October 31, 2016

These days, New Orleans is bursting at the seams — just as it was 200 years ago.

Eleven years after the physical devastation and population decline in the aftermath of 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, the city is filled with Millennials, opening new businesses, frequenting hundreds of new cafes and bars, and devouring art in galleries in both the Vieux Carre and surrounding neighborhoods.

In 2018 as the city prepares to celebrate the 300th anniversary of its founding, the essence of New Orleans as a network of individual neighborhoods, each with a distinct cultural and artistic identity, has never been stronger.

A fine place to begin a tour of the city’s artistic diversity is Jackson Square (originally Place d’Armes), the heart of the original city. Have a cup of cafe au lait (coffee and chicory, with steaming hot milk) and a trio of beignets (light, puffy fried “doughnuts”) at the noted Cafe du Monde, just across Decatur Street.

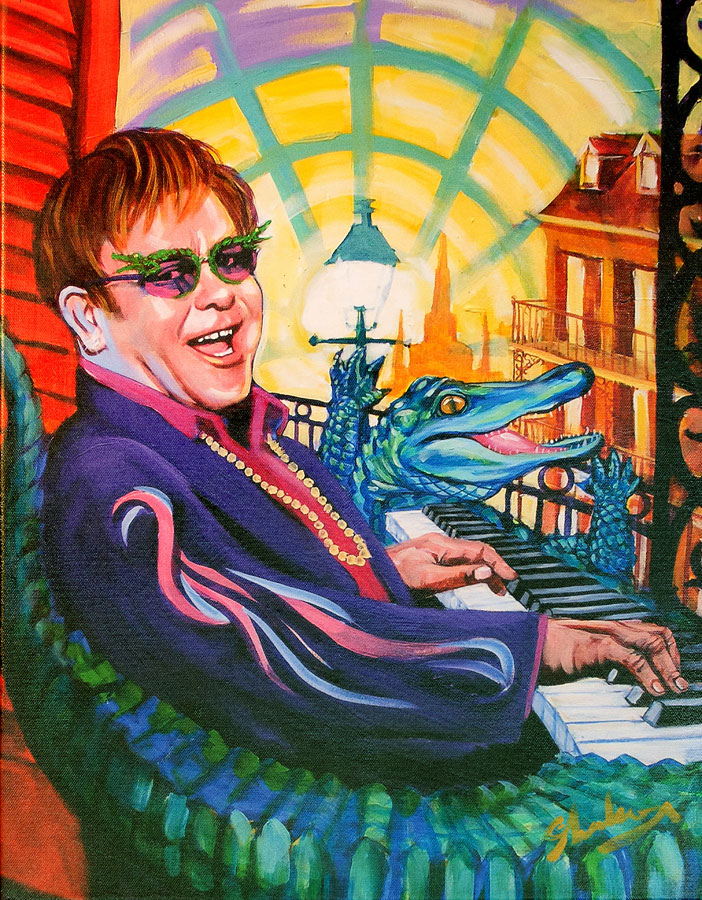

Artistic treasures await just up the street at Gallery Cayenne (702 Decatur St.), where a dizzying display of color greets passersby in portraits of celebrities and New Orleans scenes by a dynamic artist known simply as Shakor. But it’s inside, in his low-ceilinged gallery, under the cascade of steps that lead over the seawall to the riverfront, that the artist’s personality shines forth, along with amusing and incisive anecdotes about his creative life.

“My momma discovered my talent when I was four years old,” Shakor told a recent visitor to the gallery. “I guess you might say it was some sort of accident. My brother was nine, and he had this comic book of The Flash — you remember that costume, mostly red and yellow. Well, he was drawing that, and I followed what he was doing, and my momma came into the room and saw I was better.

“Let me tell you,” he continued. “When I first stuck my hand in that tempera paint and set my mind to do some painting, when I smelled that paint, man, I was hooked.”

Visits to New York museums led to classes at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. A photograph of Shakor, standing by his first still-life painting, created in the class when he was just eight, hangs prominently behind the artist’s desk.

“That was my first painting, and you can tell I ran out of red paint in the upper right corner. I remember I accused another student of using too much of the red, not leaving enough for me. But now, I guess, it was just that I didn't know to thin out the paint enough.”

