January 30, 2013

From its founding in 1718 New Orleans has annually celebrated the Carnival season, beginning on Twelfth Night and ending with Mardi Gras, to usher in the solemnity of Lent, following the Catholic tradition of the city's French founders. Costuming and exchanging roles are ancient parts of European Mardi Gras, and in 18th-century New Orleans, there were already men dressing as women and African slaves impersonating Native Americans. In 1912 the Daily Picayune said some female impersonators "made the fair feminines [sic] themselves feel ashamed ... others ... did so badly that they were laughing stocks."

As New Orleans grew, so did Mardi Gras, and by the 1850s, huge crowds filled the streets - especially in the French Quarter and neighboring business district, where about one-third of the city's nearly 150,000 inhabitants lived. From mansions and tenements alike, masked - and unmasked - revelers poured forth. They frolicked, cheered and drank throughout Mardi Gras, and many reeled home through eerie, gas-lit streets well after midnight, when Ash Wednesday had already descended upon them. By this time, the celebration had become raucous and disreputable, as miscreants tossed flour, dirt and lime at the crowds, causing many people to avoid the celebration, and prompting the press and even city officials to call for the abandonment - even banning - of the rowdy street festivities. In 1854 the French-language New Orleans Bee complained that "Boys with flour paraded the streets, and painted Jezebels exhibited themselves in public carriages .... We are not sorry that this miserable annual exhibition is rapidly becoming extinct. It originated in a barbarous age, and is worthy of only such."

