August 04, 2015

Grabbing an ice-cold lemonade or a cocktail and strolling through the French Quarter is one of the nicest ways to spend a summer day in New Orleans. The oldest neighborhood in the city, the French Quarter offers an abundance of entertainment. If your tastes are more artistically minded, then you’ll find plenty to occupy your time. A portion of Royal Street converts into a pedestrian mall during the day, and the myriad art galleries and antique shops open their doors to anyone ambling down the street. Street artists also set up their work for passersby against the iron fencing around Jackson Square and behind St. Louis Cathedral at Orleans and Royal. Art in and around the Quarter feels ubiquitous—it’s as if the art, and the artists who make it, are part of the very essence of the neighborhood.

Much of this tradition of artists living and working in the French Quarter can be traced to the history and enduring legacy of the New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club. The Arts and Crafts movement, an international trend in the art world, emerged out of England during the late Victorian period and was a push back against industrialization. Machine-made goods were perceived as soul-less and were thought to lack the higher quality of handmade items. The Arts and Crafts movement promoted craftsmanship, particularly in the decorative and visual arts.

The most prominent example of the Arts and Craft movement in New Orleans is the world-renowned Newcomb Pottery, produced by the female art students at Newcomb College, now incorporated into Tulane University. However, it was the creation of the New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club in 1922 that firmly established the French Quarter as the center of visual arts production in the city.

In the early twentieth century the French Quarter was in the midst of a decline. Much of the historic architecture that attracts millions of tourists to the Quarter today was threatened with demolition, and some buildings, such as the St. Louis Hotel and the French Opera House, had already been lost. A group of preservationists and artists, mourning these losses, began meeting at painter Alberta Kinsey’s apartment on Toulouse Street around 1919 and offering art classes. Over a few year this group, which had also acquired gallery space, began to attract some wealthy donors and patrons, including Sarah Henderson, a sugar refinery heiress, who became one of the main financial supporters and leaders of the club.

