November 05, 2013

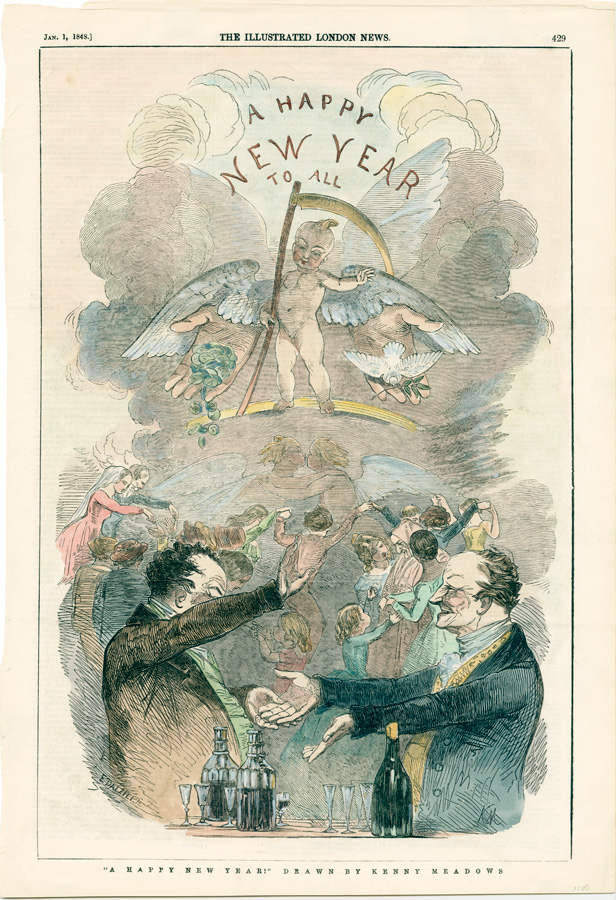

Not until the 18th century was January 1 regarded by most European countries as the start of the New Year. Eventually celebration on this date - or, especially, on New Year's Eve - was not only accepted but marked by convivial gatherings of bounteous good cheer. Boisterous New Year's parties have long been a part of life in New Orleans. Like Christmas and Mardi Gras, the holiday was introduced when the city was a French colony and reinforced later by European immigrants who helped populate the city.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, noise was a hallmark of the entire holiday season in New Orleans. Both Christmas Eve and New Year's Eve brought crowds of revelers streaming into Canal Street and the densely populated French Quarter. Celebrants blew horns, beat drums, and rang bells, shot off fireworks - and even guns - producing a cacophony that grew more earsplitting as Christmas day and New Year's day approached.

Marching bands took to the streets all over town, and in the Quarter the sounds of their blaring horns and pounding drums reverberated off the old brick and plaster buildings. Quarter residents opened their doors, offering holiday drinks and snacks for band members' efforts. Adding more to the New Year's Eve racket, ships' horns were blown at the approach of midnight, a practice that lasted until recent years.

Restaurants, like Antoine's and Galatoire's, along with hotels, like the Monteleone in the Quarter and the St. Charles and Roosevelt in the business district, were packed with revelers wearing paper hats and counting down the minutes and seconds to the New Year.

For the city's large Creole Catholic population the celebration of the New Year was an important and integral part of the Holiday season - and was far more jovial than Christmas with its sacred observances. Creole children received Christmas gifts, but unlike their American counterparts, these were small trinkets, because in France the traditional Christmas gift giver was the Baby Jesus. This meant that big, pricy presents had to wait for the more appropriate and secular New Year's Day.

During this time the Christmas season throughout New Orleans did not start until Christmas Eve and seasonal gift giving lasted right up to New Year. Between the two Holidays shoppers thronged not only Canal Street - then the city's great shopping district - but French Quarter streets like Royal, Chartres and Decatur and the French Market. Newspaper advertisements, especially those in the French-language Bee, promoted both Christmas and New Year's gifts.

Upon receiving their presents on New Year's morning Creole youngsters gave their parents lavish cards the children made themselves of pink paper and lace called complement de jour de l'An which included special affectionate hand written sentiments. Following this was a rich breakfast with foods like grillades (round steak) and grits and lost bread (French toast) - both of which still appear on many New Orleans restaurant menus - along with cakes and other goodies as well as the ever present eggnog - spiked with alcohol for the adults.

New Year's Day was a time to make visits. There were open houses all over New Orleans where family and friends met in parlors where savories, decorated cakes were served along with more eggnog. In the Quarter scores of well dressed Creole families and their children - in many cases wearing outfits that were New Year's gifts - filled the streets making obligatory visits to grandparents and godparents with the prospect of receiving more gifts.

