January 29, 2020

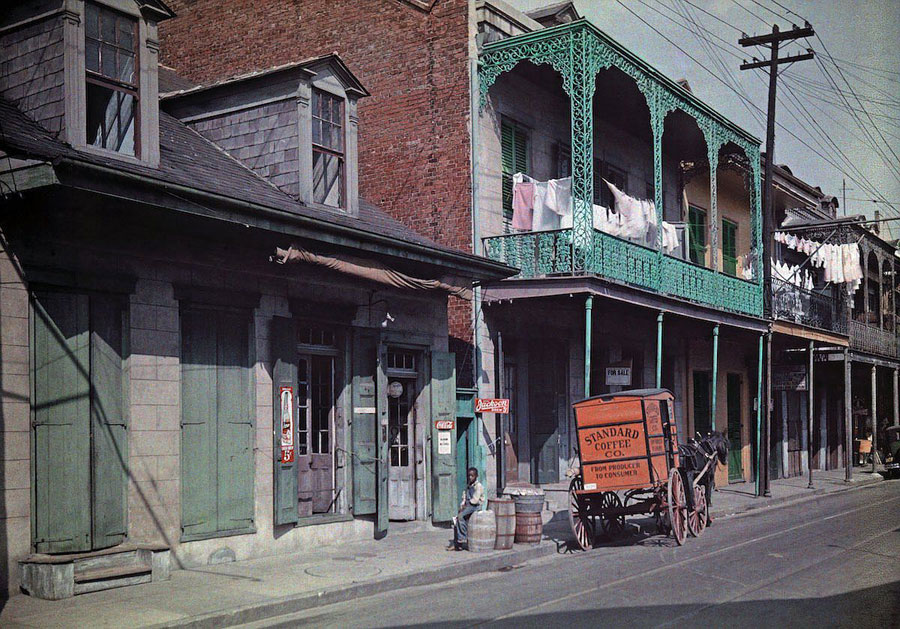

Take a look around at your surroundings in the French Quarter and try to imagine what it was like one hundred years ago. In the Roaring Twenties, the neighborhood attracted artists and writers with its low-rent, faded charm, and colorful street life. Jackson Square was the center of a vibrant yet short-lived bohemia. The Quarter was mostly a gritty working class slum where people spoke French as often as English. Women lowered baskets to the street to grocers who loaded them with food and added a pint of gin. Artists and writers had taken to the area, seduced by its cheap rent. Oliver Lafarge wrote his Pulitzer Prize-winning Laughing Boy there; Faulkner wrote Soldiers’ Pay, encouraged by Sherwood Anderson, who entertained visitors like Theodore Dreiser, Alice B. Toklas, Gertrude Stein, and Bertrand Russell. One of Anderson's friends even wrote a book about Paris without ever having visited it, instead using New Orleans as his model; Parisians read it, Anderson reported, with "delight." The smells of the docks hung over the whole area, from rotting bananas from the United Fruit Company, the single largest user of the port, to the sweet smell of the dozens of bakeries making bread. The finest restaurants, Antoine's, Galatoire's, Arnaud's, and Broussard's, were there, and so were working class cafés. In Jackson Square at Billy Cabildo's, fifty cents yielded an enormous bowl of homemade soup, boiled beef, an entree, dessert, and coffee. The square itself was surrounded by hedges where prostitutes took clients. Working class whites lived downriver and made their living from the port, sugar and timber mills, and slaughterhouses.

The social elite lived upriver on St. Charles Avenue and in the Garden District. Only recently, jazz had been born from deep in the bowels of the city, its beat emerging from the African jungle into Congo Square, then spreading to the whorehouses of Storyville, where Jelly Roll Morton and the Spasm band, possibly the original jazz combination, and a little later Louis Armstrong played. At its peak, Storyville had two newspapers and its own Carnival ball; the best houses even had advertising brochures!

During this time, the Quarter’s nightlife evolved. It attracted many locals and visitors to its world-renowned night life. In the early 1900s, the “Tango Belt” around Iberville Street had an array of dance halls, bars, restaurants and theaters. Prohibition in 1920 destroyed the Tango Belt, but at the same time a few clubs began turning Bourbon Street into a nightlife venue. By the end of Prohibition in 1933, Bourbon Street nightlife was replacing the Tango Belt, becoming one of the most fabled streets in the world.

