June 07, 2022

New Orleans has many musically talented families. As Grammy Award-winning piano player Jonathan Batiste put it, “music spreads like a disease.” Musicians are our heroes and our traditions are fiercely protected, making the musical family a revered institution that dates back to the 19th century and the beginning of jazz itself. In many ways, the history of these families, with names such as Dejean, Neville, Brunious, Barbarin, Batiste, Lastie, Marsalis, Jordan and Andrews, is the history of New Orleans. The future of these families is the future of the city’s culture. The Andrews family is instrumental in making New Orleans culture what it is today. One of our largest musical families, with its roots in the Tremé neighborhood, the Andrews’ sound encompasses grandfather Jessie Hill and his iconic “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” smash hit recorded in 1960. Some of his other songs were recorded by Ike and Tina Turner, Sonny and Cher, and Willie Nelson. His legacy lives on within his extended family of talented relatives spanning generations, including the currently performing Glen David Andrews and his cousins James Andrews and Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews. Exposed to the sounds of gospel, R&B, funk and jazz since early childhood, this younger generation of Andrews talent is deeply woven into the musical fabric of New Orleans culture, and the live music scene at nightclubs and festivals.

James Andrews is the grandson of Jesse Hill, the older brother and mentor of Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews, and cousin of Glen David Andrews and the late Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill. A dynamic trumpeter and vocalist, Andrews is known as “Satchmo of the Ghetto.” James Andrews has played in a number of brass bands and with Danny Barker, Dizzy Gillespie, Dr. John, and many others before launching his own band, James Andrews and the Crescent City Allstars.

After Hurricane Katrina, James Andrews was one of the first musicians to return to New Orleans following the flooding. He and his brother, “Trombone Shorty,” played at Jackson Square seventeen days after Katrina hit the area, declaring “We’re gonna rebuild this city, note by note.” James Andrews is swinging the New Orleans tradition in contemporary ways. Andrews is the real deal, a stellar trumpet player, and he’s determined to keep the flame of New Orleans Soul and R&B alive and burning in the hearts of many. If you are lucky enough to see him perform, listen for his own rendition of his grandfather’s song, “Ooh Poo Pah Doo.”

Troy and James Andrews’ cousin, Glen David Andrews is part preacher, R&B singer, jazz vocalist, and trombonist . He’s all showman, entertainer and party ringmaster. He performs with a Louis Armstrong rasp, an Al Green falsetto, a Thomas Dorsey sense of spirituals, James Brown moves with a microphone stand, Trombone Shorty licks on the trombone and a lot of manic energy. His music is versatile and he is a maestro at creating an endless party atmosphere. He parades through the crowd playing his trombone and showing off his vocal prowess, inviting audience participation with call and response, singing songs we all know and love. When he performed recently at Jazz Fest, he outdid himself with a little something for everyone. He had backup singers, a full horn section, and a top-notch band that spanned almost every genre of music. If you get a chance, be sure to catch a member of the Andrews family; they frequently perform in the neighborhoods in and near the French Quarter.

Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews is something different. A youngster in this musical dynasty, he plays a furious rock and funk brand of New Orleans brass twisted into something wholly new. In the years since Hurricane Katrina, he’s become the voice of a city determined to prove itself more than a tourist destination for party animals. Shorty grew up in Tremé, the New Orleans neighborhood that produced icons like Tuba Fats and Kermit Ruffins as well as countless brass bands. “As a kid, I would wake up and there’d be a jazz funeral while I’m walking to school,” Andrews says. “And when I come home you can find Rebirth band playing for a birthday party the same day.” When he returns home now, he’s the hometown boy that everyone knew would hit the big time. The second-youngest of six kids, his toys were the musical instruments in his home. His brother, Buster, remembers that Wynton Marsalis showed him a few lines when he was in a stroller blowing on a plastic saxophone. Many of his cousins played in brass bands, a practice common as playing baseball in his neighborhood. Sixteen years older than Troy, James served as a father figure, musically and otherwise. “Before he could walk, I had him on my back in the French Quarter, I brought him to hear everybody,” James says. “Earth, Wind and Fire, Luther Vandross, everything that I wanted to go to, but I had to watch him because my mom was going out with my dad that night … to the same show, come to find out.”

