May 10, 2016

New Orleans, and in particular the Vieux Carré, or the “old square,” as the French Quarter is often referred, is known throughout the world as a destination for gourmands and epicures. As the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray noted, “New Orleans, in spring-time... it seemed to me the city of the world where you can eat and drink the most and suffer the least.” The city is a place to enjoy decadent food of many varieties, but the cuisine that many likely think of when considering New Orleans’s famous food is Creole. Ensuing thoughts might include vague notions of hot spices, okra, and crawfish in dishes such as gumbo, étouffée, and jambalaya, but what does the term really mean? What makes something Creole and what defines Creole cuisine?

The history of how Creole has been used is complicated; it has been used by different people at different times in very different ways. When referring to groups of people at least, it brings up questions of ethnic and racial identity and has been used with both positive and negative connotations. For the purposes of discussing Creole cuisine, however, the broad notion that “Creole” refers to a person born in Louisiana whose ancestors came from somewhere else—whether that is Spain, France, Africa, or the Caribbean—will suffice. It should be noted, however, that one of the main dichotomies implied by using the word Creole in the nineteenth century was to separate “native” New Orleanians from the (generally Anglo) Americans who had started moving to the city following the United States’ purchase of the Louisiana territory. Creoles generally spoke French and lived in the French Quarter, while the Americans spoke English and more often lived in the American Sector, today’s Central Business District. The type of food described by the word Creole, here used as an adjective and not a noun, is somewhat less politically charged, but by no means straightforward, either.

In the most broad possible terms, Creole cuisine is “the cooking of New Orleans and the surrounding areas of southeastern Louisiana” to quote the local food writer and historian Rien Fertel. This is certainly true, and the broad scope of such a statement highlights the difficulty of pinning down the term more precisely. This definition is helpful in distinguishing Creole from Cajun, that other renowned culture with a famous cuisine that originates from Louisiana. Cajuns are the descendants of people from the Acadian region of Canada who emigrated to southwest Louisiana during the eighteenth century.)

Although certainly simplistic, the metaphor of making a gumbo can go a long way to helping describe, if not define, the components of Creole cuisine. The roux is French, the okra African, the filé (an herb made from dried and ground sassafras leaves that acts as a thickening agent as well as flavor) from the native Choctaw, and the peppers Spanish. As the philanthropist and writer Edward Larocque Tinker remarked, “...New Orleans will remain the home of the most sophisticate cookery on this continent—a highly seasoned cuisine with international roots, and indigenous blossoms.”

The natural geography and climate of the land surrounding New Orleans has quite a lot to do with the ingredients that make up Creole cuisine. Particularly in the early colonial days, people incorporated foodstuffs that were readily available with the culinary traditions of the Old World. Both fresh and salt bodies of water are nearby, providing a vast array of seafood, which is indispensable in Creole cooking. Oysters, crabs, shrimp, crawfish, turtles, redfish, snapper, sheepshead, flounder, speckled trout, and more all flourish in the waterways around New Orleans, and all find their ways into dishes served at Creole restaurants throughout the French Quarter. The subtropical climate supports the plentiful vegetation found in local dishes. Tomatoes are essential, as heavy sauces are a customary characteristic of Creole food, as well as garlic, red beans, peppers, rice, sugar, and various other herbs and spices that can be grown locally. Two other ingredients are perhaps more unique: mirlitons, a green gourd shaped like a pear and having a texture somewhere between a cucumber and a potato, and satsumas, a small citrus fruit originally from China.