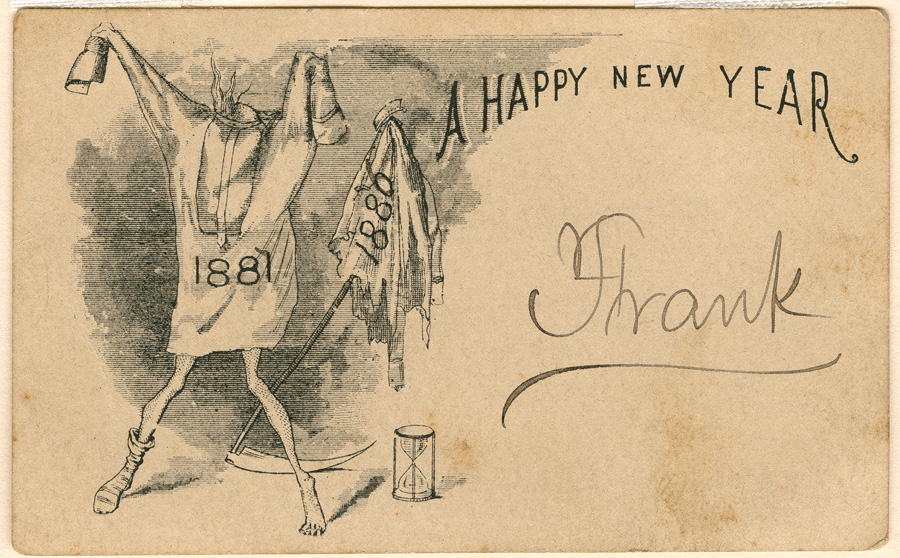

Other children out and about included newspaper boys who worked for city's big dailies like the Picayune, Times- Democrat, States and Item as well as the Bee. They were delivering New Year's carrier's addresses, lavishly illustrated pamphlets containing poetry and good wishes designed to elicit annual money tips from subscribers at a time when these tips were the newsboys' only income. As newspaper companies began paying regular income to delivery boys in the early 20th century, carrier's addresses rapidly went out of vogue.

There were also young men done up in their most fashionable new suits, high starched collars and best hats visiting lady friends. Throughout much of the 19th century, these New Year's Day visits were another obligation of the season. These dandies traveled both on foot and by carriage making as many as several dozen visits to young ladies throughout a busy and tiring day. Each lady - all of whom were dressed in their finest outfits and waiting virtually in state - were given a little decorated cornucopia holding bonbons and dragees - a sugared almond candy - by each man. The women then displayed their caches of gifts to show how many gentleman callers came by. In return the young men were able to partake of light refreshments including boned turkey, cakes, sweets and eggnog - which must have become rather filling after a few visits.

The French reveillon is a late-night meal following an evening event like the theater or opera - and by the late 19th century private at-home reveillons became increasingly popular after Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. Reveillon was also a part of the New Year's celebration - in some homes both New Year's Eve and New Year's Night - but befitting the more secular nature of the New Year these were sumptuous affairs when compared to a Christmas reveillon where only close family were invited and food and drink tended to be light. The New Year's reveillon was indeed the great Creole holiday feast at a time when gargantuan meals were not uncommon. Non-family members were invited to the New Year's reveillon and the event was more jovial - helped along not only by rich food but plentiful drink - and they could last well into the night.

The 20th century brought many changes to New Year's celebrations. Reveillons for instance remain especially popular, but have evolved into something quite different from what they once were. The modern reinterpretation does not take place in a private home, but are fixed price meals in restaurants. Held throughout December, today's reveillons no longer follow a late night event, but are served early in the evening.

