people, from filmmakers to students, have benefitted from the generosity, vision, and historical appreciation of the Williamses. What began as a hobby and diversion for the Williamses has blossomed into a premier museum and research institution.