November 02, 2015

The French Quarter is a popular party destination, where travelers come to seek out food, music, nightlife, and an all-around good time. Any holiday can be cause for a celebration in New Orleans, but New Year’s Eve is one of the most significant and has been since the earliest days of the city’s existence. As the New Orleans author Hartnett Kane wrote, “Christmas was the day for solemnity, for religion, and for family observance; New Year’s the time for conviviality. The holidays reached their climax on New Year’s Day, le Jour de l’An –the day of the year in more ways than one.”

During the course of the nineteenth century, the Creole community of New Orleans, centered in the French Quarter, developed holiday traditions that were different from the more American areas of the city. For a Creole family, New Year’s Eve would almost certainly be celebrated with the réveillon dinner (also celebrated on Christmas Eve) at a friend or family member’s home. The word comes from the French réveil, which means “waking,” because the participants would stay awake until midnight or later. The réveillon was a particularly sumptuous party and feast, with food of the richest ingredients and plenty of alcohol to go around, as well.

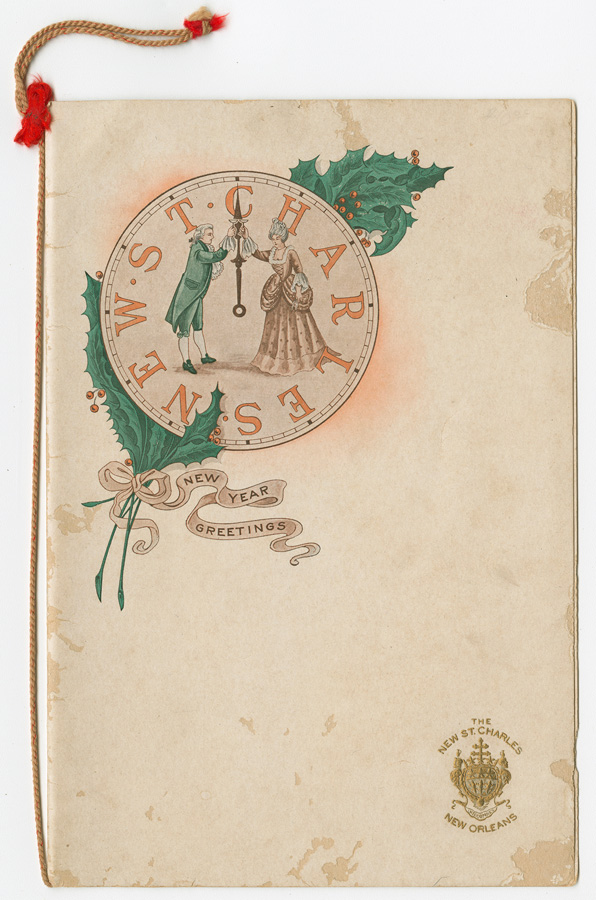

For those venturing outside on New Year’s Eve, Canal Street in particular was a center of activity, with crowds of people making noise, ringing bells, and shooting off fireworks. Despite being outlawed, roman candles and firecrackers were common, and sometimes merrymakers shot guns into the air in addition to the fireworks, with occasional reports of revelers getting hurt by falling bullets. Marching bands roamed the streets of the Quarter, adding to the chaotic spectacle with their instruments echoing against the buildings of the neighborhood. Residents would open their doors to the bands and offer refreshments as thanks for their efforts. Theaters and opera houses often put on evening shows, after which audience members would imbibe at bars in the city’s prominent hotels or head back home for their réveillon. As the stroke of midnight neared, all the ships on the Mississippi River would blast their horns as the entire city would build to a deafening clamor.

