July 31, 2012

Although many people have heard of the infamous vice district called Storyville, established in 1898 by an act of the New Orleans City Council, few realize that it was not in the French Quarter. Storyville was in fact just outside the French Quarter, in the area bounded by Basin, Customhouse (as Iberville was once called), Robertson and St. Louis Streets. Still, the French Quarter has seen more than its share of prostitution throughout its history - beginning long before the creation of Storyville and continuing long after the district's official closing in 1917.

From the earliest days of colonial New Orleans, the city was plagued with lewd and abandoned women, often sent from the prisons of Paris in a perhaps misguided effort to provide male colonists with wives. In his oft-reprinted 1936 book, The French Quarter: An Informal History of the New Orleans Underworld (Alfred A. Knopf), Herbert Asbury makes the claim that by 1870 there were few blocks in New Orleans, except in the outer fringes of the city, that did not contain at least one brothel or assignation house. This may or may not be true, but there is no doubt that several areas in the French Quarter have a strong historical association with vice, and there are some red-light sites from yesteryear that visitors can see today.

French Market Place, a two-block-long street now occupied by curio and clothing shops, bars and restaurants, was once notorious throughout the country as Gallatin Alley, crowded with riverfront gin mills, bordellos, dance halls and sailors' boarding houses. From about 1840 through the mid-1870s, it operated as the most vicious underworld area in New Orleans, providing a haven for fugitives from the laws of several countries. Thieves, thugs, pimps, drug dealers, drunkards, whores and murderers could be found among its ever-changing population. Passions and tempers ran high in this sordid district, and trivial conflict often produced fatal consequences.

Dance houses typically were two- or three-story buildings with upper floors divided into small rooms, or "cribs," rented on a nightly or weekly basis to women who were not paid by the proprietor; they were expected to make their money by soliciting customers and stealing from them. Most of the women were adept pickpockets and had no qualms about using force against drunken or otherwise incapacitated victims. Among the more noteworthy harlots of Gallatin Alley were Mary Jane "Bricktop" Jackson, said to have killed four men and stabbed numerous others; the brawling America Williams, who stood nearly 6-feet tall; and the violent Delia Swift (alias Bridget Fury), who, like Bricktop, could boast her own string of lethal entanglements.

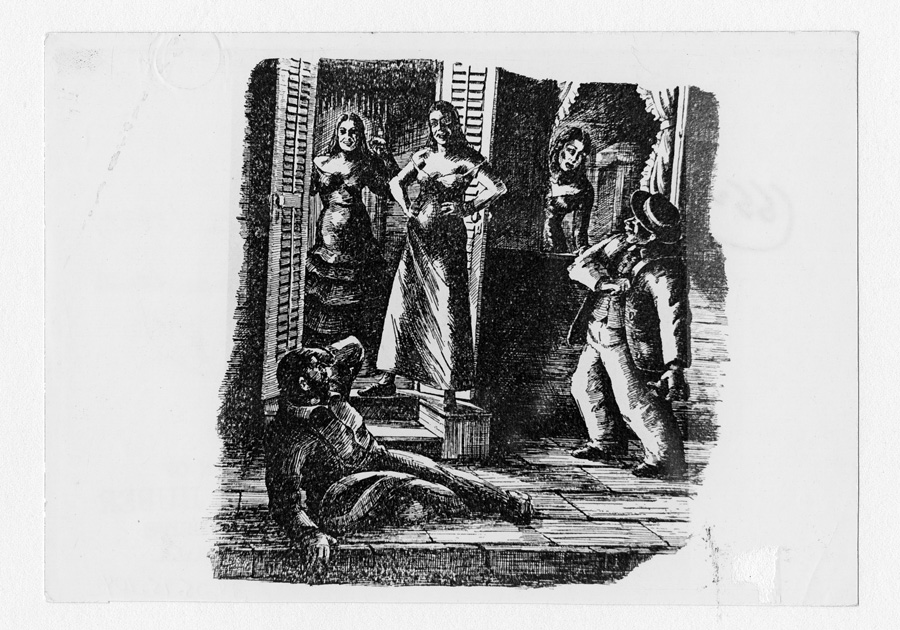

The 300 block of Burgundy, between Bienville and Conti Streets, developed into another area of depraved debauchery during the 1870s and remained so until it was cleared by police in July 1885. Dubbed Smoky Row by the local press, it was mostly inhabited by African American females of all ages in the sex trade, who smoked, chewed tobacco, dipped snuff and drank beer and rot-gut whiskey. A significant portion of their income was made by overcoming potential customers by force, picking them clean and throwing them back into the street. Some of these harridans were known by such colorful names as One-Eye Sal, Gallus Lu and Kidney-Foot Jenny. In the 1910s and early '20s, the area along Burgundy, Dauphine, Iberville and Bienville Streets would see the flowering of dance halls catering to the risque craze of the tango and would become known as the Tango Belt.