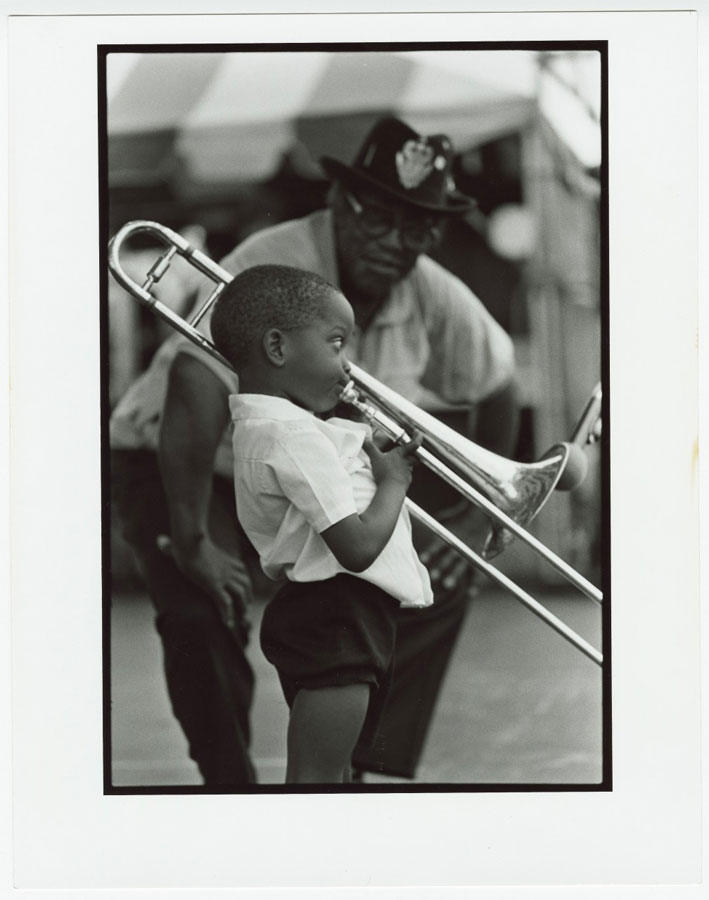

When Troy learned to play, James put him in a little suit and brought him on tour. He took him all over the world: Dubai, Paris, Turkey, Cuba. He was learning the New Orleans music that made his brother famous, but also the kind of tireless professionalism that presently allows him to play two consecutive sets before going back to the studio to record the next morning. At the age of four, Shorty appeared onstage with Bo Diddley at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. He was a bandleader by age six. In between international travel, he started his first real band, the Tiny Tunes, marching around the French Quarter for tips. He could play anything, and since no one was playing trombone, he picked it up. When he first started playing, the trombone was twice his height, hence his nickname “Trombone Shorty.”

They may have been filled with music, but the streets of the Tremé were dangerous. When Andrews was ten, his older brother, Darnell, also an accomplished trombone player, was shot and killed in the nearby Lafitte housing projects. “I guess I kind of took his spot,” Andrews says. Bands like Rebirth and Bonerama were taking traditional jazz and mixing them with funk, but few received national recognition.

After Darnell’s death, Susan Scott, a local businesswoman who was managing James at the time, took Shorty in. Her stewardship is credited with Andrews’ exposure and professionalism that kept him from the same pitfalls of his talented local contemporaries. She had a sterling reputation in the city and he still wonders what his life would have been like without his second mom and guardian angel. Unfortunately, she died of cancer in 2007. “I have a bunch of cousins, and friends, and people who grew up with me who didn’t have the same opportunity,” Shorty says. “I’ve lost a bunch of friends. Some of them are in jail, some of them made bad choices, and some of them aren’t where they should be. If I didn’t have her, I could see myself being where they are now.”

She arranged for him to audition at the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts, where he played with his future drummer and bassist. He learned standard notation and acquired a theoretical discipline that set him apart from some of his more freewheeling colleagues who learned to play on the street.

In 2004, Lenny Kravitz was looking to fill out his horn section with some New Orleans brass. He called his friend Sidney Torres, a New Orleans businessman, hotelier, and actor. Torres suggested to call on Shorty. Kravitz questioned, “How could an eighteen-year-old have soul?” But when he heard him play for the first time, he literally fell to his knees.

When Katrina hit in 2005, 19-year-old Andrews was on an international tour with Lenny Kravitz. No one knew whether the city of New Orleans would survive. Musicians lost their homes, their instruments, and their patrons, and the city’s long obsession with preserving its culture became a desperate struggle.

Andrews came back eight months later and played a show at the House of Blues to a city still just barely holding on. He had developed considerably. His time in the horn section with Kravitz had given him discipline and rock-star performance chops, and it became clear that his sound was evolving into something uniquely new.

Eventually, the city started doing something similar. It might have been stagnating before, but now it routinely appears on lists of hot cities for start-ups and investment. It’s become ground zero for educational reform. A local joke was that New Orleans had a thousand restaurants but only one menu; now dozens of restaurants new and old are realizing that the standards don’t cut it anymore. “Everything was wiped out,” Andrews says. “Everyone had to struggle to get back to a steady pace. But it’s changing in a way where we don’t want it to be the same New Orleans that it was, we want to be better in every aspect. Business, music, restaurants, whatever it may be.”

Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews’ profile has only grown since. Stars from Allen Toussaint to the Edge have sung his praises, and he’s played with U2, Green Day, and the Dave Matthews Band. He and his band, Orleans Avenue, have played to audiences as big as twenty thousand in places as far away as Australia. His 2010 album, Backatown, was #1 on the Billboard magazine’s Contemporary Jazz chart for nine weeks and got nominated for a Grammy.

Trombone Shorty & Orleans Avenue has toured across Australia, North America, Europe, Japan and Brazil. They performed on all the late-night television shows and at the White House twice. They have recorded with Galactic, Eric Clapton, and Dr. John and toured with the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the Foo Fighters, among many others. In spite of his stardom, Shorty has lived in New Orleans all his life.

As a way to preserve the city’s musical culture and inspire future generations of musicians, Troy Andrews established the Trombone Shorty Foundation and its flagship music education program, the Trombone Shorty Academy. The Academy supports musically inclined youth, providing high school musicians with mentorships and lessons in musical performance ranging from traditional jazz to hip-hop. The Fredman Music Business Institute, another program within the Trombone Shorty Foundation, delivers practical business instruction from music industry leaders. Creating and nurturing future leaders in hospitality, music, arts and culture will help ensure the sights, sounds, and tastes of New Orleans will remain well into the next century. For a city that’s been setting the table, shaking the cocktails and creating the beat for 300 years, it’s the only way to go.

James Andrews is the grandson of Jesse Hill, the older brother and mentor of Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews, and cousin of Glen David Andrews and the late Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill. A dynamic trumpeter and vocalist, Andrews is known as “Satchmo of the Ghetto.” James Andrews has played in a number of brass bands and with Danny Barker, Dizzy Gillespie, Dr. John, and many others before launching his own band, James Andrews and the Crescent City Allstars.

After Hurricane Katrina, James Andrews was one of the first musicians to return to New Orleans following the flooding. He and his brother, “Trombone Shorty,” played at Jackson Square seventeen days after Katrina hit the area, declaring “We’re gonna rebuild this city, note by note.” James Andrews is swinging the New Orleans tradition in contemporary ways. Andrews is the real deal, a stellar trumpet player, and he’s determined to keep the flame of New Orleans Soul and R&B alive and burning in the hearts of many. If you are lucky enough to see him perform, listen for his own rendition of his grandfather’s song, “Ooh Poo Pah Doo.”

Troy and James Andrews’ cousin, Glen David Andrews is part preacher, R&B singer, jazz vocalist, and trombonist . He’s all showman, entertainer and party ringmaster. He performs with a Louis Armstrong rasp, an Al Green falsetto, a Thomas Dorsey sense of spirituals, James Brown moves with a microphone stand, Trombone Shorty licks on the trombone and a lot of manic energy. His music is versatile and he is a maestro at creating an endless party atmosphere. He parades through the crowd playing his trombone and showing off his vocal prowess, inviting audience participation with call and response, singing songs we all know and love. When he performed recently at Jazz Fest, he outdid himself with a little something for everyone. He had backup singers, a full horn section, and a top-notch band that spanned almost every genre of music. If you get a chance, be sure to catch a member of the Andrews family; they frequently perform in the neighborhoods in and near the French Quarter.

Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews is something different. A youngster in this musical dynasty, he plays a furious rock and funk brand of New Orleans brass twisted into something wholly new. In the years since Hurricane Katrina, he’s become the voice of a city determined to prove itself more than a tourist destination for party animals. Shorty grew up in Tremé, the New Orleans neighborhood that produced icons like Tuba Fats and Kermit Ruffins as well as countless brass bands. “As a kid, I would wake up and there’d be a jazz funeral while I’m walking to school,” Andrews says. “And when I come home you can find Rebirth band playing for a birthday party the same day.” When he returns home now, he’s the hometown boy that everyone knew would hit the big time. The second-youngest of six kids, his toys were the musical instruments in his home. His brother, Buster, remembers that Wynton Marsalis showed him a few lines when he was in a stroller blowing on a plastic saxophone. Many of his cousins played in brass bands, a practice common as playing baseball in his neighborhood. Sixteen years older than Troy, James served as a father figure, musically and otherwise. “Before he could walk, I had him on my back in the French Quarter, I brought him to hear everybody,” James says. “Earth, Wind and Fire, Luther Vandross, everything that I wanted to go to, but I had to watch him because my mom was going out with my dad that night … to the same show, come to find out.”