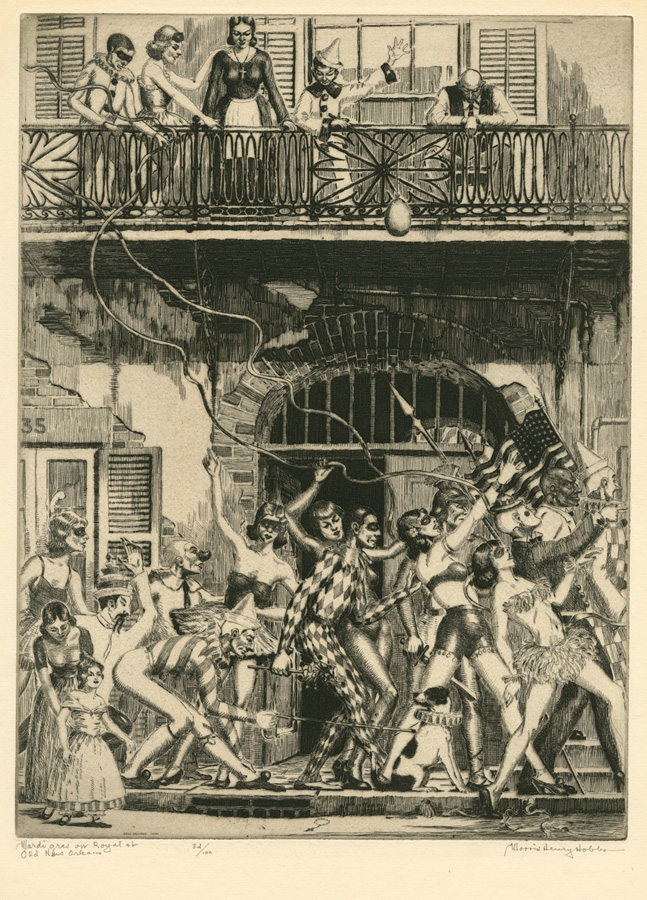

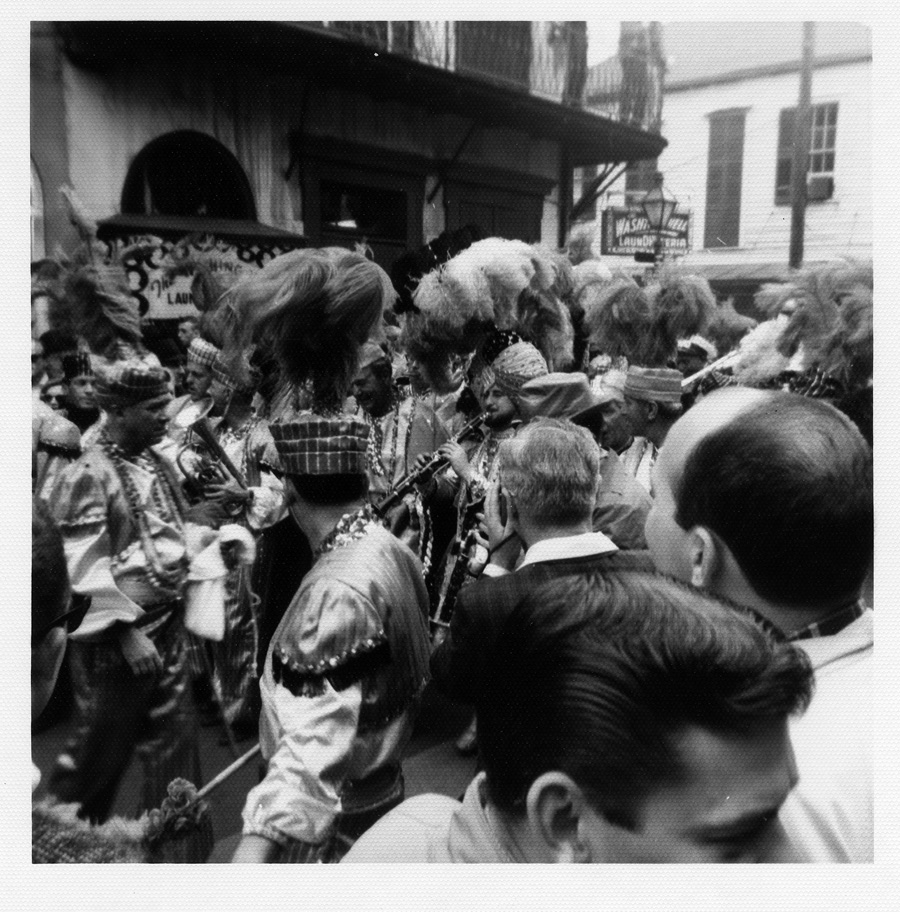

Public Mardi Gras seemed to be on the way out, but the creation of the Mistick Krewe of Comus parade and ball in 1857 by a private men's club gave the celebration new life. The parade was a noisy, torch-lit affair with two floats, bands and several hundred elaborately costumed marchers traversing a few business district streets. Comus took Mardi Gras and the city by storm. It provided magic and spectacle as well as a focus for the end of the public celebration, and it also helped organize unruly crowds. In 1858 Comus returned, much expanded, with a longer route that included Royal, St. Louis and Chartres Streets in the French Quarter. In 1859 the Picayune said, "From noon to night was a display of Mardi Gras maskers not seen in many years .... To a late hour afterward the streets resounded with mirth." Two years later the Picayune reported, "From early in the forenoon there was a continuous scene of fantastic mirth .... Early in the evening banquettes and even the middle of streets were densely packed in expectation of the movement of that mysterious association, the Mistick Krewe of Comus." With the success of Comus, the Carnival season expanded, as krewes following Comus's format were established beginning in the early 1870s.

Masking is a traditional custom of Mardi Gras, but in reality most people in New Orleans do not mask, and in 1912 the Picayune admitted to a preference for a "few maskers with pretty costumes than a million in rags." As opposed to today's casual Carnival attire, at the turn of the last century, people typically went to parades in their Sunday best. Costumed revelers then were referred to as "promiscuous maskers," and in 1912 the Picayune even called them "promiscuous celebrants." "Promiscuous" did not carry today's sexual connotation, but was closer to The Oxford English Dictionary definition - "Consisting of members or elements of different kinds grouped or massed together without order." In New Orleans, save for clubs and parades, masking is an individual choice, and costumes, which may range from elegant to ragtag, are indeed "without order."

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most Mardi Gras celebrants - and this was especially true of the promiscuous maskers - gravitated to Canal Street. Englishman George Augustus Sala in America Revisited (1882) wrote "I would that you were with me in Canal-street .... There was an eruption, a lava-flow, a scoria inundation of masks. Highly-coloured pasteboard will soon be the only facial wear."

Though, as the Picayune wrote in 1912 "at the stroke of 9 the Carnival of 1912 was over and the average Orleanian returned to his home," a more raucous element - many in costume - typically invaded Canal Street as the Comus parade ended. These promiscuous maskers - hollering, blowing horns and roughhousing, linking arms and rushing through the crowds, for example - had critics, but the Picayune said that they "enliven the streets and add to the merriment," and called them "By far the most interesting feature of Mardi Gras .... [Their] antics provide the real fun of the culminating day of the Carnival."

