February 03, 2016

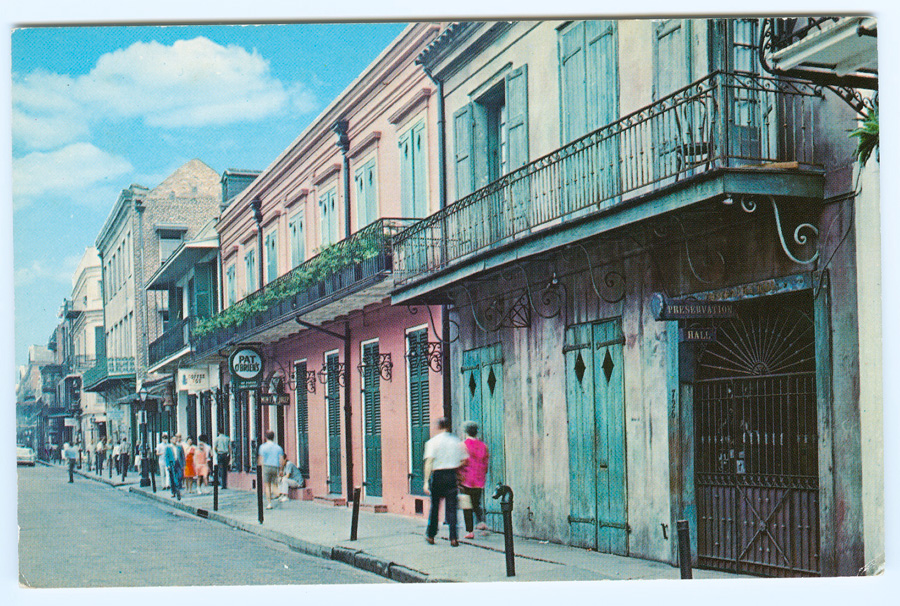

Of all the things people associate with the French Quarter—food, history, architecture, cocktails...and on and on—music (like the Saints) has to be included in that number. Whether it is the sound of a brass band blasting out an old standard for the tourists around Jackson Square, the rhythm of a funk band covering classic-rock songs over on Bourbon Street, or the dueling pianos battling all night long at Pat O’Brien’s, music is ubiquitous in the Vieux Carré. New Orleans has long been hailed as one of the music capitals of the United States, but there was a time, during the middle part of the twentieth century, when the musical legacy of the French Quarter was firmly codified and preserved. In some ways, this period was responsible for the current elevated status of music in the city today.

Jazz music was nurtured, if not born (that is a debate for another time), in the streets, bars, and nightclubs of New Orleans in the early part of the twentieth century. It was in and around Storyville, the notorious red-light district of New Orleans adjacent to the Quarter, that many of the early New Orleans jazz bands got their starts. However, a variety of factors, including the closure of Storyville in 1917, the onset of the Great Depression, and the increasing popularity of other styles of jazz in places like Chicago and New York, led to an erosion of interest in the New Orleans style of traditional jazz music. By the late 1930s many of the original New Orleans jazz musicians—at least the ones who hadn’t already left New Orleans for greener pastures—were aging and living in obscurity, sometimes even poverty. The publication of Jazzmen: The Story of Hot Jazz Told in the Lives of the Men Who Created It, edited by Frederic Ramsey and Charles Edward Smith, in 1939, helped bring the early history of jazz, and particularly the importance of New Orleans in that story, to a wider national audience. Significantly, a young jazz aficionado named Bill Russell contributed to that book.