When Troy learned to play, James put him in a little suit and brought him on tour. He took him all over the world: Dubai, Paris, Turkey, Cuba. He was learning the New Orleans music that made his brother famous, but also the kind of tireless professionalism that presently allows him to play two consecutive sets before going back to the studio to record the next morning. At the age of four, Shorty appeared onstage with Bo Diddley at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. He was a bandleader by age six. In between international travel, he started his first real band, the Tiny Tunes, marching around the French Quarter for tips. He could play anything, and since no one was playing trombone, he picked it up. When he first started playing, the trombone was twice his height, hence his nickname “Trombone Shorty.”

They may have been filled with music, but the streets of the Tremé were dangerous. When Andrews was ten, his older brother, Darnell, also an accomplished trombone player, was shot and killed in the nearby Lafitte housing projects. “I guess I kind of took his spot,” Andrews says. Bands like Rebirth and Bonerama were taking traditional jazz and mixing them with funk, but few received national recognition.

After Darnell’s death, Susan Scott, a local businesswoman who was managing James at the time, took Shorty in. Her stewardship is credited with Andrews’ exposure and professionalism that kept him from the same pitfalls of his talented local contemporaries. She had a sterling reputation in the city and he still wonders what his life would have been like without his second mom and guardian angel. Unfortunately, she died of cancer in 2007. “I have a bunch of cousins, and friends, and people who grew up with me who didn’t have the same opportunity,” Shorty says. “I’ve lost a bunch of friends. Some of them are in jail, some of them made bad choices, and some of them aren’t where they should be. If I didn’t have her, I could see myself being where they are now.”

She arranged for him to audition at the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts, where he played with his future drummer and bassist. He learned standard notation and acquired a theoretical discipline that set him apart from some of his more freewheeling colleagues who learned to play on the street.

In 2004, Lenny Kravitz was looking to fill out his horn section with some New Orleans brass. He called his friend Sidney Torres, a New Orleans businessman, hotelier, and actor. Torres suggested to call on Shorty. Kravitz questioned, “How could an eighteen-year-old have soul?” But when he heard him play for the first time, he literally fell to his knees.

When Katrina hit in 2005, 19-year-old Andrews was on an international tour with Lenny Kravitz. No one knew whether the city of New Orleans would survive. Musicians lost their homes, their instruments, and their patrons, and the city’s long obsession with preserving its culture became a desperate struggle.

Andrews came back eight months later and played a show at the House of Blues to a city still just barely holding on. He had developed considerably. His time in the horn section with Kravitz had given him discipline and rock-star performance chops, and it became clear that his sound was evolving into something uniquely new.

Eventually, the city started doing something similar. It might have been stagnating before, but now it routinely appears on lists of hot cities for start-ups and investment. It’s become ground zero for educational reform. A local joke was that New Orleans had a thousand restaurants but only one menu; now dozens of restaurants new and old are realizing that the standards don’t cut it anymore. “Everything was wiped out,” Andrews says. “Everyone had to struggle to get back to a steady pace. But it’s changing in a way where we don’t want it to be the same New Orleans that it was, we want to be better in every aspect. Business, music, restaurants, whatever it may be.”

Troy “Trombone Shorty” Andrews’ profile has only grown since. Stars from Allen Toussaint to the Edge have sung his praises, and he’s played with U2, Green Day, and the Dave Matthews Band. He and his band, Orleans Avenue, have played to audiences as big as twenty thousand in places as far away as Australia. His 2010 album, Backatown, was #1 on the Billboard magazine’s Contemporary Jazz chart for nine weeks and got nominated for a Grammy.

Trombone Shorty & Orleans Avenue has toured across Australia, North America, Europe, Japan and Brazil. They performed on all the late-night television shows and at the White House twice. They have recorded with Galactic, Eric Clapton, and Dr. John and toured with the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the Foo Fighters, among many others. In spite of his stardom, Shorty has lived in New Orleans all his life.

As a way to preserve the city’s musical culture and inspire future generations of musicians, Troy Andrews established the Trombone Shorty Foundation and its flagship music education program, the Trombone Shorty Academy. The Academy supports musically inclined youth, providing high school musicians with mentorships and lessons in musical performance ranging from traditional jazz to hip-hop. The Fredman Music Business Institute, another program within the Trombone Shorty Foundation, delivers practical business instruction from music industry leaders. Creating and nurturing future leaders in hospitality, music, arts and culture will help ensure the sights, sounds, and tastes of New Orleans will remain well into the next century. For a city that’s been setting the table, shaking the cocktails and creating the beat for 300 years, it’s the only way to go.