He attended New York’s prestigious High School of Art and Design, by which time he had become adept at mixing color; and he later turned down scholarships to Boston University and the career-making Rhode Island School of Design to accept a scholarship at Manhattan’s Cooper Union, which he felt offered the finest training in art.

After six years as a graphic designer in Los Angeles, he moved to New Orleans in 1990, where his degrees were meaningless. He became a housekeeper at a hospital, then specialized in maintaining stone and marble floors in hotels. He loaded frozen chicken on boats destined for foreign lands, and retained his dignity by deciding, when an inner voice spoke to him, that he would be “the best frozen chicken loader there ever was.”

And then he landed the job of painting a brilliantly-hued mural at New Orleans’ Ashe Cultural Center. It wasn’t long before he decided to open his own gallery and realize a decades-long dream of sustaining himself as an artist. Today, the brilliant reds and yellows of The Flash’s costume are still prominent in his paintings.

One customer was drawn in by Shakor’s portrait of Redd Foxx outside the entrance to the gallery. “I don’t know how many times I watched every episode of that show when I was a girl,” she said, proffering a credit card to purchase a smaller giclee print of the portrait.

Another customer squealed as she discovered a dynamic portrait of Elvis, which she declared would soon hold a place of honor in her Dallas mega mansion.

But Shakor’s true talent, a reflection of his studies of the great painters, is in reinventions of masterworks, including Picasso’s iconic Guernica, a diorama of the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

“I used Picasso’s structure,” he said with a grin, “but I wanted to make it all lighter, so I used Mardi Gras and New Orleans imagery instead.” In place of Picasso’s twisting, grimacing horse, Shakor makes an albino alligator the centerpiece of the work, and the Rex parade’s Boeuf Gras replaces Picasso’s bull’s head. A hand offers a coveted Zulu coconut instead of a lamp; and a Cubist catfish, Carnival revelers and make-believe royalty surround a stylization of Picasso’s features. In New Orleans French parlance, it’s a Chef d’oeuvre, or masterpiece, in its own right.

Also on display is a portrait of a young girl who wished to be portrayed as a dancer, and a trio of a mother and two daughters, one deceased. In each case, Shakor captures the spirit of the individual with a light touch.

When another visitor asked Shakor if he is self-taught, the 60-year-old artist replied, “If you have a God-given gift, you can't just say that someone taught you how to use it. Determination is what develops your skills, and you have to share your gift.”

A walk down Royal Street will continue your “artistic tour” of the city and take you to the Central Business District, just across Canal Street. Established in the late 18th century as the Faubourg Ste.-Marie, the area accommodated Americans who flocked to the city after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, much as young people are currently resettling in New Orleans.

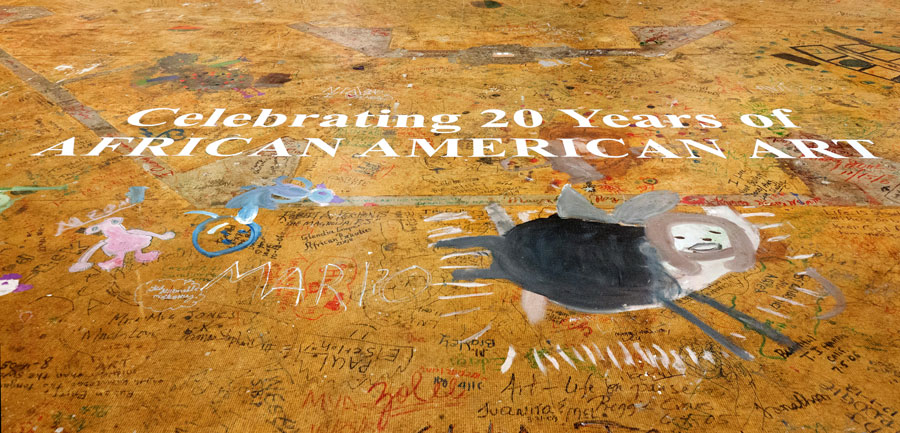

Stella Jones Gallery, located in Place St. Charles at 201 St. Charles Ave., is one of the most renowned galleries featuring the work of African-American artists in the country. Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, the gallery reflects the tastes of owner/founder Stella Jones, a Houston native who became a physician before turning her love of art into a mission to bring attention to an important subset of American art.

