October 27, 2014

For most Americans, New Year's Day marks the end of the Christmas season. New Orleanians, however, still retain the ancient Christian holiday of Twelfth Night in their holiday calendar, since it not only ends the Christmas season, but begins Carnival season, which lasts until Mardi Gras - Fat Tuesday - a floating holiday which can land anywhere from February 3 to March 9. In 2015 Mardi Gras will be on February 17.

Twelfth Night ends the 12 days of Christmas, a period which starts with Christmas and ends with Epiphany. Eastern Christianity regards this day as the birth of Christ, while in the West it is when the Magi presented gifts to the Christ child. The date of Twelfth Night varies, too, depending upon whether Christmas day is counted, so the English celebrate on January 5, whereas January 6 is the date recognized by the French - and therefore by New Orleanians. Many people in New Orleans still observe Twelfth Night as the time to remove all Christmas decorations, and while families may put their trees on the curb before then, recyclers in the Crescent City do not pick up Christmas trees until after January 6.

Since the Middle Ages, Twelfth Night has been marked with parties, balls and banquets. Eventually, it became such an irreligious, raucous festival that Twelfth Night slipped entirely from the holiday schedule of Protestant England and the North American colonies, but celebrations continued in French Catholic New Orleans. Twelfth Night had once been an occasion for giving lavish gifts, but as the event became more rowdy the chief gift-giving date in France moved to New Year's Day. By the time New Orleans was founded in 1718, Twelfth Night remained the day when Christmas ends and Carnival begins.

A popular Twelfth Night confection in French New Orleans was the gâteau des rois, or kings' cake, a tradition that dates back to the 1300s in Europe. A bean or other small token was baked into the cake, and whoever got the bean when the cake was cut became the party's "lord of misrule." Late 19th-century Twelfth Night parties in New Orleans served such cakes with tokens in much the same manner as in the Middle Ages - although tempered by Victorian propriety. The New Orleans Times in 1870 called these "bean cakes," saying they were more secular than religious and had been long in vogue among Creole families.

These parties were still closely associated with Christmas, and according to the Daily Picayune in 1897, the appropriate colors for Twelfth Night were green and scarlet - traditional colors of Christmas. The newspaper reported that the appropriate decoration for the cake was a small toy Christmas tree and figures of the three kings.

Now king cakes have nothing to do with Christmas and are not the layered cakes of yesteryear. Instead, they are ovals of various sizes; sometimes filled with fruit or crème; decorated with sugar and icing in Carnival colors of purple, green and gold; and beans have been mostly replaced by tiny plastic babies. Now at parties, offices and schools, whoever gets the baby has to buy the next cake. Between Twelfth Night and Mardi Gras, Orleanians' obsession shifts from cheering the Saints to hunting for the best king cake in bakeries from the French Quarter to the suburbs. King cakes are big business, and many are sent to relatives and friends out of town.

Our king cakes are not the only part of the celebration that have evolved. In 1870, Christmas met Carnival when the first parade and ball of the Twelfth Night Revelers happened on January 6th and was heralded as the return of an ancient celebration. The New Orleans Times applauded the occasion, since it revived a holiday that puritanical elements of colonial America had virtually abolished. The Times also praised the economic value of a winter parade as beneficial to the entire community "by throwing a large sum of money into active circulation, a considerable portion of which comes from abroad." The Daily Picayune hailed the Twelfth Night Revelers for formally inaugurating the Carnival season, although the organization's ball invitation was more Christmas card-like with its depiction of holly and ivy.

The parade, with its 16 floats, marched through the American section above Canal Street and into the French Quarter, ending with its ball at the New Opera House (later renamed the French Opera House), at the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse. The opera house was destroyed by fire in 1919, but the cutaway sidewalk on Bourbon in front of the Four Points by Sheraton French Quarter Hotel is a reminder of where carriages once pulled over so that their passengers could alight and enter the theater. The Twelfth Night Revelers only paraded until 1875, but during those years they brought their bright and colorful costumes and lights to the streets of the French Quarter. They still hold an annual ball for their members on Twelfth Night, where the lucky debutante who receives the bean is queen of the ball - but she does not have to give the next party.