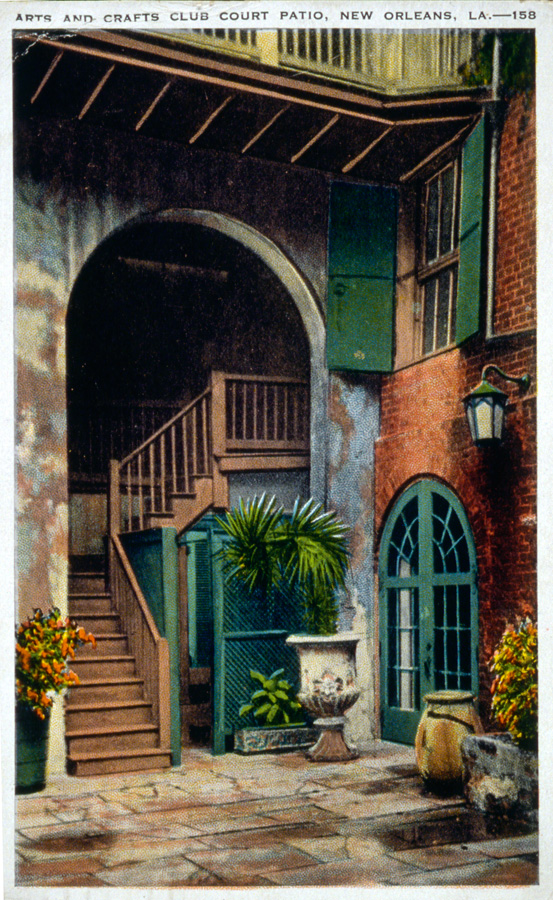

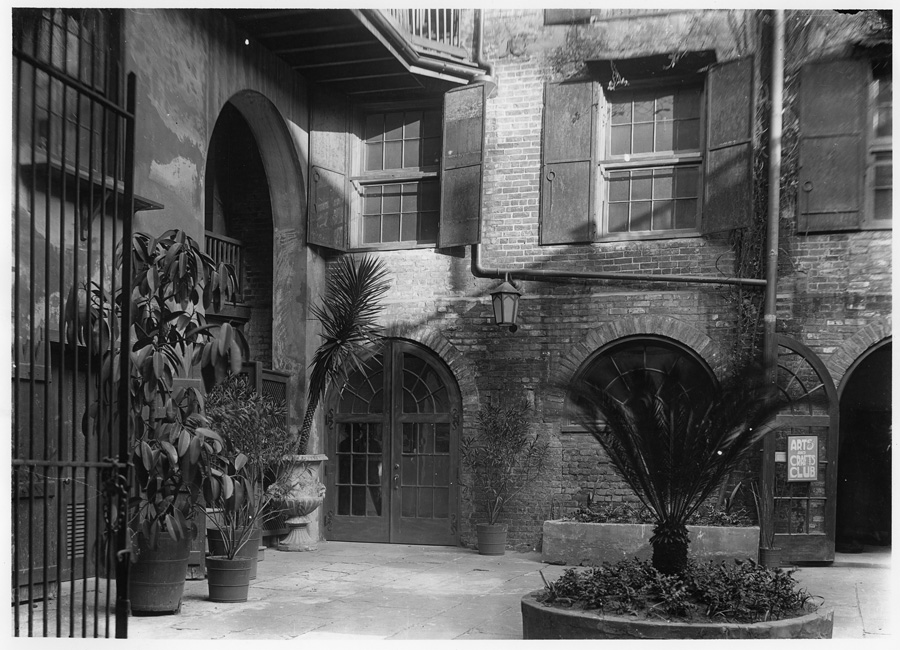

The group formally incorporated as the New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club on June 2, 1922. Originally meeting at 710 St. Peter Street, they soon moved to 520 Royal Street, the location of the famous Seignouret-Brulatour building, whose owner, W. R. Irby, a preservationist himself, had outfitted for the club's use. During the residency of the Arts and Crafts Club at that location, the lovely courtyard of the building would become one of the most commonly depicted scenes in all of New Orleans.

The purpose of the club, as described in their official charter was:

to foster higher artistic standards; to establish and maintain classes in the different branches of the arts and crafts and to give instruction therein; to enable artists, craftsmen and the public to get in touch with each other and provide facilities for same; to maintain a permanent club, and an exhibition room for display of the products of arts and crafts; to keep its members in touch with current literature and teachings on the arts and crafts; to aid and assist generally in the promotion and development of arts and crafts.

For the duration of the club, it was successful in achieving these goals. Membership shot up to more than 500 members and was open not just to professional or working artists, but to lay people and patrons interested in art. In fact, its board of directors was primarily made up of wealthy art aficionados rather than artists themselves. The group opened and ran the New Orleans Art School, offering classes in painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking, pottery, and architecture. The school helped train some of the of the most important New Orleans artists of the twentieth century, including Boyd Cruise (also the first director of The Historic New Orleans Collection), Josephine Crawford, Juanita Gonzales, and John McCrady (who would later open up his own art school on Bourbon Street).

The teaching faculty was possibly even more accomplished, including such notables as William Spratling, Clarence Millet, Will Henry Stevens, Caroline Durieux, and Enrique Alférez. The exhibitions held by the club were important in bringing modern art to New Orleans, and in the late 1930s they showcased art from Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Juan Gris, André Derain, Georges Rouault, Joan Miró, and Salvador Dalí. Through connections with Tulane and Newcomb faculty members the group also participated in the intellectual life of New Orleans by hosting lectures on anthropology, archaeology, history, and art history.

The club was also very important in the social life of the Quarter. It served as one of the most prominent vehicles through which young, bohemian French Quarter artists were met older, wealthier art-lovers who lived Uptown and in the Garden District. The scholar John Shelton Reed dubbed this time period of the 1920s “the French Quarter Renaissance” and has referred to it as a “Dixie Bohemia.” The club put on an eagerly anticipated artist ball every year, which required elaborate costumes for the attendees and promised scandalous entertainment. Originally only for members of the club and students enrolled at the school, within a few years the party had morphed into a fundraiser for the club, helping maintain its facilities and the school Area newspapers enthusiastically covered the ball and its guest list in society columns.

Despite the popularity of the ball, the club never fully succeeded in meeting its ambitious financial needs and was always underwritten by some of its wealthier patrons, particularly Sarah Henderson. The arrival of the Great Depression put the club under further financial strain. In 1933 the Club moved its headquarters to a building Henderson owned at 712 Royal Street. They continued hosting exhibitions and teaching classes, but the nature of the French Quarter was changing, too. The somewhat unusual alliance between the wealthy Uptowners and the artistic Quarter dwellers could not be sustained indefinitely. After Henderson died in 1944, the Club moved again in 1948, and it was eventually forced to shut its doors in 1951. Ironically, the success of the preservation movement, with which the club was so intimately connected, led to the decline of the bohemian lifestyle that had provided so much of the club’s vitality in the first place. In this way, the thirty-year history of the Club parallels the evolution of the French Quarter. The legacy of the New Orleans Arts and Craft Club is immense. The accomplishments of the individual artists trained and/or showcased by the club significant on their own, but the club and its artists introduced New Orleans as a whole to a modern idea of art. Perhaps most importantly, however, was the focus on the French Quarter as the axis mundi of art and culture in the city, which still resonates so strongly today. That idea and feeling, which seems so fundamental now, was by no means inevitable. It is a testament to the influence and lasting importance of the New Orleans Arts and Craft Club.

Much of this tradition of artists living and working in the French Quarter can be traced to the history and enduring legacy of the New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club. The Arts and Crafts movement, an international trend in the art world, emerged out of England during the late Victorian period and was a push back against industrialization. Machine-made goods were perceived as soul-less and were thought to lack the higher quality of handmade items. The Arts and Crafts movement promoted craftsmanship, particularly in the decorative and visual arts.