English bankers began living full-time in New Orleans in the 1800s. As a result, before the Civil War, New Orleans was the wealthiest per capita city in America. In the 1920s, it remained by far the wealthiest city in the South. Its Cotton Exchange was one of the three most important in the world. Its port was second only to New York. Its banks were the largest and most important in the South. According to a Federal Reserve study, New Orleans had nearly twice the economic activity of Dallas, the South's second-wealthiest city. The Quarter started filling with artists, writers, nonconformists, and gays seeking refuge among the Quarter's permissive denizens. The several blocks around William Faulkner's apartment on Pirate's Alley presented a cultural and social scene not unlike that of New York's Greenwich Village. New Orleans's eccentricity and the presence of so many artistic and literary luminaries proved mutually beneficial. Bohemians realized the importance of saving French Quarter architecture, leading to the creation of the nation's first city-level historic preservation agency, the Vieux Carré Commission, in 1925. Heritage-minded newcomers restored dozens of French Quarter properties as homes.

In 1919, the Old Absinthe House was an iconic establishment. Prohibition caused major changes in culture across the nation, but it wasn’t the only upheaval in Crescent City nightlife. At the end of 1917, the Navy forced the city to close Storyville, the 38-block district just a five-minute walk from the Absinthe House where prostitution was practiced openly and legally. Of course, as Mayor Martin Behrman said at the time, “you can make it illegal, but you can’t make it unpopular.” The closing of Storyville forced the prostitutes, madams, bartenders, bouncers, and musicians into the surrounding blocks.

As Richard Campanella points out in his 2014 book, Bourbon Street: A History, an entertainment street was evolving with a German beer garden, a few restaurants, and a couple other bars. Before Prohibition, Bourbon Street had been fairly quiet; in 1919, the Absinthe House was about the rowdiest thing on it, not counting the old French Opera House which burned down in that year, only months after Prohibition took hold. Bourbon Street began filling up with decidedly wet cabarets and dance clubs of the kind previously confined to Storyville. Meanwhile, quiet side streets between Bourbon and Basin St., where Storyville had begun, started filling up with bogus “hotels” and “rooming houses” where the fishers of men could bring their catches.

Prohibition descended on a deeply divided land, where half the people were grumbling and half were satisfied. As one would expect, New Orleans was in the grumbling half. In fact, Prohibition really threw the city for a loop. A quarter of a century before, it had transformed itself from a commercial port city into a tourist mecca, on the basis of good food, good times and good drinks. Without the drinks, the rest of the package was in danger.

In the 1920s, a bohemian scene emerged in the French Quarter that the Double Dealer magazine hailed in 1922 as “The Renaissance of the Vieux Carré.” The French Quarter evolved from a slum into a tourist destination and a fashionable residential center. Anthropologist and novelist Oliver La Farge described the French Quarter of the 1920s as “a decaying monument and a slum as rich as jambalaya or gumbo.” Most of its elegant buildings had been divided into tenements rented to the poor, notably Sicilian immigrants who made up eighty percent of the resident population in 1910. Artists and writers began to move into the area attracted by the cheap rent, faded charm, and colorful street life. The positive developments from the French Quarter renaissance of the 1920s attracted attention and visitors, inspiring the historic preservation and commercial revitalization that turned the area into a tourist destination. Predictably, this gentrification drove out many of the working artists and writers who had helped revive the area. Their dazzling world faded as quickly as it began.

Many business people saw the French Quarter’s commercial potential. The first practical proposal for large-scale renovation came from the president of the Association of Commerce. In 1919, he suggested that the Pontalba buildings flanking Jackson Square should be converted to studios and living spaces for artists.

One of the Quarter’s best-known figures was William Spratling, a young artist and jewelry designer on the architecture faculty at Tulane. Spratling and William Faulkner shared a home at 624 Pirate’s Alley, which is now a charming bookstore. Together, they self-published a slim book in 1926 entitled Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles, which Spratling described later as, “a sort of mirror of our scene in New Orleans.” Comprised simply of Spratling’s drawings of their friends and an introduction by Faulkner, the book gives an idea of the sort of creative figures involved in the Renaissance. When you stroll through the streets of the French Quarter, you are walking in the footsteps of many famous American and European authors. Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, Tennessee Williams, Washington Irving, and Carl Sandberg are among the myriad major literary figures who have frequented or lived here. These people helped to establish New Orleans institutions such as the Double Dealer literary magazine, the Arts and Crafts Club, and Le Petit Theatre.

The Quarter also offered cafés for midday coffee and conversation, inexpensive Creole and Italian restaurants, and an abundance of Prohibition-era speakeasies. At one point, seventy-four speakeasies lined a nine-block radius! Le Petit Theatre provided a setting where high society could mingle with bohemians. Many of the Quarter’s artists, writers, and musicians were involved in production and design.