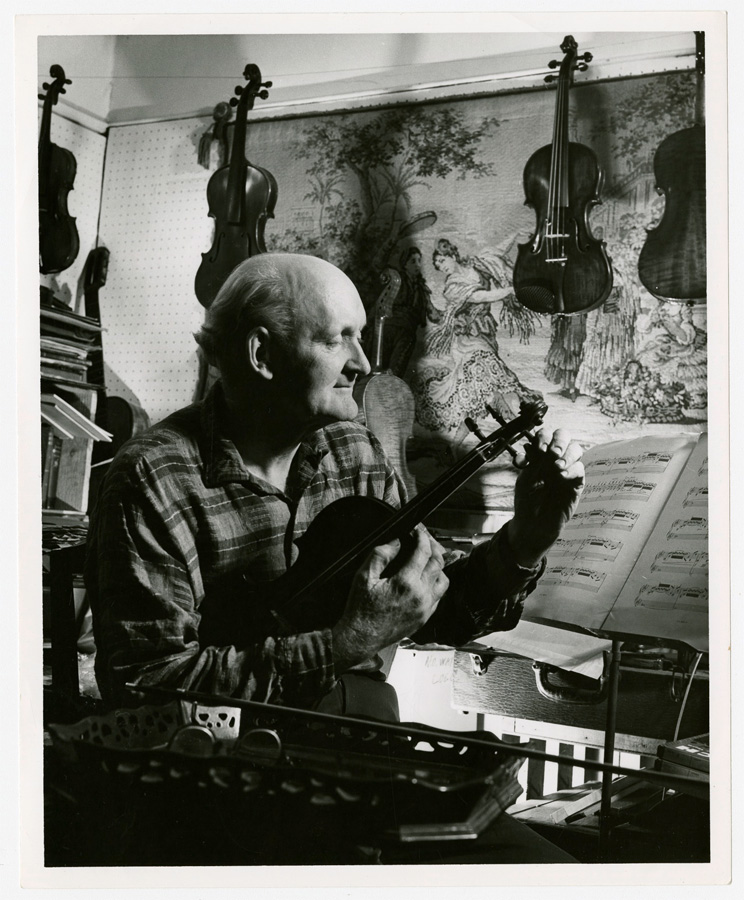

Russell, born in 1905 in Canton, Missouri, became an indefatigable jazz-record collector after he found a Jelly Roll Morton record that one of his students had left in the classroom at the school on Staten Island where he was a teacher. His work for the Jazzmen book brought him into contact with Bunk Johnson, an old trumpet player who had fallen on hard times. Russell helped Johnson get a new trumpet and began recording him in the early 1940s. By 1944, Russell had started his own record label, American Music, for the purpose of preserving the New Orleans style of music. Russell was not only interested in documenting the sound of current brass bands, the tradition of which some people feared was endangered in New Orleans; he also asked Johnson to put together a band of musicians who could recreate the older sound from the turn of the century. These recordings, made in the back yard of clarinet player George Lewis’s home in the French Quarter, are relics of an earlier time and remain invaluable to those interested in the history of New Orleans music. The importance of Russell’s work and dedication cannot be overstated. When he died in 1992, his obituary in the Times of London referred to him as “the single most influential figure in the revival of New Orleans jazz that began in the 1940s.”