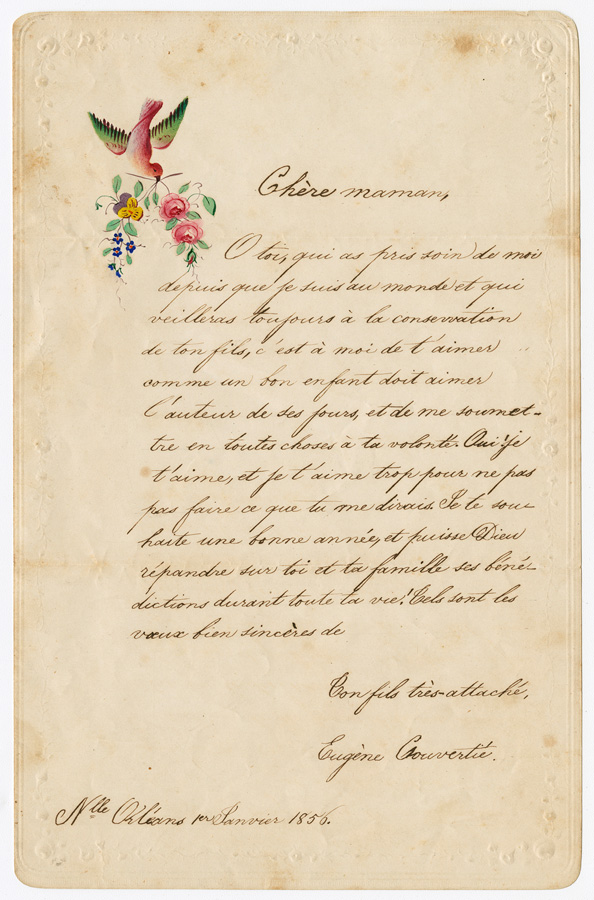

New Year’s Day had its own set of social and familial traditions. In the morning, Creole children were given elaborate gifts—china dolls from France for the girls, and elaborate toy soldiers, toy guns, or hobby horses for the boys. Unlike their American counterparts, on Christmas Creole children were only given a few candies and trinkets in their stockings. The bigger and more expensive gifts from their parents arrived on New Year’s Day. In return, the Creole children would present their parents with handwritten cards with short verses inside, called complement du jour de l'an, printed on pink paper with a pink envelope, wishing the best for the New Year. Hartnett Kane offers a sample of such a verse, writing, “My dear Mamam, my dear Papa, / A good New Year... / I salute and love you / With a love everlasting.” After this ritual, breakfast followed, likely consisting of grits and grillades (a kind of stew made with beef medallions) or pain perdu (French toast), and pots of hot coffee.

The rest of the day was left for visiting friends and relatives, who hosted open houses all over the city. Godparents (always important in this Catholic city), grandparents, and other older relatives were first in line, with friends to follow later throughout the day. Guests were greeted in the parlor with various types of cakes and a large bowl of eggnog. Dragées, a type of sugared almond, were typical, as were bonbons and the great Creole specialty, the praline. Men might be offered wine, brandy, or even whiskey, while women sipped on liqueurs and cordials. For family, these visits were a chance to catch up on news and gossip. Often family members from outside of town would venture into the city for the day.