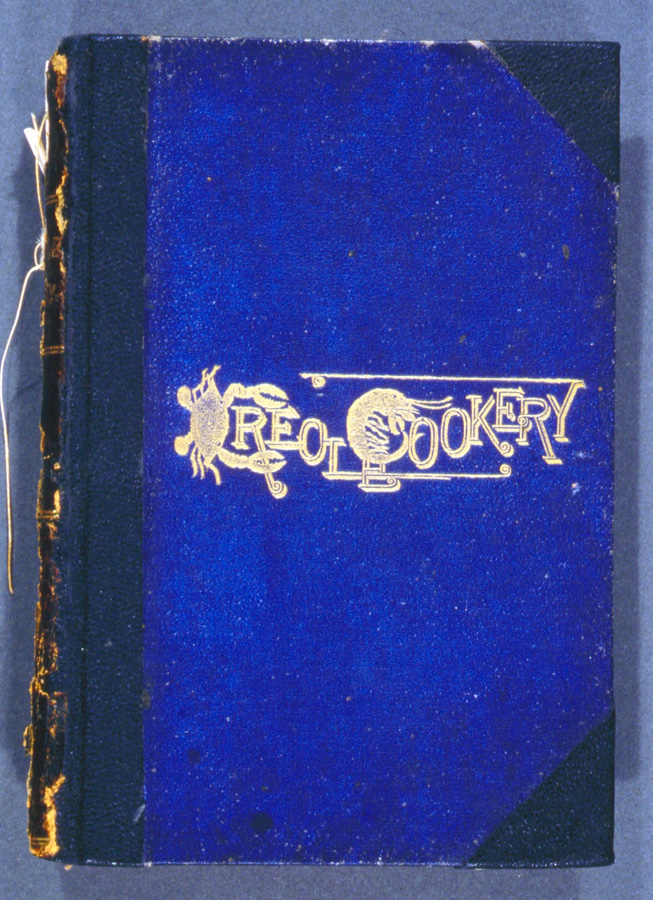

Apart from the ingredients themselves, another important development in the history of Creole cuisine was the codification of its recipes in cookbooks. In 1885 the first Creole cookbooks were published and served as a catalyst for the dispersal of knowledge about the culture and cuisine to the rest of the nation. The first book, La Cuisine Creole: A Collection of Culinary Recipes, From Leading Chefs and Noted Creole Housewives, Who Have Made New Orleans Famous for its Cuisine, was compiled by the noted observer and writer about New Orleans culture Lafcadio Hearn.

Hearn, originally born in Greece, came to New Orleans by way of Ireland and Cincinnati. Mainly working as a newspaper writer, Hearn took an interest in the exotic, the unknown, and the different. New Orleans and its seemingly “foreign” Creole culture appealed to him immediately. He wrote about Voodoo, French opera, Mardi Gras, Creole proverbs, and of course, food. Hearn has been credited as the man who “invented New Orleans,”—it was arguably Hearn who developed, disseminated, and promoted the idea of New Orleans as a different world, a land of mystery and magic, where time passes differently and the normal rules don't apply.

In the same fashion, it was Hearn who helped “invent” the idea of Creole cuisine. The recipes existed, but it was Hearn who collected the culinary traditions of Creole New Orleanians under the heading of “Creole Cuisine.” It became a discrete commodity that could be marketed and sold, and others could begin taking part in this culture. Fittingly, Hearn rushed to publish his cookbook, as well as his book of Creole aphorisms called “Gombo zhèbes”: little dictionary of Creole proverbs, selected from six Creole dialects right before the start of the 1884–85 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans, which was ultimately attracted tourists and visitors from all over the country. Without a doubt, Hearn's vision of Creole cooking has largely shaped the discussion of this topic, even until today.

So finally, what does a Creole meal actually look like when it gets to the table? Well, a hungry visitor can sit down at any number of restaurants in the French Quarter and find out, or acquire any of the numerous cookbooks available, including Hearn’s book. In the meantime, let Edward Larocque Tinker titillate your taste buds with his “most unforgettable gastronomic memory” from Creole City: Its Past and Its People (1953):

“It began with a gombo filé, that succulent soup of myriad and subtle flavors, compounded of oysters, crabs, chicken frames, and a variety of herbs, blended and thickened by filé. Then a huge platter of crawfish tails, spots of toothsome red in a yellow aromatic sauce enriched with mushrooms. This was followed by a fat ‘she-rooster,’ as the Cajuns call a capon, roasted au point. The vegetables were topinambours (Jerusalem artichokes) delicately fried, petits pois bonne femme and aubergines, seasoned by Dora with a masterful hand. A plain green salad au chapon refreshed the palate for desert which was a cake made of ground pecans, brown sugar, and eggs, covered with thick plantation cream. The inevitable demitasse of Louisiana dripped coffee and a thimbleful of 1847 cognac by way of a digestive concluded a meal that was the perfection of Creole cookery.”

The history of how Creole has been used is complicated; it has been used by different people at different times in very different ways. When referring to groups of people at least, it brings up questions of ethnic and racial identity and has been used with both positive and negative connotations. For the purposes of discussing Creole cuisine, however, the broad notion that “Creole” refers to a person born in Louisiana whose ancestors came from somewhere else—whether that is Spain, France, Africa, or the Caribbean—will suffice. It should be noted, however, that one of the main dichotomies implied by using the word Creole in the nineteenth century was to separate “native” New Orleanians from the (generally Anglo) Americans who had started moving to the city following the United States’ purchase of the Louisiana territory. Creoles generally spoke French and lived in the French Quarter, while the Americans spoke English and more often lived in the American Sector, today’s Central Business District. The type of food described by the word Creole, here used as an adjective and not a noun, is somewhat less politically charged, but by no means straightforward, either.