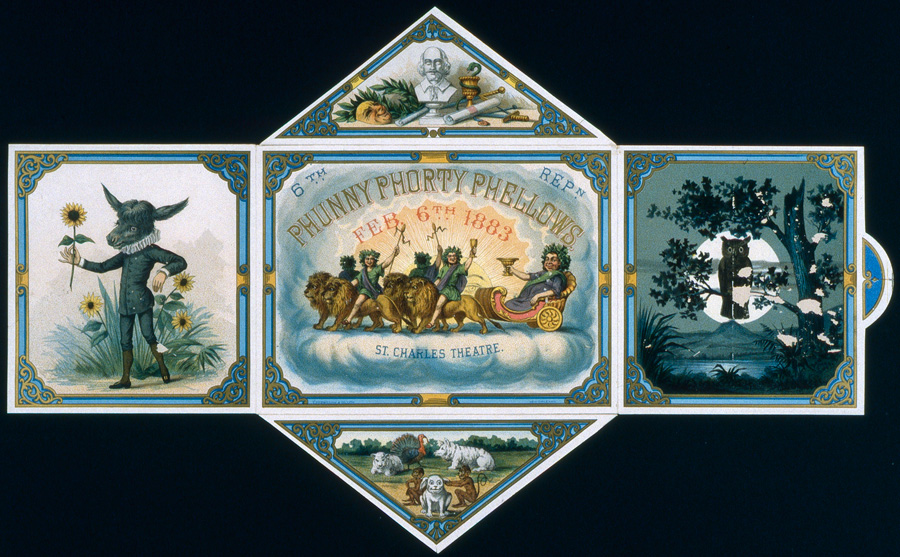

Between 1878 and 1885, and again in 1897and 1898, a group with the silly name of Phunny Phorty Phellows marched after the Rex parade on Mardi Gras. Their slogan was "A little nonsense now and then is relished by the best of men." The group went out of existence, but since 1982 a new set of Phunny Phorty Phellows have welcomed the Carnival season with a Twelfth Night costume party aboard a St. Charles Avenue streetcar that delivers the group to their private ball.

A more public spectacle is The Krewe of Jeanne d'Arc, which has paraded in the French Quarter on Twelfth Night since 2009. Garbed in medieval costumes, the marchers - some on horseback - honor Joan of Arc, the Maid of Orleans and patron saint of France who was burnt at the stake in 1431. A statue of the armor-clad saint stands in the Quarter on the Place de France, a triangle at Decatur and North Peters streets in the French Market. Their 90-minute parade starts at 6:00 p.m., wending its way along Decatur, Conti, Chartres and Ursulines streets. A ceremonial toast is held in front of the the Williams Research Center of The Historic New Orleans Collection on Chartres near Conti, and then the parade passes along Jackson Square and disbands at Washington Artillery Park across from the square on Decatur Street.

Thus the French Quarter and New Orleans usher out the Christmas season. We have no post-New Year's holiday let-down here, since Carnival parades along right afterwards to fill winter's void.

Twelfth Night ends the 12 days of Christmas, a period which starts with Christmas and ends with Epiphany. Eastern Christianity regards this day as the birth of Christ, while in the West it is when the Magi presented gifts to the Christ child. The date of Twelfth Night varies, too, depending upon whether Christmas day is counted, so the English celebrate on January 5, whereas January 6 is the date recognized by the French - and therefore by New Orleanians. Many people in New Orleans still observe Twelfth Night as the time to remove all Christmas decorations, and while families may put their trees on the curb before then, recyclers in the Crescent City do not pick up Christmas trees until after January 6.

Since the Middle Ages, Twelfth Night has been marked with parties, balls and banquets. Eventually, it became such an irreligious, raucous festival that Twelfth Night slipped entirely from the holiday schedule of Protestant England and the North American colonies, but celebrations continued in French Catholic New Orleans. Twelfth Night had once been an occasion for giving lavish gifts, but as the event became more rowdy the chief gift-giving date in France moved to New Year's Day. By the time New Orleans was founded in 1718, Twelfth Night remained the day when Christmas ends and Carnival begins.

