February 03, 2017

Walk down Chartres, Royal, or Canal Street today, and you will see shopwindows filled with sparkling jewelry, stylish clothing, trendy household goods, and elegant furniture. If you did the same thing 150 years ago, you would see similar displays in many of the same windows. The exhibition Goods of Every Description: Shopping in New Orleans, 1825–1925, now on display at The Historic New Orleans Collection, illustrates the types of luxury goods from around the world and some of the stores customers visited along the shopping avenues of old New Orleans.

In the early nineteenth century, Chartres Street was the main place for fashionable shopping. Silversmiths, china dealers, and textile merchants lined the street. French trained orfevres, or jewelers, such as Jean-Noel Delarue set up their workshops in small buildings. Although Delarue was one of the most prolific early New Orleans silversmiths, making forks and spoons in the contemporary French style, his silver shop also sold jewelry and other goods in that he had picked up on repeated trips back to France. Silversmith Anthony Rasch set up his workshop at 75 Chartres Street. Rasch, the second son of a German count, was trained in France and worked in Philadelphia before he moved to New Orleans in 1820. He advertised silverware in “either French or English taste,” which he sold alongside imported Sheffield plate, silver from France and Philadelphia, and Saratoga mineral water.

Other fashionable goods were available on Chartres Street for New Orleans customers with French tastes. Brothers Valsin and Oscar Vignaud used their merchant connections to import fine French porcelain to sell in their shop in the French Quarter: Valsin was part-owner of a merchant brig and Oscar was a skilled advertiser and salesman. One of their customers was Governor A. B. Roman, who purchased a 150-piece china set in the Cornflower pattern around 1840. A block down, John Gauche, an immigrant from Alsace-Lorraine, was a very successful china dealer, importing French porcelain, English earthenware, and American and Bohemian glass to his expanding store on Chartres Street.

The shop spaces along the old streets in the French Quarter were small, and in the middle of the nineteenth century several businesses that had first been established on Chartres Street moved to larger real estate on Canal Street. James Nevins Hyde set up a branch of his New York silver business on Chartres Street in 1817, selling eyeglasses and pens imported from his manufacturing ties in the Northeast. He was soon in business with his brother-in-law Charles Whiting Goodrich. The original Hyde & Goodrich store was located at 15 Chartres Street, but the store moved to the new Touro Buildings at the corner of Canal and Royal Streets in 1853. The popular silver store was a shopping destination, marked by a large golden pelican perched on the balcony, with showy window displays of fine tea sets made by local silversmiths, named silver patterns from northern manufacturers, and even patented pistols imported from England. Hyde & Goodrich remained a successful family business, with management descending to sons and sons-in-law of the founders. By 1865, the firm was operating under the name A. B. Griswold and continued to be a retailer for popular silver patterns and jewelry.