As an arts activist, Jones has participated in national and international projects that use art to benefit those in need. A decade ago, she brought Oprah Winfrey’s project to help Rwandan women to New Orleans. Local women, working in her gallery, made 7,000 bracelets and 2,500 necklaces, all sold to aid women in that African country.

Currently on view are works by Samella Lewis, a noted artist and prominent art historian who at 92 still writes and paints, and E.J. Montgomery, 84, whose career as an artist spanned periods as a sculptor, fabric artist, and now, increasingly, printmaker. Lewis’s work is primarily figurative, while “E.J.” - as she’s fondly known - has always dealt in abstraction. The art of both women reflects their historical research and writings about art.

Louisiana bayou folk artist Alvin Batiste adds a touch of whimsy to the gallery with small watercolors on almost any subject having to do with rural life in Louisiana. A middle-aged man who likes to think young, Batiste is seeing new interest in his work — with curators from East Coast museums, including the Smithsonian, purchasing his art.

Crossing Canal Street back into the French Quarter, dog lovers will encounter an engaging shop in Adorn Gallery, 610 Royal St.

After Hurricane Katrina, photographer Robin Bell and her business partner, Jennie Alexndry, spotted Shiloh — the famous “Swamp Dog” — while borrowing an old pirogue to display in a local wooden boat festival. The duo specializes in “whimsical photographs of dogs featured in unexpected places, including famous New Orleans restaurants and bars.”

Swamp Dog is the star of such delightful images as “Hair of the Dog,” depicting the enigmatic canine sucking a daiquiri through a straw in historic Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, a celebrated French Quarter watering hole.

A favorite image in the Swamp Dog and Friends section of the gallery is “Love is Patient,” a hound in the cab of a rundown pickup truck on Laurel Valley Plantation, near Thibodaux, La. Adventurous visitors with a little extra time can schedule a private shoot with their pooch in the same venue.

After nightfall, a visit to the Frenchmen Art Market, 619 Frenchmen St., is almost obligatory. Located across Esplanade Avenue, at the lower end of Royal Street, the market is just a few steps away on Frenchman Street, in what is known as Faubourg Marigny. This early suburb was laid out in the first decade of the 19th century by a wealthy French landowner, Bernard de Marigny, and is a busy hive of restaurants, music clubs and art galleries. Open Thursday - Monday, roughly from dusk to around midnight or 1 a.m., the market is a wide open space, with sofas made from claw-footed bathtubs and other enticing spots to rest your feet after a day of exploring art galleries.

On a recent evening, artists included Sierra Kozman, who creates engaging posters of flora and fauna — including marine iguanas native to the Galapagos Islands. An avowed environmentalist, Kozman prints on “beautiful cover-weight paper made in a factory that runs on hydroelectric steam.”

Across the way, photography of the suffering after Katrina highlights a display set up by Marrus, a New York transplant. A recurrent theme in her delicate pen-and-ink-and-oil paintings is houses with little wings “that can fly over the city in a disaster.”

Wood-carver and craftsman Josh Wascome jokes that he provides “a tree removal service, just by actively looking for fallen trees along the roadside.” Solid bits of wood become handsome cutting boards, while Wascome’s best-selling turned bowls are crafted from wood with unique imperfections that give the finished piece “character.”

End your tour with dinner at a Frenchmen Street restaurant, where it’s easy to get in the spirit wearing a fancy headpiece or elaborately-decorated comb from Gypsy Junk. Owner Chloe Rose, her resplendent red hair drawing as much attention as her exquisite tonsorial adornments, confesses a fascination with the Edwardian Age and the 1920s, creating unique pieces that are “a little bit of old, and a little bit of me.”

In just one day, you will have experienced not just the French Quarter, but also the first suburbs of the historic city. And the art you’ll discover will remind you of the diversity and joie de vivre of this culturally-rich city.

Eleven years after the physical devastation and population decline in the aftermath of 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, the city is filled with Millennials, opening new businesses, frequenting hundreds of new cafes and bars, and devouring art in galleries in both the Vieux Carre and surrounding neighborhoods.