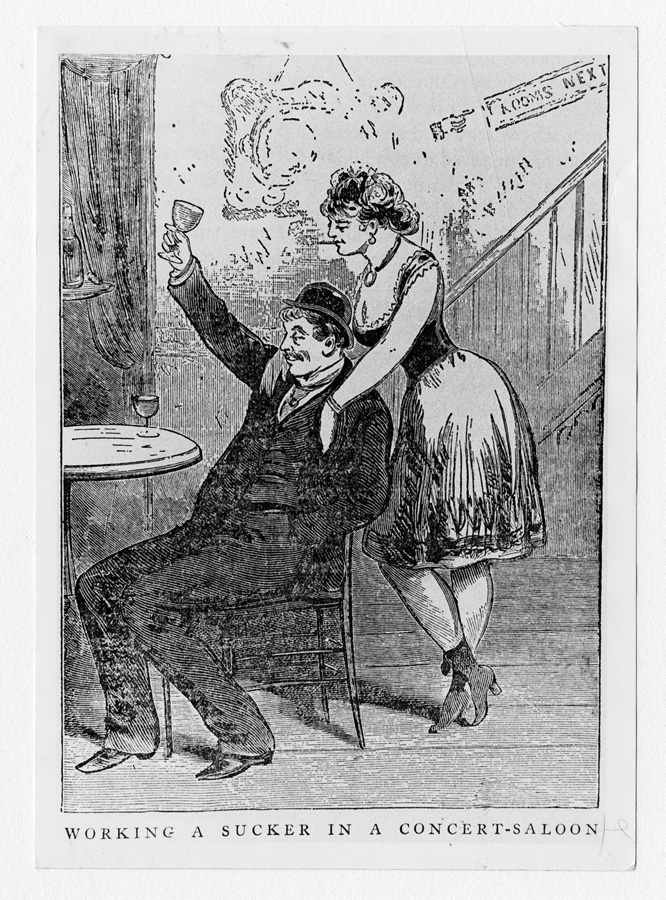

The 1870s and '80s also saw the rise of concert saloons, nearly forgotten today but popular entertainment venues in many American cities in the late 19th century. Often located in prominent shopping and restaurant areas, they were seen as a nuisance by neighboring businessmen. In New Orleans several saloons could be found along Royal and Chartres Streets near Canal, where they offered a dance floor, rowdy musical revues, skits and singers who specialized in bawdy ditties. Elements of the entertainment provided at concert saloons would later form the foundations of burlesque. Food and drink were served by "waiter girls" or "beer jerkers" dressed in brief costumes, who supplemented their tips by turning tricks. One of the many New Orleans concert saloons was the Gem at 127 Royal St. The building still stands, although it is better known as the location of the first meeting of the founding members of the Mistick Krewe of Comus, in 1857.

Several sites in the French Quarter claim to be the location of the House of the Rising Sun, the house that "has been the ruin many a poor boy" in the eponymous song made popular by the Animals in 1964. The Villa Convento, 616 Ursulines St., notes on its website that it is "rumored to be the legendary House of the Rising Sun," and a house at 626 - 28 St. Louis St. has been the subject of similar claims. Even the addition to The Historic New Orleans Collection's Williams Research Center, at 535 - 37 Conti St., was the site of a business called the Rising Sun Hotel in the early 1820s. In his 2007 book, Chasing the Rising Sun: The Journey of an American Song (Simon & Schuster), author Ted Anthony examines the many incarnations of the song, noting that its roots may be traced to the British ballad tradition, predating the foundation of New Orleans by several centuries. He also states that, in nearly every version of the lyrics, the purpose of the house - brothel, prison, gambling den, workhouse - is never actually identified.

Before the establishment of Storyville and the construction of her fabulous Basin Street brothel, Mahogany Hall, Lulu White ran a house at 930 Iberville St., surrounded by several other large brothels, all of which are gone now. For more than 25 years, from 1938 until the mid-1960s, Norma Wallace, the subject of Christine Wiltz's 2000 book, The Last Madam: A Life in the New Orleans Underworld (Faber and Faber), presided over a large bordello at 1026 Conti St. Ironically, it was once the family home of Storyville photographer Ernest J. Bellocq. Symbolic of the ever-changing French Quarter, this former mansion-turned-brothel has been recently renovated into seven lavish apartments.