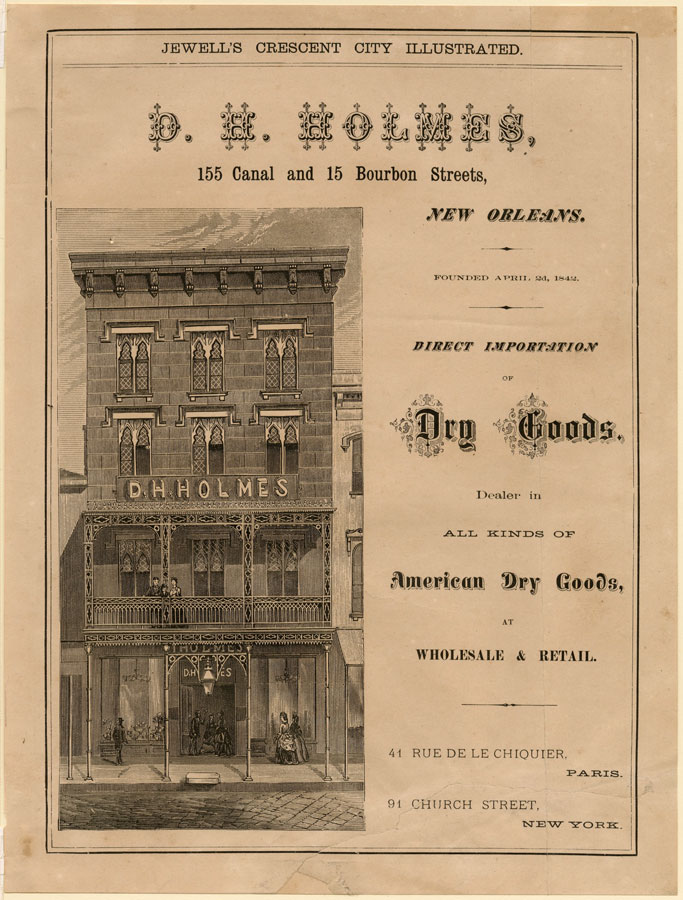

Another well-known Canal Street business that got its start on Chartres Street was D. H. Holmes. Daniel Henry Holmes started a dry goods store in the French Quarter in 1842, serving as a direct importer for all types of textiles, from fine silks for evening gowns to rough cloth for enslaved people’s clothing. In 1849, Holmes sought larger real estate and was one of the first major businesses to move to Canal Street. Over the next century, D. H. Holmes expanded to include departments for women’s clothing, men’s clothing, hosiery, and household textiles, and even a restaurant, until it was the largest department store in the South and a landmark on Canal Street.

As the “Great Wide Way” in the center of New Orleans, Canal Street became the main shopping avenue in the second half of the nineteenth century. The first retail businesses established on Canal Street sold cheap English earthenware and American crockery. Established at the base of Canal Street by 1825, Hill & Henderson and its successor Henderson & Gaines were responsible for thousands of crates of pottery that came through the port of New Orleans. The firm was an agent for the Davenport pottery in Staffordshire, England, and dishes bearing the retailer’s mark have been found in archaeological digs throughout the Mississippi Valley.

By the latter part of the century, other retailers sold ceramics of all types, styles, and price ranges in china emporiums along Canal Street and the blocks close by in what is now the Central Business district. One such dealer was E. Offner, whose shop was filled with “fancy and plain” china. Offner was a dealer for the Haviland Company, the largest manufacturer of French porcelain for the American market.

Some of the best clothing stores also relocated to Canal Street after the Civil War. Olympe Boisse moved her millinery and dressmaking shop from Chartres Street to Canal Street in 1864. Known as Madame Olympe, she was regarded as the best modiste in the city, offering gowns, bonnets, wraps, and artificial flowers of the highest quality and the latest styles. At the end of each summer, she traveled to Paris, returning in the fall with dresses, fabrics, and accessories in the current fashions, as well as skilled dressmakers to create custom clothing for the women of the city, just in time for the winter season of theater and Mardi Gras balls.