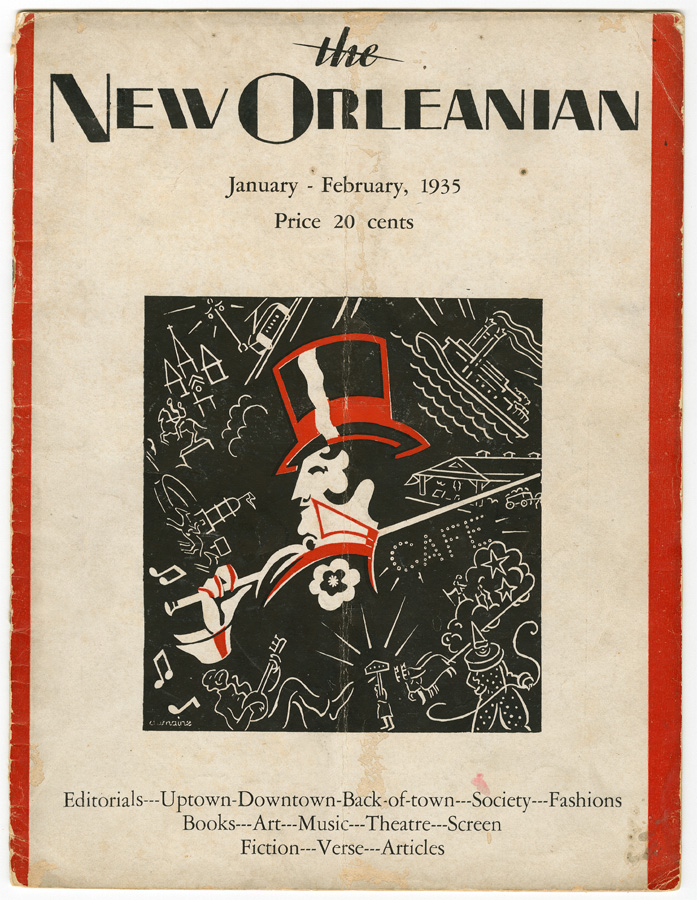

In the early 20th century New Year's Day had become less festive. Many Creole families following the American tradition gave gifts on Christmas. Young men who still visited ladies simply dashed by slipping a calling card in a holder at the front door before this tradition finally died out. Things, however, were enlivened beginning in 1935 with the first Sugar Bowl football game - then held on New Year's Day.

New Year's Eve has long been party central in New Orleans, and today the French Quarter is one of the hottest spots on the globe to ring in the New Year. Since the 1980s revelers have thronged Decatur Street near Jackson Square to count down the arrival of January 1st as a giant fleur-de-lis descends at the top of the JAX Brewery. Nearby on the JAX roof a giant diapered New Year baby grins out at the crowd, while fireworks shot off barges on the Mississippi River illuminate the nighttime sky. After midnight locals and visitors alike crowd the Quarter's narrow streets forcing traffic to slow to a snail's pace.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, noise was a hallmark of the entire holiday season in New Orleans. Both Christmas Eve and New Year's Eve brought crowds of revelers streaming into Canal Street and the densely populated French Quarter. Celebrants blew horns, beat drums, and rang bells, shot off fireworks - and even guns - producing a cacophony that grew more earsplitting as Christmas day and New Year's day approached.

Marching bands took to the streets all over town, and in the Quarter the sounds of their blaring horns and pounding drums reverberated off the old brick and plaster buildings. Quarter residents opened their doors, offering holiday drinks and snacks for band members' efforts. Adding more to the New Year's Eve racket, ships' horns were blown at the approach of midnight, a practice that lasted until recent years.

Restaurants, like Antoine's and Galatoire's, along with hotels, like the Monteleone in the Quarter and the St. Charles and Roosevelt in the business district, were packed with revelers wearing paper hats and counting down the minutes and seconds to the New Year.

For the city's large Creole Catholic population the celebration of the New Year was an important and integral part of the Holiday season - and was far more jovial than Christmas with its sacred observances. Creole children received Christmas gifts, but unlike their American counterparts, these were small trinkets, because in France the traditional Christmas gift giver was the Baby Jesus. This meant that big, pricy presents had to wait for the more appropriate and secular New Year's Day.

During this time the Christmas season throughout New Orleans did not start until Christmas Eve and seasonal gift giving lasted right up to New Year. Between the two Holidays shoppers thronged not only Canal Street - then the city's great shopping district - but French Quarter streets like Royal, Chartres and Decatur and the French Market. Newspaper advertisements, especially those in the French-language Bee, promoted both Christmas and New Year's gifts.