In 2018 as the city prepares to celebrate the 300th anniversary of its founding, the essence of New Orleans as a network of individual neighborhoods, each with a distinct cultural and artistic identity, has never been stronger.

A fine place to begin a tour of the city’s artistic diversity is Jackson Square (originally Place d’Armes), the heart of the original city. Have a cup of cafe au lait (coffee and chicory, with steaming hot milk) and a trio of beignets (light, puffy fried “doughnuts”) at the noted Cafe du Monde, just across Decatur Street.

Artistic treasures await just up the street at Gallery Cayenne (702 Decatur St.), where a dizzying display of color greets passersby in portraits of celebrities and New Orleans scenes by a dynamic artist known simply as Shakor. But it’s inside, in his low-ceilinged gallery, under the cascade of steps that lead over the seawall to the riverfront, that the artist’s personality shines forth, along with amusing and incisive anecdotes about his creative life.

“My momma discovered my talent when I was four years old,” Shakor told a recent visitor to the gallery. “I guess you might say it was some sort of accident. My brother was nine, and he had this comic book of The Flash — you remember that costume, mostly red and yellow. Well, he was drawing that, and I followed what he was doing, and my momma came into the room and saw I was better.

“Let me tell you,” he continued. “When I first stuck my hand in that tempera paint and set my mind to do some painting, when I smelled that paint, man, I was hooked.”

Visits to New York museums led to classes at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. A photograph of Shakor, standing by his first still-life painting, created in the class when he was just eight, hangs prominently behind the artist’s desk.

“That was my first painting, and you can tell I ran out of red paint in the upper right corner. I remember I accused another student of using too much of the red, not leaving enough for me. But now, I guess, it was just that I didn't know to thin out the paint enough.”

He attended New York’s prestigious High School of Art and Design, by which time he had become adept at mixing color; and he later turned down scholarships to Boston University and the career-making Rhode Island School of Design to accept a scholarship at Manhattan’s Cooper Union, which he felt offered the finest training in art.

After six years as a graphic designer in Los Angeles, he moved to New Orleans in 1990, where his degrees were meaningless. He became a housekeeper at a hospital, then specialized in maintaining stone and marble floors in hotels. He loaded frozen chicken on boats destined for foreign lands, and retained his dignity by deciding, when an inner voice spoke to him, that he would be “the best frozen chicken loader there ever was.”

And then he landed the job of painting a brilliantly-hued mural at New Orleans’ Ashe Cultural Center. It wasn’t long before he decided to open his own gallery and realize a decades-long dream of sustaining himself as an artist. Today, the brilliant reds and yellows of The Flash’s costume are still prominent in his paintings.

One customer was drawn in by Shakor’s portrait of Redd Foxx outside the entrance to the gallery. “I don’t know how many times I watched every episode of that show when I was a girl,” she said, proffering a credit card to purchase a smaller giclee print of the portrait.

Another customer squealed as she discovered a dynamic portrait of Elvis, which she declared would soon hold a place of honor in her Dallas mega mansion.

But Shakor’s true talent, a reflection of his studies of the great painters, is in reinventions of masterworks, including Picasso’s iconic Guernica, a diorama of the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

“I used Picasso’s structure,” he said with a grin, “but I wanted to make it all lighter, so I used Mardi Gras and New Orleans imagery instead.” In place of Picasso’s twisting, grimacing horse, Shakor makes an albino alligator the centerpiece of the work, and the Rex parade’s Boeuf Gras replaces Picasso’s bull’s head. A hand offers a coveted Zulu coconut instead of a lamp; and a Cubist catfish, Carnival revelers and make-believe royalty surround a stylization of Picasso’s features. In New Orleans French parlance, it’s a Chef d’oeuvre, or masterpiece, in its own right.

Also on display is a portrait of a young girl who wished to be portrayed as a dancer, and a trio of a mother and two daughters, one deceased. In each case, Shakor captures the spirit of the individual with a light touch.

When another visitor asked Shakor if he is self-taught, the 60-year-old artist replied, “If you have a God-given gift, you can't just say that someone taught you how to use it. Determination is what develops your skills, and you have to share your gift.”

A walk down Royal Street will continue your “artistic tour” of the city and take you to the Central Business District, just across Canal Street. Established in the late 18th century as the Faubourg Ste.-Marie, the area accommodated Americans who flocked to the city after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, much as young people are currently resettling in New Orleans.