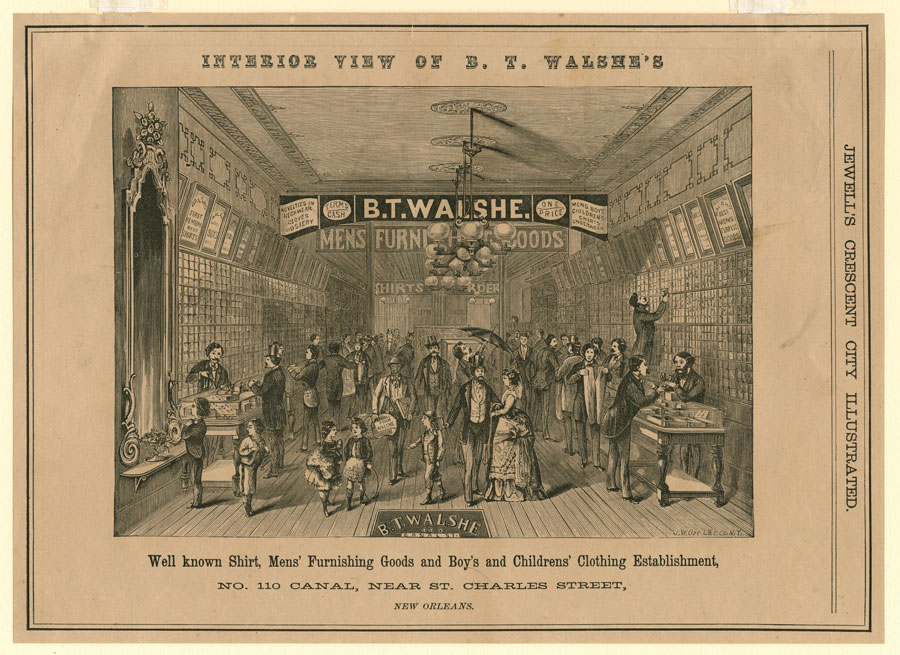

Blayney T. Walshe opened his men’s clothing store on Canal Street in 1868, selling ready-made clothing, silk cravats, and custom shirts. Like Madame Olympe, B. T. Walshe traveled annually, visiting New York to select stock for his store. Other clothing stores on or near Canal Street included Imperial Shoes, Terry and Juden, and the ever-growing department stores.

At the end of the nineteenth century, one of the largest stores on Canal Street was Maison Blanche. The first purpose-built department store in New Orleans, Maison Blanche had five stories divided into departments, including leather goods, jewelry, stationery, ladies’ clothing, men’s furnishings, toys, upholstery, and bric-a-brac.

Shoppers seeking fashionable furniture need not have looked further than Royal Street. Known as “Furniture Row” by 1860, the first few blocks of Royal Street had the largest concentration of furniture retailers in the city. Store after store offered parlor suites, beds, dining sets, carpets, curtains, mirrors, and miscellaneous “fancy goods” in the latest nineteenth-century revival styles. Retailers such as Prudent Mallard, William McCracken, and Henry Siebrecht received constant shipments of furniture from manufacturers in New York, Boston, Cincinnati, and France to fill their warehouses. They employed craftsmen to assemble, upholster, and install new furniture, curtains, and wallpaper for their customers in the city and up the river.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the former street of fashionable new furniture stores evolved into a destination for antiques. These antiques stores—such as Waldhorn’s, Keil’s, and Manheim’s—carried on the legacy of retail and shopping established by earlier retailers. To meet local demands, they imported antiques from France and the Northeast, selling them alongside pieces that had been passed through generations after having been purchased originally on the shopping thoroughfares of old New Orleans.

In the early nineteenth century, Chartres Street was the main place for fashionable shopping. Silversmiths, china dealers, and textile merchants lined the street. French trained orfevres, or jewelers, such as Jean-Noel Delarue set up their workshops in small buildings. Although Delarue was one of the most prolific early New Orleans silversmiths, making forks and spoons in the contemporary French style, his silver shop also sold jewelry and other goods in that he had picked up on repeated trips back to France. Silversmith Anthony Rasch set up his workshop at 75 Chartres Street. Rasch, the second son of a German count, was trained in France and worked in Philadelphia before he moved to New Orleans in 1820. He advertised silverware in “either French or English taste,” which he sold alongside imported Sheffield plate, silver from France and Philadelphia, and Saratoga mineral water.

Other fashionable goods were available on Chartres Street for New Orleans customers with French tastes. Brothers Valsin and Oscar Vignaud used their merchant connections to import fine French porcelain to sell in their shop in the French Quarter: Valsin was part-owner of a merchant brig and Oscar was a skilled advertiser and salesman. One of their customers was Governor A. B. Roman, who purchased a 150-piece china set in the Cornflower pattern around 1840. A block down, John Gauche, an immigrant from Alsace-Lorraine, was a very successful china dealer, importing French porcelain, English earthenware, and American and Bohemian glass to his expanding store on Chartres Street.