Some Uptown visitors liked it so much that they purchased houses as rental property while the more adventurous moved into the Quarter themselves. Many of them would later be called “fauxhemians who rent an ordinary furnished room and call it [their] studio.” In 1922, The New York Times observed that, “the French Quarter has become a fad. It has become, in a way, fashionable.”

Inevitably, the Quarter’s new appeal was soon reflected in rising rent and real estate. In 1925, when Natalie Scott sold a St. Peter Street apartment property she had owned for only sixteen months, she tripled her investment. The days when Lyle Saxon could rent a sixteen-room house on Royal Street for sixteen dollars a month would not come again. Increasing rent meant fewer artists and writers could afford to live in the Quarter, and the influx of tourists and businesses catering to them meant that fewer creative types wanted to live in a neighborhood that was becoming increasingly commercialized. By the 1930s, Faulkner went home to Mississippi, the Andersons left for Virginia, while others went to New York, Paris, Mexico and Santa Fe. Our bohemian moment had passed.

Once home to large extended families living in tenements, the more gentrified French Quarter of today is composed mostly of single-family, duplexes, and condominium residential units. With few apartment buildings, the Quarter’s population has declined from about 20,000 residents in the 1920s to about 4,000 residents now. They graciously accept over 15 million tourists annually in their neighborhood which occupies the same six by thirteen block grid laid out in 1722 as the original city of New Orleans. It is one of the oldest residential communities in America and was named a National Historic Landmark in 1966. The National Trust for Historic Preservation considers the French Quarter to be one of the most endangered historical places in the country. Vive la Vieux Carré!

The social elite lived upriver on St. Charles Avenue and in the Garden District. Only recently, jazz had been born from deep in the bowels of the city, its beat emerging from the African jungle into Congo Square, then spreading to the whorehouses of Storyville, where Jelly Roll Morton and the Spasm band, possibly the original jazz combination, and a little later Louis Armstrong played. At its peak, Storyville had two newspapers and its own Carnival ball; the best houses even had advertising brochures!

During this time, the Quarter’s nightlife evolved. It attracted many locals and visitors to its world-renowned night life. In the early 1900s, the “Tango Belt” around Iberville Street had an array of dance halls, bars, restaurants and theaters. Prohibition in 1920 destroyed the Tango Belt, but at the same time a few clubs began turning Bourbon Street into a nightlife venue. By the end of Prohibition in 1933, Bourbon Street nightlife was replacing the Tango Belt, becoming one of the most fabled streets in the world.

English bankers began living full-time in New Orleans in the 1800s. As a result, before the Civil War, New Orleans was the wealthiest per capita city in America. In the 1920s, it remained by far the wealthiest city in the South. Its Cotton Exchange was one of the three most important in the world. Its port was second only to New York. Its banks were the largest and most important in the South. According to a Federal Reserve study, New Orleans had nearly twice the economic activity of Dallas, the South's second-wealthiest city. The Quarter started filling with artists, writers, nonconformists, and gays seeking refuge among the Quarter's permissive denizens. The several blocks around William Faulkner's apartment on Pirate's Alley presented a cultural and social scene not unlike that of New York's Greenwich Village. New Orleans's eccentricity and the presence of so many artistic and literary luminaries proved mutually beneficial. Bohemians realized the importance of saving French Quarter architecture, leading to the creation of the nation's first city-level historic preservation agency, the Vieux Carré Commission, in 1925. Heritage-minded newcomers restored dozens of French Quarter properties as homes.

In 1919, the Old Absinthe House was an iconic establishment. Prohibition caused major changes in culture across the nation, but it wasn’t the only upheaval in Crescent City nightlife. At the end of 1917, the Navy forced the city to close Storyville, the 38-block district just a five-minute walk from the Absinthe House where prostitution was practiced openly and legally. Of course, as Mayor Martin Behrman said at the time, “you can make it illegal, but you can’t make it unpopular.” The closing of Storyville forced the prostitutes, madams, bartenders, bouncers, and musicians into the surrounding blocks.

As Richard Campanella points out in his 2014 book, Bourbon Street: A History, an entertainment street was evolving with a German beer garden, a few restaurants, and a couple other bars. Before Prohibition, Bourbon Street had been fairly quiet; in 1919, the Absinthe House was about the rowdiest thing on it, not counting the old French Opera House which burned down in that year, only months after Prohibition took hold. Bourbon Street began filling up with decidedly wet cabarets and dance clubs of the kind previously confined to Storyville. Meanwhile, quiet side streets between Bourbon and Basin St., where Storyville had begun, started filling up with bogus “hotels” and “rooming houses” where the fishers of men could bring their catches.