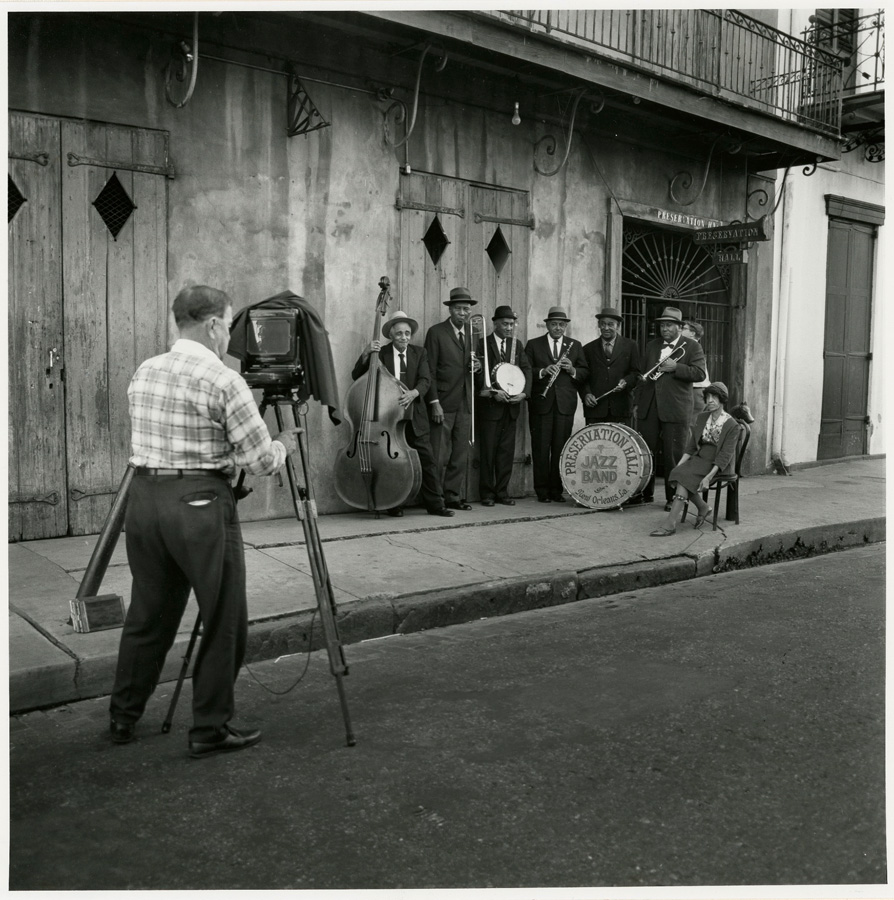

Russell operated his American Music label out of Chicago until 1956, when he relocated to New Orleans permanently, fulfilling perhaps his lifelong destiny. He was to become a regular character of the French Quarter for the next thirty-five years. In 1958 Russell was appointed the Curator of the Archive of New Orleans Jazz at Tulane University (now known as the Hogan Jazz Archive), where he began recording hundreds of oral histories with New Orleans musicians and their families. While working for Tulane, he continued running his record label, which is still in existence today, and also opened a record store in the French Quarter, originally on Chartres Street, and then later on St. Peter Street. Over the years Russell became a fixture at Preservation Hall, that jazz landmark at 726 St. Peter Street, which opened in 1961 and provided a venue for the same musicians whose legacies Russell had worked so hard to preserve.

However, jazz is not the only genre that has an important part in the musical culture of the French Quarter. New Orleans R&B and early rock ’n’ roll music has its own distinguished history, primarily embodied in the figure of famed sound engineer Cosimo Matassa. Born in New Orleans in 1926, Matassa attended Tulane University before opening J&M Studio at 840 N. Rampart Street, in the back of a record shop he ran there. The original recording area was only fifteen by sixteen feet, but his reputation as a talented sound engineer attracted a legendary line up of performers to his studio. Though it is impossible to say that one particular song is responsible for the start of rock ’n’ roll, Fats Domino’s release of the single “The Fat Man,” recorded at J&M Studio in 1949, is certainly one of the foundational moments in rock history. Essentially every important New Orleans R&B and rock ’n’ roll record made before 1970 was engineered by Matassa at J&M. Hits such as “Tutti Frutti”; “Good Golly, Miss Molly”; “Shake, Rattle and Roll”; and “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” were made there. New Orleans legends such as Dr. John, Allen Toussaint, Dave Bartholomew, James Booker, Irma Thomas, Harold Battiste, and Professor Longhair, among others, all recorded at Matassa’s studio. In 2010 the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame named J&M Studio, now a Laundromat, a historic rock ’n’ roll landmark; Matassa himself was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012.

New Orleans has such a diverse musical scene that nearly anyone can find a performance that appeals to them. Obviously musicians are the most important people in carrying forward the musical heritage of this city, but men like Bill Russell and Cosimo Matassa, long-term French Quarter fixtures both, were essential in recording and preserving those traditions and helping to bring them to national prominence. So go out and enjoy some live music this weekend, and remember the history that helped enshrine the French Quarter of New Orleans as one of the preeminent locales for music in America.