The most prominent example of the Arts and Craft movement in New Orleans is the world-renowned Newcomb Pottery, produced by the female art students at Newcomb College, now incorporated into Tulane University. However, it was the creation of the New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club in 1922 that firmly established the French Quarter as the center of visual arts production in the city.

In the early twentieth century the French Quarter was in the midst of a decline. Much of the historic architecture that attracts millions of tourists to the Quarter today was threatened with demolition, and some buildings, such as the St. Louis Hotel and the French Opera House, had already been lost. A group of preservationists and artists, mourning these losses, began meeting at painter Alberta Kinsey’s apartment on Toulouse Street around 1919 and offering art classes. Over a few year this group, which had also acquired gallery space, began to attract some wealthy donors and patrons, including Sarah Henderson, a sugar refinery heiress, who became one of the main financial supporters and leaders of the club.

The group formally incorporated as the New Orleans Arts and Crafts Club on June 2, 1922. Originally meeting at 710 St. Peter Street, they soon moved to 520 Royal Street, the location of the famous Seignouret-Brulatour building, whose owner, W. R. Irby, a preservationist himself, had outfitted for the club's use. During the residency of the Arts and Crafts Club at that location, the lovely courtyard of the building would become one of the most commonly depicted scenes in all of New Orleans.

The purpose of the club, as described in their official charter was:

to foster higher artistic standards; to establish and maintain classes in the different branches of the arts and crafts and to give instruction therein; to enable artists, craftsmen and the public to get in touch with each other and provide facilities for same; to maintain a permanent club, and an exhibition room for display of the products of arts and crafts; to keep its members in touch with current literature and teachings on the arts and crafts; to aid and assist generally in the promotion and development of arts and crafts.

For the duration of the club, it was successful in achieving these goals. Membership shot up to more than 500 members and was open not just to professional or working artists, but to lay people and patrons interested in art. In fact, its board of directors was primarily made up of wealthy art aficionados rather than artists themselves. The group opened and ran the New Orleans Art School, offering classes in painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking, pottery, and architecture. The school helped train some of the of the most important New Orleans artists of the twentieth century, including Boyd Cruise (also the first director of The Historic New Orleans Collection), Josephine Crawford, Juanita Gonzales, and John McCrady (who would later open up his own art school on Bourbon Street).

The teaching faculty was possibly even more accomplished, including such notables as William Spratling, Clarence Millet, Will Henry Stevens, Caroline Durieux, and Enrique Alférez. The exhibitions held by the club were important in bringing modern art to New Orleans, and in the late 1930s they showcased art from Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Juan Gris, André Derain, Georges Rouault, Joan Miró, and Salvador Dalí. Through connections with Tulane and Newcomb faculty members the group also participated in the intellectual life of New Orleans by hosting lectures on anthropology, archaeology, history, and art history.

The club was also very important in the social life of the Quarter. It served as one of the most prominent vehicles through which young, bohemian French Quarter artists were met older, wealthier art-lovers who lived Uptown and in the Garden District. The scholar John Shelton Reed dubbed this time period of the 1920s “the French Quarter Renaissance” and has referred to it as a “Dixie Bohemia.” The club put on an eagerly anticipated artist ball every year, which required elaborate costumes for the attendees and promised scandalous entertainment. Originally only for members of the club and students enrolled at the school, within a few years the party had morphed into a fundraiser for the club, helping maintain its facilities and the school Area newspapers enthusiastically covered the ball and its guest list in society columns.

Despite the popularity of the ball, the club never fully succeeded in meeting its ambitious financial needs and was always underwritten by some of its wealthier patrons, particularly Sarah Henderson. The arrival of the Great Depression put the club under further financial strain. In 1933 the Club moved its headquarters to a building Henderson owned at 712 Royal Street. They continued hosting exhibitions and teaching classes, but the nature of the French Quarter was changing, too. The somewhat unusual alliance between the wealthy Uptowners and the artistic Quarter dwellers could not be sustained indefinitely. After Henderson died in 1944, the Club moved again in 1948, and it was eventually forced to shut its doors in 1951. Ironically, the success of the preservation movement, with which the club was so intimately connected, led to the decline of the bohemian lifestyle that had provided so much of the club’s vitality in the first place. In this way, the thirty-year history of the Club parallels the evolution of the French Quarter. The legacy of the New Orleans Arts and Craft Club is immense. The accomplishments of the individual artists trained and/or showcased by the club significant on their own, but the club and its artists introduced New Orleans as a whole to a modern idea of art. Perhaps most importantly, however, was the focus on the French Quarter as the axis mundi of art and culture in the city, which still resonates so strongly today. That idea and feeling, which seems so fundamental now, was by no means inevitable. It is a testament to the influence and lasting importance of the New Orleans Arts and Craft Club.