Prohibition descended on a deeply divided land, where half the people were grumbling and half were satisfied. As one would expect, New Orleans was in the grumbling half. In fact, Prohibition really threw the city for a loop. A quarter of a century before, it had transformed itself from a commercial port city into a tourist mecca, on the basis of good food, good times and good drinks. Without the drinks, the rest of the package was in danger.

In the 1920s, a bohemian scene emerged in the French Quarter that the Double Dealer magazine hailed in 1922 as “The Renaissance of the Vieux Carré.” The French Quarter evolved from a slum into a tourist destination and a fashionable residential center. Anthropologist and novelist Oliver La Farge described the French Quarter of the 1920s as “a decaying monument and a slum as rich as jambalaya or gumbo.” Most of its elegant buildings had been divided into tenements rented to the poor, notably Sicilian immigrants who made up eighty percent of the resident population in 1910. Artists and writers began to move into the area attracted by the cheap rent, faded charm, and colorful street life. The positive developments from the French Quarter renaissance of the 1920s attracted attention and visitors, inspiring the historic preservation and commercial revitalization that turned the area into a tourist destination. Predictably, this gentrification drove out many of the working artists and writers who had helped revive the area. Their dazzling world faded as quickly as it began.

Many business people saw the French Quarter’s commercial potential. The first practical proposal for large-scale renovation came from the president of the Association of Commerce. In 1919, he suggested that the Pontalba buildings flanking Jackson Square should be converted to studios and living spaces for artists.

One of the Quarter’s best-known figures was William Spratling, a young artist and jewelry designer on the architecture faculty at Tulane. Spratling and William Faulkner shared a home at 624 Pirate’s Alley, which is now a charming bookstore. Together, they self-published a slim book in 1926 entitled Sherwood Anderson and Other Famous Creoles, which Spratling described later as, “a sort of mirror of our scene in New Orleans.” Comprised simply of Spratling’s drawings of their friends and an introduction by Faulkner, the book gives an idea of the sort of creative figures involved in the Renaissance. When you stroll through the streets of the French Quarter, you are walking in the footsteps of many famous American and European authors. Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, Tennessee Williams, Washington Irving, and Carl Sandberg are among the myriad major literary figures who have frequented or lived here. These people helped to establish New Orleans institutions such as the Double Dealer literary magazine, the Arts and Crafts Club, and Le Petit Theatre.

The Quarter also offered cafés for midday coffee and conversation, inexpensive Creole and Italian restaurants, and an abundance of Prohibition-era speakeasies. At one point, seventy-four speakeasies lined a nine-block radius! Le Petit Theatre provided a setting where high society could mingle with bohemians. Many of the Quarter’s artists, writers, and musicians were involved in production and design.

Some Uptown visitors liked it so much that they purchased houses as rental property while the more adventurous moved into the Quarter themselves. Many of them would later be called “fauxhemians who rent an ordinary furnished room and call it [their] studio.” In 1922, The New York Times observed that, “the French Quarter has become a fad. It has become, in a way, fashionable.”

Inevitably, the Quarter’s new appeal was soon reflected in rising rent and real estate. In 1925, when Natalie Scott sold a St. Peter Street apartment property she had owned for only sixteen months, she tripled her investment. The days when Lyle Saxon could rent a sixteen-room house on Royal Street for sixteen dollars a month would not come again. Increasing rent meant fewer artists and writers could afford to live in the Quarter, and the influx of tourists and businesses catering to them meant that fewer creative types wanted to live in a neighborhood that was becoming increasingly commercialized. By the 1930s, Faulkner went home to Mississippi, the Andersons left for Virginia, while others went to New York, Paris, Mexico and Santa Fe. Our bohemian moment had passed.

Once home to large extended families living in tenements, the more gentrified French Quarter of today is composed mostly of single-family, duplexes, and condominium residential units. With few apartment buildings, the Quarter’s population has declined from about 20,000 residents in the 1920s to about 4,000 residents now. They graciously accept over 15 million tourists annually in their neighborhood which occupies the same six by thirteen block grid laid out in 1722 as the original city of New Orleans. It is one of the oldest residential communities in America and was named a National Historic Landmark in 1966. The National Trust for Historic Preservation considers the French Quarter to be one of the most endangered historical places in the country. Vive la Vieux Carré!