Jazz music was nurtured, if not born (that is a debate for another time), in the streets, bars, and nightclubs of New Orleans in the early part of the twentieth century. It was in and around Storyville, the notorious red-light district of New Orleans adjacent to the Quarter, that many of the early New Orleans jazz bands got their starts. However, a variety of factors, including the closure of Storyville in 1917, the onset of the Great Depression, and the increasing popularity of other styles of jazz in places like Chicago and New York, led to an erosion of interest in the New Orleans style of traditional jazz music. By the late 1930s many of the original New Orleans jazz musicians—at least the ones who hadn’t already left New Orleans for greener pastures—were aging and living in obscurity, sometimes even poverty. The publication of Jazzmen: The Story of Hot Jazz Told in the Lives of the Men Who Created It, edited by Frederic Ramsey and Charles Edward Smith, in 1939, helped bring the early history of jazz, and particularly the importance of New Orleans in that story, to a wider national audience. Significantly, a young jazz aficionado named Bill Russell contributed to that book.

Russell, born in 1905 in Canton, Missouri, became an indefatigable jazz-record collector after he found a Jelly Roll Morton record that one of his students had left in the classroom at the school on Staten Island where he was a teacher. His work for the Jazzmen book brought him into contact with Bunk Johnson, an old trumpet player who had fallen on hard times. Russell helped Johnson get a new trumpet and began recording him in the early 1940s. By 1944, Russell had started his own record label, American Music, for the purpose of preserving the New Orleans style of music. Russell was not only interested in documenting the sound of current brass bands, the tradition of which some people feared was endangered in New Orleans; he also asked Johnson to put together a band of musicians who could recreate the older sound from the turn of the century. These recordings, made in the back yard of clarinet player George Lewis’s home in the French Quarter, are relics of an earlier time and remain invaluable to those interested in the history of New Orleans music. The importance of Russell’s work and dedication cannot be overstated. When he died in 1992, his obituary in the Times of London referred to him as “the single most influential figure in the revival of New Orleans jazz that began in the 1940s.”

Russell operated his American Music label out of Chicago until 1956, when he relocated to New Orleans permanently, fulfilling perhaps his lifelong destiny. He was to become a regular character of the French Quarter for the next thirty-five years. In 1958 Russell was appointed the Curator of the Archive of New Orleans Jazz at Tulane University (now known as the Hogan Jazz Archive), where he began recording hundreds of oral histories with New Orleans musicians and their families. While working for Tulane, he continued running his record label, which is still in existence today, and also opened a record store in the French Quarter, originally on Chartres Street, and then later on St. Peter Street. Over the years Russell became a fixture at Preservation Hall, that jazz landmark at 726 St. Peter Street, which opened in 1961 and provided a venue for the same musicians whose legacies Russell had worked so hard to preserve.

However, jazz is not the only genre that has an important part in the musical culture of the French Quarter. New Orleans R&B and early rock ’n’ roll music has its own distinguished history, primarily embodied in the figure of famed sound engineer Cosimo Matassa. Born in New Orleans in 1926, Matassa attended Tulane University before opening J&M Studio at 840 N. Rampart Street, in the back of a record shop he ran there. The original recording area was only fifteen by sixteen feet, but his reputation as a talented sound engineer attracted a legendary line up of performers to his studio. Though it is impossible to say that one particular song is responsible for the start of rock ’n’ roll, Fats Domino’s release of the single “The Fat Man,” recorded at J&M Studio in 1949, is certainly one of the foundational moments in rock history. Essentially every important New Orleans R&B and rock ’n’ roll record made before 1970 was engineered by Matassa at J&M. Hits such as “Tutti Frutti”; “Good Golly, Miss Molly”; “Shake, Rattle and Roll”; and “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” were made there. New Orleans legends such as Dr. John, Allen Toussaint, Dave Bartholomew, James Booker, Irma Thomas, Harold Battiste, and Professor Longhair, among others, all recorded at Matassa’s studio. In 2010 the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame named J&M Studio, now a Laundromat, a historic rock ’n’ roll landmark; Matassa himself was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012.

New Orleans has such a diverse musical scene that nearly anyone can find a performance that appeals to them. Obviously musicians are the most important people in carrying forward the musical heritage of this city, but men like Bill Russell and Cosimo Matassa, long-term French Quarter fixtures both, were essential in recording and preserving those traditions and helping to bring them to national prominence. So go out and enjoy some live music this weekend, and remember the history that helped enshrine the French Quarter of New Orleans as one of the preeminent locales for music in America.