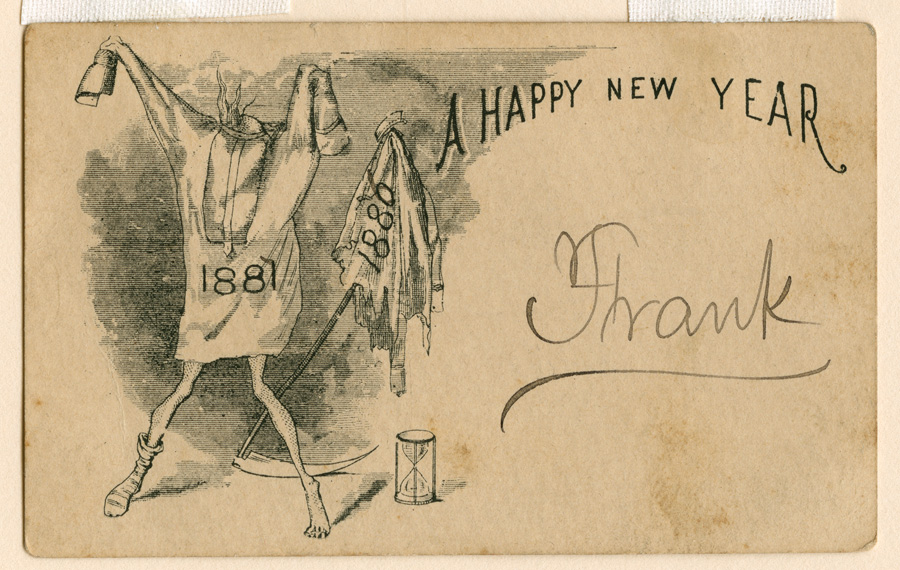

For young men and women of Creole society, the day was a chance to court the opposite sex. The men dressed in their finest pants and high collared shirts and fancy silk hats and visited various ladies of their acquaintance, sometimes as many as twenty visits over the course of the day. They would present the lady in the house with a small cornucopia of sweets, have a drink, something to eat, and then move on to the next house. The ladies also had small baskets by the doorway where the callers would drop their card. At the end of the day, the women would count the number of cards in their basket and compete to see who had accumulated the most.