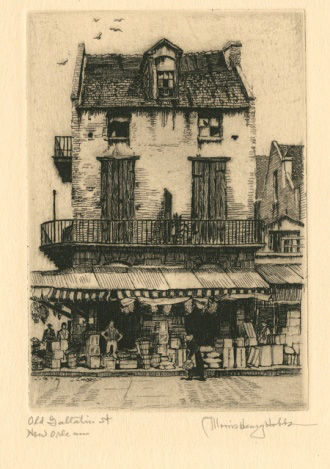

In the early 20th century nighttime revelry began relocating from Canal Street - which was becoming less inviting, with its growing traffic of streetcars and automobiles - to the Tango Belt in the French Quarter. The Tango Belt was centered on Iberville Street between Decatur and Rampart, with an array of taverns, restaurants and dance halls where one could dance the fashionable and risque tango, as well as silly dances named after animals, like the bunny hug, the grizzly bear and the turkey trot - all of which were the rage before World War I.

Prohibition in the 1920s did little to diminish the revelry of Mardi Gras, but massive federal raids in 1925 padlocked French Quarter speakeasies and killed the Tango Belt. With the end of Prohibition in 1933 clubs and bars reopened on nearby Bourbon Street, and during World War II, with the help of visiting servicemen, it began to evolve into the world-famous center of New Orleans nightlife it is today.

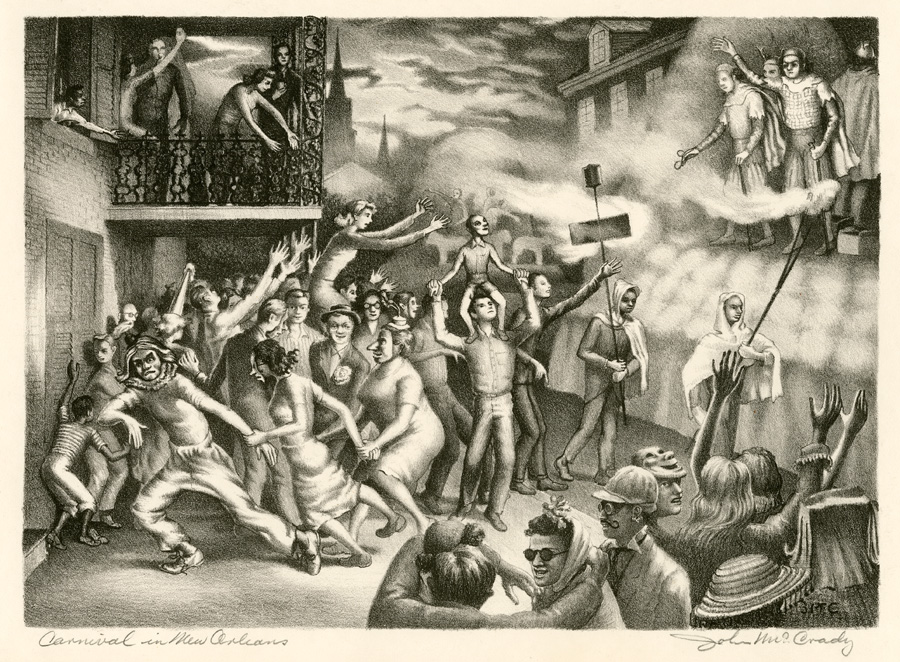

By the '30s, both unmasked and masked revelers - the term "promiscuous maskers" had become passe - began to crowd the streets of the French Quarter more than ever, with Bourbon Street becoming the internationally known epicenter of Mardi Gras festivities. Boisterous crowds have long been part of Mardi Gras activity, and today's shoulder-to-shoulder Bourbon Street crowds are little different from those that once filled Canal Street and then the Tango Belt. A tradition of recent vintage is the parade of mounted police, led by the chief of police, down Bourbon Street at midnight on Mardi Gras, announcing that the party is over and dispersing the crowd as the last official act of the day.

As New Orleans grew, so did Mardi Gras, and by the 1850s, huge crowds filled the streets - especially in the French Quarter and neighboring business district, where about one-third of the city's nearly 150,000 inhabitants lived. From mansions and tenements alike, masked - and unmasked - revelers poured forth. They frolicked, cheered and drank throughout Mardi Gras, and many reeled home through eerie, gas-lit streets well after midnight, when Ash Wednesday had already descended upon them. By this time, the celebration had become raucous and disreputable, as miscreants tossed flour, dirt and lime at the crowds, causing many people to avoid the celebration, and prompting the press and even city officials to call for the abandonment - even banning - of the rowdy street festivities. In 1854 the French-language New Orleans Bee complained that "Boys with flour paraded the streets, and painted Jezebels exhibited themselves in public carriages .... We are not sorry that this miserable annual exhibition is rapidly becoming extinct. It originated in a barbarous age, and is worthy of only such."