A popular Twelfth Night confection in French New Orleans was the gâteau des rois, or kings' cake, a tradition that dates back to the 1300s in Europe. A bean or other small token was baked into the cake, and whoever got the bean when the cake was cut became the party's "lord of misrule." Late 19th-century Twelfth Night parties in New Orleans served such cakes with tokens in much the same manner as in the Middle Ages - although tempered by Victorian propriety. The New Orleans Times in 1870 called these "bean cakes," saying they were more secular than religious and had been long in vogue among Creole families.

These parties were still closely associated with Christmas, and according to the Daily Picayune in 1897, the appropriate colors for Twelfth Night were green and scarlet - traditional colors of Christmas. The newspaper reported that the appropriate decoration for the cake was a small toy Christmas tree and figures of the three kings.

Now king cakes have nothing to do with Christmas and are not the layered cakes of yesteryear. Instead, they are ovals of various sizes; sometimes filled with fruit or crème; decorated with sugar and icing in Carnival colors of purple, green and gold; and beans have been mostly replaced by tiny plastic babies. Now at parties, offices and schools, whoever gets the baby has to buy the next cake. Between Twelfth Night and Mardi Gras, Orleanians' obsession shifts from cheering the Saints to hunting for the best king cake in bakeries from the French Quarter to the suburbs. King cakes are big business, and many are sent to relatives and friends out of town.

Our king cakes are not the only part of the celebration that have evolved. In 1870, Christmas met Carnival when the first parade and ball of the Twelfth Night Revelers happened on January 6th and was heralded as the return of an ancient celebration. The New Orleans Times applauded the occasion, since it revived a holiday that puritanical elements of colonial America had virtually abolished. The Times also praised the economic value of a winter parade as beneficial to the entire community "by throwing a large sum of money into active circulation, a considerable portion of which comes from abroad." The Daily Picayune hailed the Twelfth Night Revelers for formally inaugurating the Carnival season, although the organization's ball invitation was more Christmas card-like with its depiction of holly and ivy.

The parade, with its 16 floats, marched through the American section above Canal Street and into the French Quarter, ending with its ball at the New Opera House (later renamed the French Opera House), at the corner of Bourbon and Toulouse. The opera house was destroyed by fire in 1919, but the cutaway sidewalk on Bourbon in front of the Four Points by Sheraton French Quarter Hotel is a reminder of where carriages once pulled over so that their passengers could alight and enter the theater. The Twelfth Night Revelers only paraded until 1875, but during those years they brought their bright and colorful costumes and lights to the streets of the French Quarter. They still hold an annual ball for their members on Twelfth Night, where the lucky debutante who receives the bean is queen of the ball - but she does not have to give the next party.

Between 1878 and 1885, and again in 1897and 1898, a group with the silly name of Phunny Phorty Phellows marched after the Rex parade on Mardi Gras. Their slogan was "A little nonsense now and then is relished by the best of men." The group went out of existence, but since 1982 a new set of Phunny Phorty Phellows have welcomed the Carnival season with a Twelfth Night costume party aboard a St. Charles Avenue streetcar that delivers the group to their private ball.

A more public spectacle is The Krewe of Jeanne d'Arc, which has paraded in the French Quarter on Twelfth Night since 2009. Garbed in medieval costumes, the marchers - some on horseback - honor Joan of Arc, the Maid of Orleans and patron saint of France who was burnt at the stake in 1431. A statue of the armor-clad saint stands in the Quarter on the Place de France, a triangle at Decatur and North Peters streets in the French Market. Their 90-minute parade starts at 6:00 p.m., wending its way along Decatur, Conti, Chartres and Ursulines streets. A ceremonial toast is held in front of the the Williams Research Center of The Historic New Orleans Collection on Chartres near Conti, and then the parade passes along Jackson Square and disbands at Washington Artillery Park across from the square on Decatur Street.

Thus the French Quarter and New Orleans usher out the Christmas season. We have no post-New Year's holiday let-down here, since Carnival parades along right afterwards to fill winter's void.