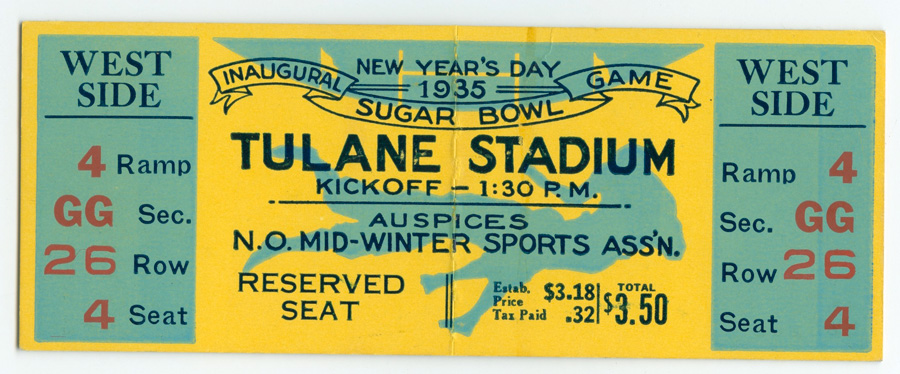

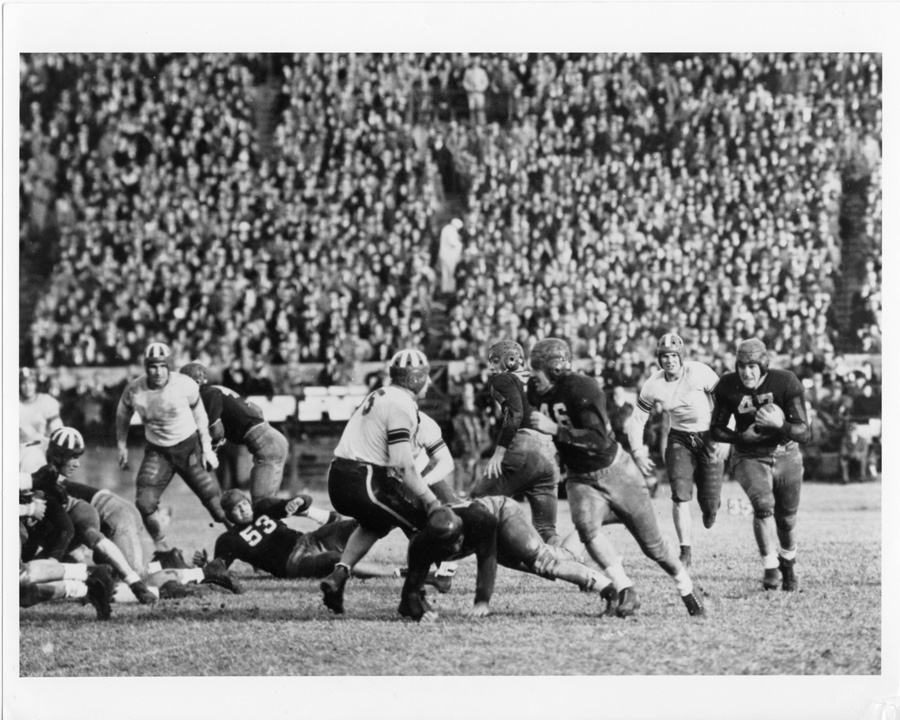

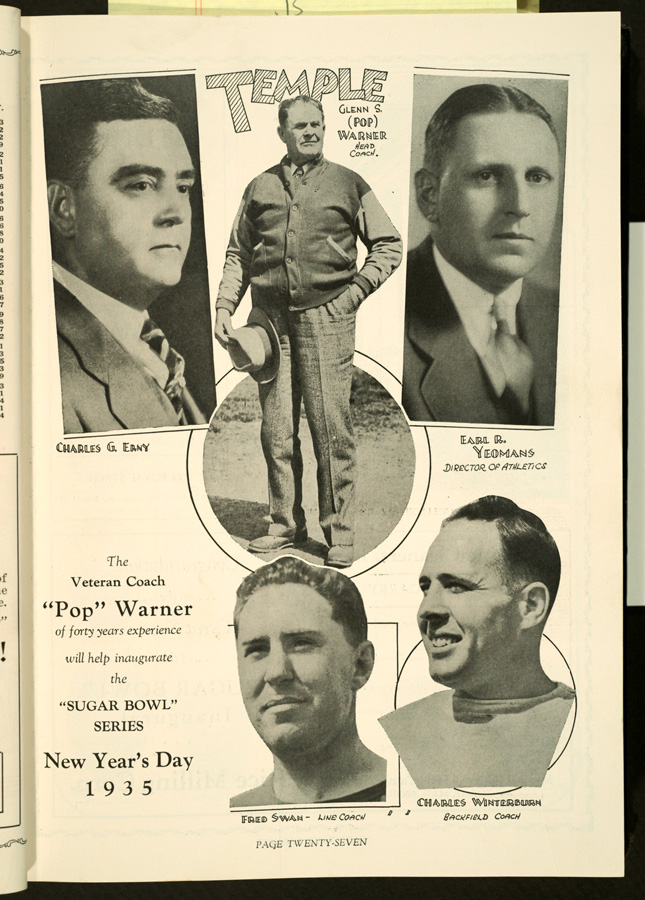

As the twentieth century unfolded these old Creole traditions began to fade. Writing in 1912, author Eliza Ripley bemoaned the fact that no one called on New Year’s Day anymore and that it had become a “dull” and “stupid” holiday. Anyone with the means retreated to a country estate for the holiday, and all the stores were closed. As the 1920s wore on, businessmen in town saw an opportunity to revitalize the holiday for the city, an effort that led to the city’s first Sugar Bowl in 1935. At Tulane Stadium, in front of a capacity crowd, the hometown Tulane University team defeated Temple University 20-14. The New Orleans States, a local newspaper, wrote that the game had “the noisiest and most enthusiastic greeting to a new year since the depression.” The game would become a yearly tradition, and today it is perhaps the event most closely connected with New Year’s celebrations in New Orleans.

Today, New Year’s Eve is celebrated in the French Quarter with fireworks along the Mississippi River, and a black and gold fleur-de-lis is dropped from the top of Jax Brewery at the stroke of midnight, but traces of the older traditions remain, too. A slightly modified version of the réveillon has survived into the twenty-first century, though it has largely moved into the well-known restaurants of the French Quarter in the form of prix frixe (fixed price menus), and noise, music, and chaos still rule the night. Ultimately, New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day in New Orleans has always been a social holiday best shared by friends and loved ones with fellowship and good cheer.

During the course of the nineteenth century, the Creole community of New Orleans, centered in the French Quarter, developed holiday traditions that were different from the more American areas of the city. For a Creole family, New Year’s Eve would almost certainly be celebrated with the réveillon dinner (also celebrated on Christmas Eve) at a friend or family member’s home. The word comes from the French réveil, which means “waking,” because the participants would stay awake until midnight or later. The réveillon was a particularly sumptuous party and feast, with food of the richest ingredients and plenty of alcohol to go around, as well.