Stella Jones Gallery, located in Place St. Charles at 201 St. Charles Ave., is one of the most renowned galleries featuring the work of African-American artists in the country. Celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, the gallery reflects the tastes of owner/founder Stella Jones, a Houston native who became a physician before turning her love of art into a mission to bring attention to an important subset of American art.

As an arts activist, Jones has participated in national and international projects that use art to benefit those in need. A decade ago, she brought Oprah Winfrey’s project to help Rwandan women to New Orleans. Local women, working in her gallery, made 7,000 bracelets and 2,500 necklaces, all sold to aid women in that African country.

Currently on view are works by Samella Lewis, a noted artist and prominent art historian who at 92 still writes and paints, and E.J. Montgomery, 84, whose career as an artist spanned periods as a sculptor, fabric artist, and now, increasingly, printmaker. Lewis’s work is primarily figurative, while “E.J.” - as she’s fondly known - has always dealt in abstraction. The art of both women reflects their historical research and writings about art.

Louisiana bayou folk artist Alvin Batiste adds a touch of whimsy to the gallery with small watercolors on almost any subject having to do with rural life in Louisiana. A middle-aged man who likes to think young, Batiste is seeing new interest in his work — with curators from East Coast museums, including the Smithsonian, purchasing his art.

Crossing Canal Street back into the French Quarter, dog lovers will encounter an engaging shop in Adorn Gallery, 610 Royal St.

After Hurricane Katrina, photographer Robin Bell and her business partner, Jennie Alexndry, spotted Shiloh — the famous “Swamp Dog” — while borrowing an old pirogue to display in a local wooden boat festival. The duo specializes in “whimsical photographs of dogs featured in unexpected places, including famous New Orleans restaurants and bars.”

Swamp Dog is the star of such delightful images as “Hair of the Dog,” depicting the enigmatic canine sucking a daiquiri through a straw in historic Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop, a celebrated French Quarter watering hole.

A favorite image in the Swamp Dog and Friends section of the gallery is “Love is Patient,” a hound in the cab of a rundown pickup truck on Laurel Valley Plantation, near Thibodaux, La. Adventurous visitors with a little extra time can schedule a private shoot with their pooch in the same venue.

After nightfall, a visit to the Frenchmen Art Market, 619 Frenchmen St., is almost obligatory. Located across Esplanade Avenue, at the lower end of Royal Street, the market is just a few steps away on Frenchman Street, in what is known as Faubourg Marigny. This early suburb was laid out in the first decade of the 19th century by a wealthy French landowner, Bernard de Marigny, and is a busy hive of restaurants, music clubs and art galleries. Open Thursday - Monday, roughly from dusk to around midnight or 1 a.m., the market is a wide open space, with sofas made from claw-footed bathtubs and other enticing spots to rest your feet after a day of exploring art galleries.

On a recent evening, artists included Sierra Kozman, who creates engaging posters of flora and fauna — including marine iguanas native to the Galapagos Islands. An avowed environmentalist, Kozman prints on “beautiful cover-weight paper made in a factory that runs on hydroelectric steam.”

Across the way, photography of the suffering after Katrina highlights a display set up by Marrus, a New York transplant. A recurrent theme in her delicate pen-and-ink-and-oil paintings is houses with little wings “that can fly over the city in a disaster.”

Wood-carver and craftsman Josh Wascome jokes that he provides “a tree removal service, just by actively looking for fallen trees along the roadside.” Solid bits of wood become handsome cutting boards, while Wascome’s best-selling turned bowls are crafted from wood with unique imperfections that give the finished piece “character.”

End your tour with dinner at a Frenchmen Street restaurant, where it’s easy to get in the spirit wearing a fancy headpiece or elaborately-decorated comb from Gypsy Junk. Owner Chloe Rose, her resplendent red hair drawing as much attention as her exquisite tonsorial adornments, confesses a fascination with the Edwardian Age and the 1920s, creating unique pieces that are “a little bit of old, and a little bit of me.”

In just one day, you will have experienced not just the French Quarter, but also the first suburbs of the historic city. And the art you’ll discover will remind you of the diversity and joie de vivre of this culturally-rich city.