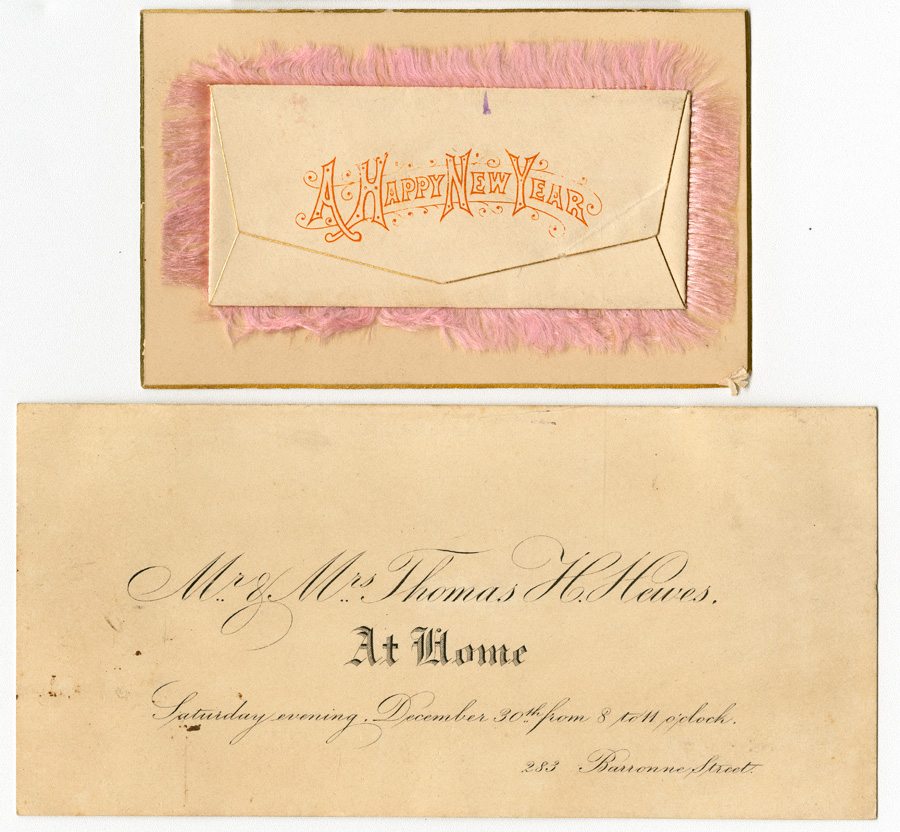

Upon receiving their presents on New Year's morning Creole youngsters gave their parents lavish cards the children made themselves of pink paper and lace called complement de jour de l'An which included special affectionate hand written sentiments. Following this was a rich breakfast with foods like grillades (round steak) and grits and lost bread (French toast) - both of which still appear on many New Orleans restaurant menus - along with cakes and other goodies as well as the ever present eggnog - spiked with alcohol for the adults.

New Year's Day was a time to make visits. There were open houses all over New Orleans where family and friends met in parlors where savories, decorated cakes were served along with more eggnog. In the Quarter scores of well dressed Creole families and their children - in many cases wearing outfits that were New Year's gifts - filled the streets making obligatory visits to grandparents and godparents with the prospect of receiving more gifts.

Other children out and about included newspaper boys who worked for city's big dailies like the Picayune, Times- Democrat, States and Item as well as the Bee. They were delivering New Year's carrier's addresses, lavishly illustrated pamphlets containing poetry and good wishes designed to elicit annual money tips from subscribers at a time when these tips were the newsboys' only income. As newspaper companies began paying regular income to delivery boys in the early 20th century, carrier's addresses rapidly went out of vogue.

There were also young men done up in their most fashionable new suits, high starched collars and best hats visiting lady friends. Throughout much of the 19th century, these New Year's Day visits were another obligation of the season. These dandies traveled both on foot and by carriage making as many as several dozen visits to young ladies throughout a busy and tiring day. Each lady - all of whom were dressed in their finest outfits and waiting virtually in state - were given a little decorated cornucopia holding bonbons and dragees - a sugared almond candy - by each man. The women then displayed their caches of gifts to show how many gentleman callers came by. In return the young men were able to partake of light refreshments including boned turkey, cakes, sweets and eggnog - which must have become rather filling after a few visits.

The French reveillon is a late-night meal following an evening event like the theater or opera - and by the late 19th century private at-home reveillons became increasingly popular after Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. Reveillon was also a part of the New Year's celebration - in some homes both New Year's Eve and New Year's Night - but befitting the more secular nature of the New Year these were sumptuous affairs when compared to a Christmas reveillon where only close family were invited and food and drink tended to be light. The New Year's reveillon was indeed the great Creole holiday feast at a time when gargantuan meals were not uncommon. Non-family members were invited to the New Year's reveillon and the event was more jovial - helped along not only by rich food but plentiful drink - and they could last well into the night.

The 20th century brought many changes to New Year's celebrations. Reveillons for instance remain especially popular, but have evolved into something quite different from what they once were. The modern reinterpretation does not take place in a private home, but are fixed price meals in restaurants. Held throughout December, today's reveillons no longer follow a late night event, but are served early in the evening.

In the early 20th century New Year's Day had become less festive. Many Creole families following the American tradition gave gifts on Christmas. Young men who still visited ladies simply dashed by slipping a calling card in a holder at the front door before this tradition finally died out. Things, however, were enlivened beginning in 1935 with the first Sugar Bowl football game - then held on New Year's Day.

New Year's Eve has long been party central in New Orleans, and today the French Quarter is one of the hottest spots on the globe to ring in the New Year. Since the 1980s revelers have thronged Decatur Street near Jackson Square to count down the arrival of January 1st as a giant fleur-de-lis descends at the top of the JAX Brewery. Nearby on the JAX roof a giant diapered New Year baby grins out at the crowd, while fireworks shot off barges on the Mississippi River illuminate the nighttime sky. After midnight locals and visitors alike crowd the Quarter's narrow streets forcing traffic to slow to a snail's pace.