For those venturing outside on New Year’s Eve, Canal Street in particular was a center of activity, with crowds of people making noise, ringing bells, and shooting off fireworks. Despite being outlawed, roman candles and firecrackers were common, and sometimes merrymakers shot guns into the air in addition to the fireworks, with occasional reports of revelers getting hurt by falling bullets. Marching bands roamed the streets of the Quarter, adding to the chaotic spectacle with their instruments echoing against the buildings of the neighborhood. Residents would open their doors to the bands and offer refreshments as thanks for their efforts. Theaters and opera houses often put on evening shows, after which audience members would imbibe at bars in the city’s prominent hotels or head back home for their réveillon. As the stroke of midnight neared, all the ships on the Mississippi River would blast their horns as the entire city would build to a deafening clamor.

New Year’s Day had its own set of social and familial traditions. In the morning, Creole children were given elaborate gifts—china dolls from France for the girls, and elaborate toy soldiers, toy guns, or hobby horses for the boys. Unlike their American counterparts, on Christmas Creole children were only given a few candies and trinkets in their stockings. The bigger and more expensive gifts from their parents arrived on New Year’s Day. In return, the Creole children would present their parents with handwritten cards with short verses inside, called complement du jour de l'an, printed on pink paper with a pink envelope, wishing the best for the New Year. Hartnett Kane offers a sample of such a verse, writing, “My dear Mamam, my dear Papa, / A good New Year... / I salute and love you / With a love everlasting.” After this ritual, breakfast followed, likely consisting of grits and grillades (a kind of stew made with beef medallions) or pain perdu (French toast), and pots of hot coffee.

The rest of the day was left for visiting friends and relatives, who hosted open houses all over the city. Godparents (always important in this Catholic city), grandparents, and other older relatives were first in line, with friends to follow later throughout the day. Guests were greeted in the parlor with various types of cakes and a large bowl of eggnog. Dragées, a type of sugared almond, were typical, as were bonbons and the great Creole specialty, the praline. Men might be offered wine, brandy, or even whiskey, while women sipped on liqueurs and cordials. For family, these visits were a chance to catch up on news and gossip. Often family members from outside of town would venture into the city for the day.

For young men and women of Creole society, the day was a chance to court the opposite sex. The men dressed in their finest pants and high collared shirts and fancy silk hats and visited various ladies of their acquaintance, sometimes as many as twenty visits over the course of the day. They would present the lady in the house with a small cornucopia of sweets, have a drink, something to eat, and then move on to the next house. The ladies also had small baskets by the doorway where the callers would drop their card. At the end of the day, the women would count the number of cards in their basket and compete to see who had accumulated the most.

As the twentieth century unfolded these old Creole traditions began to fade. Writing in 1912, author Eliza Ripley bemoaned the fact that no one called on New Year’s Day anymore and that it had become a “dull” and “stupid” holiday. Anyone with the means retreated to a country estate for the holiday, and all the stores were closed. As the 1920s wore on, businessmen in town saw an opportunity to revitalize the holiday for the city, an effort that led to the city’s first Sugar Bowl in 1935. At Tulane Stadium, in front of a capacity crowd, the hometown Tulane University team defeated Temple University 20-14. The New Orleans States, a local newspaper, wrote that the game had “the noisiest and most enthusiastic greeting to a new year since the depression.” The game would become a yearly tradition, and today it is perhaps the event most closely connected with New Year’s celebrations in New Orleans.

Today, New Year’s Eve is celebrated in the French Quarter with fireworks along the Mississippi River, and a black and gold fleur-de-lis is dropped from the top of Jax Brewery at the stroke of midnight, but traces of the older traditions remain, too. A slightly modified version of the réveillon has survived into the twenty-first century, though it has largely moved into the well-known restaurants of the French Quarter in the form of prix frixe (fixed price menus), and noise, music, and chaos still rule the night. Ultimately, New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day in New Orleans has always been a social holiday best shared by friends and loved ones with fellowship and good cheer.