From the earliest days of colonial New Orleans, the city was plagued with lewd and abandoned women, often sent from the prisons of Paris in a perhaps misguided effort to provide male colonists with wives. In his oft-reprinted 1936 book, The French Quarter: An Informal History of the New Orleans Underworld (Alfred A. Knopf), Herbert Asbury makes the claim that by 1870 there were few blocks in New Orleans, except in the outer fringes of the city, that did not contain at least one brothel or assignation house. This may or may not be true, but there is no doubt that several areas in the French Quarter have a strong historical association with vice, and there are some red-light sites from yesteryear that visitors can see today.

French Market Place, a two-block-long street now occupied by curio and clothing shops, bars and restaurants, was once notorious throughout the country as Gallatin Alley, crowded with riverfront gin mills, bordellos, dance halls and sailors' boarding houses. From about 1840 through the mid-1870s, it operated as the most vicious underworld area in New Orleans, providing a haven for fugitives from the laws of several countries. Thieves, thugs, pimps, drug dealers, drunkards, whores and murderers could be found among its ever-changing population. Passions and tempers ran high in this sordid district, and trivial conflict often produced fatal consequences.

Dance houses typically were two- or three-story buildings with upper floors divided into small rooms, or "cribs," rented on a nightly or weekly basis to women who were not paid by the proprietor; they were expected to make their money by soliciting customers and stealing from them. Most of the women were adept pickpockets and had no qualms about using force against drunken or otherwise incapacitated victims. Among the more noteworthy harlots of Gallatin Alley were Mary Jane "Bricktop" Jackson, said to have killed four men and stabbed numerous others; the brawling America Williams, who stood nearly 6-feet tall; and the violent Delia Swift (alias Bridget Fury), who, like Bricktop, could boast her own string of lethal entanglements.

The 300 block of Burgundy, between Bienville and Conti Streets, developed into another area of depraved debauchery during the 1870s and remained so until it was cleared by police in July 1885. Dubbed Smoky Row by the local press, it was mostly inhabited by African American females of all ages in the sex trade, who smoked, chewed tobacco, dipped snuff and drank beer and rot-gut whiskey. A significant portion of their income was made by overcoming potential customers by force, picking them clean and throwing them back into the street. Some of these harridans were known by such colorful names as One-Eye Sal, Gallus Lu and Kidney-Foot Jenny. In the 1910s and early '20s, the area along Burgundy, Dauphine, Iberville and Bienville Streets would see the flowering of dance halls catering to the risque craze of the tango and would become known as the Tango Belt.

The 1870s and '80s also saw the rise of concert saloons, nearly forgotten today but popular entertainment venues in many American cities in the late 19th century. Often located in prominent shopping and restaurant areas, they were seen as a nuisance by neighboring businessmen. In New Orleans several saloons could be found along Royal and Chartres Streets near Canal, where they offered a dance floor, rowdy musical revues, skits and singers who specialized in bawdy ditties. Elements of the entertainment provided at concert saloons would later form the foundations of burlesque. Food and drink were served by "waiter girls" or "beer jerkers" dressed in brief costumes, who supplemented their tips by turning tricks. One of the many New Orleans concert saloons was the Gem at 127 Royal St. The building still stands, although it is better known as the location of the first meeting of the founding members of the Mistick Krewe of Comus, in 1857.

Several sites in the French Quarter claim to be the location of the House of the Rising Sun, the house that "has been the ruin many a poor boy" in the eponymous song made popular by the Animals in 1964. The Villa Convento, 616 Ursulines St., notes on its website that it is "rumored to be the legendary House of the Rising Sun," and a house at 626 - 28 St. Louis St. has been the subject of similar claims. Even the addition to The Historic New Orleans Collection's Williams Research Center, at 535 - 37 Conti St., was the site of a business called the Rising Sun Hotel in the early 1820s. In his 2007 book, Chasing the Rising Sun: The Journey of an American Song (Simon & Schuster), author Ted Anthony examines the many incarnations of the song, noting that its roots may be traced to the British ballad tradition, predating the foundation of New Orleans by several centuries. He also states that, in nearly every version of the lyrics, the purpose of the house - brothel, prison, gambling den, workhouse - is never actually identified.

Before the establishment of Storyville and the construction of her fabulous Basin Street brothel, Mahogany Hall, Lulu White ran a house at 930 Iberville St., surrounded by several other large brothels, all of which are gone now. For more than 25 years, from 1938 until the mid-1960s, Norma Wallace, the subject of Christine Wiltz's 2000 book, The Last Madam: A Life in the New Orleans Underworld (Faber and Faber), presided over a large bordello at 1026 Conti St. Ironically, it was once the family home of Storyville photographer Ernest J. Bellocq. Symbolic of the ever-changing French Quarter, this former mansion-turned-brothel has been recently renovated into seven lavish apartments.