In the most broad possible terms, Creole cuisine is “the cooking of New Orleans and the surrounding areas of southeastern Louisiana” to quote the local food writer and historian Rien Fertel. This is certainly true, and the broad scope of such a statement highlights the difficulty of pinning down the term more precisely. This definition is helpful in distinguishing Creole from Cajun, that other renowned culture with a famous cuisine that originates from Louisiana. Cajuns are the descendants of people from the Acadian region of Canada who emigrated to southwest Louisiana during the eighteenth century.)

Although certainly simplistic, the metaphor of making a gumbo can go a long way to helping describe, if not define, the components of Creole cuisine. The roux is French, the okra African, the filé (an herb made from dried and ground sassafras leaves that acts as a thickening agent as well as flavor) from the native Choctaw, and the peppers Spanish. As the philanthropist and writer Edward Larocque Tinker remarked, “...New Orleans will remain the home of the most sophisticate cookery on this continent—a highly seasoned cuisine with international roots, and indigenous blossoms.”

The natural geography and climate of the land surrounding New Orleans has quite a lot to do with the ingredients that make up Creole cuisine. Particularly in the early colonial days, people incorporated foodstuffs that were readily available with the culinary traditions of the Old World. Both fresh and salt bodies of water are nearby, providing a vast array of seafood, which is indispensable in Creole cooking. Oysters, crabs, shrimp, crawfish, turtles, redfish, snapper, sheepshead, flounder, speckled trout, and more all flourish in the waterways around New Orleans, and all find their ways into dishes served at Creole restaurants throughout the French Quarter. The subtropical climate supports the plentiful vegetation found in local dishes. Tomatoes are essential, as heavy sauces are a customary characteristic of Creole food, as well as garlic, red beans, peppers, rice, sugar, and various other herbs and spices that can be grown locally. Two other ingredients are perhaps more unique: mirlitons, a green gourd shaped like a pear and having a texture somewhere between a cucumber and a potato, and satsumas, a small citrus fruit originally from China.

Apart from the ingredients themselves, another important development in the history of Creole cuisine was the codification of its recipes in cookbooks. In 1885 the first Creole cookbooks were published and served as a catalyst for the dispersal of knowledge about the culture and cuisine to the rest of the nation. The first book, La Cuisine Creole: A Collection of Culinary Recipes, From Leading Chefs and Noted Creole Housewives, Who Have Made New Orleans Famous for its Cuisine, was compiled by the noted observer and writer about New Orleans culture Lafcadio Hearn.

Hearn, originally born in Greece, came to New Orleans by way of Ireland and Cincinnati. Mainly working as a newspaper writer, Hearn took an interest in the exotic, the unknown, and the different. New Orleans and its seemingly “foreign” Creole culture appealed to him immediately. He wrote about Voodoo, French opera, Mardi Gras, Creole proverbs, and of course, food. Hearn has been credited as the man who “invented New Orleans,”—it was arguably Hearn who developed, disseminated, and promoted the idea of New Orleans as a different world, a land of mystery and magic, where time passes differently and the normal rules don't apply.

In the same fashion, it was Hearn who helped “invent” the idea of Creole cuisine. The recipes existed, but it was Hearn who collected the culinary traditions of Creole New Orleanians under the heading of “Creole Cuisine.” It became a discrete commodity that could be marketed and sold, and others could begin taking part in this culture. Fittingly, Hearn rushed to publish his cookbook, as well as his book of Creole aphorisms called “Gombo zhèbes”: little dictionary of Creole proverbs, selected from six Creole dialects right before the start of the 1884–85 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans, which was ultimately attracted tourists and visitors from all over the country. Without a doubt, Hearn's vision of Creole cooking has largely shaped the discussion of this topic, even until today.

So finally, what does a Creole meal actually look like when it gets to the table? Well, a hungry visitor can sit down at any number of restaurants in the French Quarter and find out, or acquire any of the numerous cookbooks available, including Hearn’s book. In the meantime, let Edward Larocque Tinker titillate your taste buds with his “most unforgettable gastronomic memory” from Creole City: Its Past and Its People (1953):

“It began with a gombo filé, that succulent soup of myriad and subtle flavors, compounded of oysters, crabs, chicken frames, and a variety of herbs, blended and thickened by filé. Then a huge platter of crawfish tails, spots of toothsome red in a yellow aromatic sauce enriched with mushrooms. This was followed by a fat ‘she-rooster,’ as the Cajuns call a capon, roasted au point. The vegetables were topinambours (Jerusalem artichokes) delicately fried, petits pois bonne femme and aubergines, seasoned by Dora with a masterful hand. A plain green salad au chapon refreshed the palate for desert which was a cake made of ground pecans, brown sugar, and eggs, covered with thick plantation cream. The inevitable demitasse of Louisiana dripped coffee and a thimbleful of 1847 cognac by way of a digestive concluded a meal that was the perfection of Creole cookery.”