The shop spaces along the old streets in the French Quarter were small, and in the middle of the nineteenth century several businesses that had first been established on Chartres Street moved to larger real estate on Canal Street. James Nevins Hyde set up a branch of his New York silver business on Chartres Street in 1817, selling eyeglasses and pens imported from his manufacturing ties in the Northeast. He was soon in business with his brother-in-law Charles Whiting Goodrich. The original Hyde & Goodrich store was located at 15 Chartres Street, but the store moved to the new Touro Buildings at the corner of Canal and Royal Streets in 1853. The popular silver store was a shopping destination, marked by a large golden pelican perched on the balcony, with showy window displays of fine tea sets made by local silversmiths, named silver patterns from northern manufacturers, and even patented pistols imported from England. Hyde & Goodrich remained a successful family business, with management descending to sons and sons-in-law of the founders. By 1865, the firm was operating under the name A. B. Griswold and continued to be a retailer for popular silver patterns and jewelry.

Another well-known Canal Street business that got its start on Chartres Street was D. H. Holmes. Daniel Henry Holmes started a dry goods store in the French Quarter in 1842, serving as a direct importer for all types of textiles, from fine silks for evening gowns to rough cloth for enslaved people’s clothing. In 1849, Holmes sought larger real estate and was one of the first major businesses to move to Canal Street. Over the next century, D. H. Holmes expanded to include departments for women’s clothing, men’s clothing, hosiery, and household textiles, and even a restaurant, until it was the largest department store in the South and a landmark on Canal Street.

As the “Great Wide Way” in the center of New Orleans, Canal Street became the main shopping avenue in the second half of the nineteenth century. The first retail businesses established on Canal Street sold cheap English earthenware and American crockery. Established at the base of Canal Street by 1825, Hill & Henderson and its successor Henderson & Gaines were responsible for thousands of crates of pottery that came through the port of New Orleans. The firm was an agent for the Davenport pottery in Staffordshire, England, and dishes bearing the retailer’s mark have been found in archaeological digs throughout the Mississippi Valley.

By the latter part of the century, other retailers sold ceramics of all types, styles, and price ranges in china emporiums along Canal Street and the blocks close by in what is now the Central Business district. One such dealer was E. Offner, whose shop was filled with “fancy and plain” china. Offner was a dealer for the Haviland Company, the largest manufacturer of French porcelain for the American market.

Some of the best clothing stores also relocated to Canal Street after the Civil War. Olympe Boisse moved her millinery and dressmaking shop from Chartres Street to Canal Street in 1864. Known as Madame Olympe, she was regarded as the best modiste in the city, offering gowns, bonnets, wraps, and artificial flowers of the highest quality and the latest styles. At the end of each summer, she traveled to Paris, returning in the fall with dresses, fabrics, and accessories in the current fashions, as well as skilled dressmakers to create custom clothing for the women of the city, just in time for the winter season of theater and Mardi Gras balls.

Blayney T. Walshe opened his men’s clothing store on Canal Street in 1868, selling ready-made clothing, silk cravats, and custom shirts. Like Madame Olympe, B. T. Walshe traveled annually, visiting New York to select stock for his store. Other clothing stores on or near Canal Street included Imperial Shoes, Terry and Juden, and the ever-growing department stores.

At the end of the nineteenth century, one of the largest stores on Canal Street was Maison Blanche. The first purpose-built department store in New Orleans, Maison Blanche had five stories divided into departments, including leather goods, jewelry, stationery, ladies’ clothing, men’s furnishings, toys, upholstery, and bric-a-brac.

Shoppers seeking fashionable furniture need not have looked further than Royal Street. Known as “Furniture Row” by 1860, the first few blocks of Royal Street had the largest concentration of furniture retailers in the city. Store after store offered parlor suites, beds, dining sets, carpets, curtains, mirrors, and miscellaneous “fancy goods” in the latest nineteenth-century revival styles. Retailers such as Prudent Mallard, William McCracken, and Henry Siebrecht received constant shipments of furniture from manufacturers in New York, Boston, Cincinnati, and France to fill their warehouses. They employed craftsmen to assemble, upholster, and install new furniture, curtains, and wallpaper for their customers in the city and up the river.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the former street of fashionable new furniture stores evolved into a destination for antiques. These antiques stores—such as Waldhorn’s, Keil’s, and Manheim’s—carried on the legacy of retail and shopping established by earlier retailers. To meet local demands, they imported antiques from France and the Northeast, selling them alongside pieces that had been passed through generations after having been purchased originally on the shopping thoroughfares of old New Orleans.