Public Mardi Gras seemed to be on the way out, but the creation of the Mistick Krewe of Comus parade and ball in 1857 by a private men's club gave the celebration new life. The parade was a noisy, torch-lit affair with two floats, bands and several hundred elaborately costumed marchers traversing a few business district streets. Comus took Mardi Gras and the city by storm. It provided magic and spectacle as well as a focus for the end of the public celebration, and it also helped organize unruly crowds. In 1858 Comus returned, much expanded, with a longer route that included Royal, St. Louis and Chartres Streets in the French Quarter. In 1859 the Picayune said, "From noon to night was a display of Mardi Gras maskers not seen in many years .... To a late hour afterward the streets resounded with mirth." Two years later the Picayune reported, "From early in the forenoon there was a continuous scene of fantastic mirth .... Early in the evening banquettes and even the middle of streets were densely packed in expectation of the movement of that mysterious association, the Mistick Krewe of Comus." With the success of Comus, the Carnival season expanded, as krewes following Comus's format were established beginning in the early 1870s.

Masking is a traditional custom of Mardi Gras, but in reality most people in New Orleans do not mask, and in 1912 the Picayune admitted to a preference for a "few maskers with pretty costumes than a million in rags." As opposed to today's casual Carnival attire, at the turn of the last century, people typically went to parades in their Sunday best. Costumed revelers then were referred to as "promiscuous maskers," and in 1912 the Picayune even called them "promiscuous celebrants." "Promiscuous" did not carry today's sexual connotation, but was closer to The Oxford English Dictionary definition - "Consisting of members or elements of different kinds grouped or massed together without order." In New Orleans, save for clubs and parades, masking is an individual choice, and costumes, which may range from elegant to ragtag, are indeed "without order."

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most Mardi Gras celebrants - and this was especially true of the promiscuous maskers - gravitated to Canal Street. Englishman George Augustus Sala in America Revisited (1882) wrote "I would that you were with me in Canal-street .... There was an eruption, a lava-flow, a scoria inundation of masks. Highly-coloured pasteboard will soon be the only facial wear."

Though, as the Picayune wrote in 1912 "at the stroke of 9 the Carnival of 1912 was over and the average Orleanian returned to his home," a more raucous element - many in costume - typically invaded Canal Street as the Comus parade ended. These promiscuous maskers - hollering, blowing horns and roughhousing, linking arms and rushing through the crowds, for example - had critics, but the Picayune said that they "enliven the streets and add to the merriment," and called them "By far the most interesting feature of Mardi Gras .... [Their] antics provide the real fun of the culminating day of the Carnival."

In the early 20th century nighttime revelry began relocating from Canal Street - which was becoming less inviting, with its growing traffic of streetcars and automobiles - to the Tango Belt in the French Quarter. The Tango Belt was centered on Iberville Street between Decatur and Rampart, with an array of taverns, restaurants and dance halls where one could dance the fashionable and risque tango, as well as silly dances named after animals, like the bunny hug, the grizzly bear and the turkey trot - all of which were the rage before World War I.

Prohibition in the 1920s did little to diminish the revelry of Mardi Gras, but massive federal raids in 1925 padlocked French Quarter speakeasies and killed the Tango Belt. With the end of Prohibition in 1933 clubs and bars reopened on nearby Bourbon Street, and during World War II, with the help of visiting servicemen, it began to evolve into the world-famous center of New Orleans nightlife it is today.

By the '30s, both unmasked and masked revelers - the term "promiscuous maskers" had become passe - began to crowd the streets of the French Quarter more than ever, with Bourbon Street becoming the internationally known epicenter of Mardi Gras festivities. Boisterous crowds have long been part of Mardi Gras activity, and today's shoulder-to-shoulder Bourbon Street crowds are little different from those that once filled Canal Street and then the Tango Belt. A tradition of recent vintage is the parade of mounted police, led by the chief of police, down Bourbon Street at midnight on Mardi Gras, announcing that the party is over and dispersing the crowd as the last official act of the day.