September 06, 2022

Knowing your limitations can be one of the smartest things you can do for yourself, and I have always known mine. Paying attention to them can be a different story. But knowing something and living something are often two vastly different things.

If you listen to your limitations, you just might find yourself keeping the training wheels on your first two-wheel bike on far longer than you ever needed them. Let your limitations take control, and you’ll find yourself snuggled safely in your nest while the world and all its grand opportunities pass right by you without a second glance.

My dad and his brother Big Lou—I called him Big Lou because Louis was taller than my dad, older than my dad, and had a son called Lil Lou—used to tell me, “Life isn’t gonna wait for you, Ryan. You gotta realize there isn’t much here for you in this little town.” They were right, but no matter how frustrated I got with small town life, and no matter how curious I was about the places with tall buildings and palm trees, my limitations kept me stuck right where I was. “You’re never going to get out of this town,” I would say to myself, “just get used it.”

There is beauty in seeing others overcome limitations, seeing them leaping into a world of the unknown by choice. However, it’s when people are forced to overcome their limitations and leap into the unknown that we see inspiration and enlightenment at its finest. Choosing a path is one thing—having a path chosen for you is a paintbrush of a vastly different color.

Artist and barber Micah Nickens is one of those people forced to face his limitations head-on. His recent installation, at The Gallery in The Ace Hotel on Carondelet Street, is a visual walking tour of a person who knows their limitations and refusing to settle for them. After a nearly fatal Vespa accident on St. Claude Avenue put him into a coma with severe brain trauma, Nickens had to battle both physical and mental rehabilitation. If that isn’t inspiring enough, he decided after a simple suggestion that he should try painting or creating as part of his rehabilitation. As if he had been doing it all his life, Nickens ignored his limitations, and at the wise advice of a friend, started painting. His friend told him to not look at other artwork, not to do research, not to learn technique—just get some paint and a canvas and create. No advice could have been wiser to nurture Nickens’ soul or the artwork he was about to create.

As he started a journey through the unknown realm of healing, he endeavored to create physical things in a realm he had never entered either: the realm of painting. Without even knowing it, Nickens set out on a plan to create a road map to his healing with his own hands, knowing his limitations, but refusing to live by them. His innocent and untainted knowledge of painting would allow him to refuse conventional ideas about what his work should look like, and let it be exactly what he needed it to be: mediation, medicine, healing. Whatever it meant to him, his work got the blessing of having a creator untarnished by the idea of creating for any other purpose but to heal themselves. In Micah Nickens’ own words, there was no “right” placed on his work.

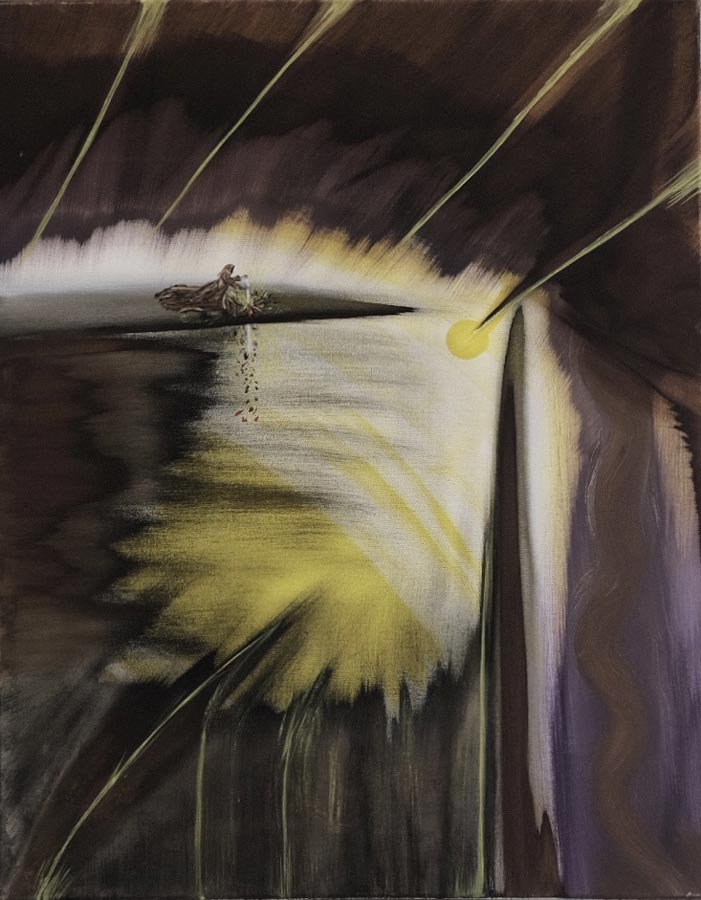

Organically, his imagery began to develop and take the life force from his hands, sending that back into him as he delved deeper into painting. His images are often smooth, and flow like water but with an abrupt ending where you are almost saddened that you cannot keep flowing along so smoothly or calmly. You might find yourself taken in by a certain color or texture only to find yourself noticing an image hidden deep inside the texture Nickens intended to place there. We are free of symbolism for the sake of statement and allowed to just enjoy his self-portrait that, for some reason, has large bird painted into it. Why a bird? Well, that’s just it; there’s no “why a bird?” It’s just there because it grew there. It developed there on its own without purpose except to bring Nickens one step farther along on his journey, with no deliberate message to us on the part of the artist.

Which brings us to “Why not a bird?” as a valid question. Characters come in and out of his paintings, and the overall feeling of an ethereal, dreamlike openness never leaves you as you venture forward from one image to the next. “It’s like medicine,” he said as I sat listening to him try to explain what he does and why he does it. The beauty of it, again, it that he didn’t need to, and I didn’t need him to. Why he did this or that, or why this was red instead of blue, is simply accepted and inherently understood, before he was speaking about it.

And there is good reason for that: As we focus on the process helping to heal Nickens, we cannot overlook that art is being created right alongside his growth. His healing is spawning a physical thing that lives in our world with no restrictions, no rules, no reason, no demands, and most importantly no “weight.” You almost never see that in today’s world, and his paintings are as important as his healing, just for that reason.

Nickens’ work can be seen through September at The Ace Hotel Art Gallery. This is the same hotel where he is part owner of Parker Barber, a super-sophisticated, butched-up, sexy place to get haircut and your good looks on!

Learning from your limitations doesn’t have to be an exclusively inner battle. Choosing to live beyond your limitations can give you the strength to take on battles for your community and the city you live and love so much. Jackson Square artist Reggie Ford is a living example of that. Keeping his limitations in check, he sells his dynamic paintings daily at the St. Ann Street corner of Jackson Square. Reggie almost single-handedly supports the rehabilitation of New Orleans’ Lincoln Beach. Developed before segregation, Lincoln Beach was a place for African-Americans to experience an aspect of the world in safe environment. It was the “Black folks’ Pontchartrain Beach,” as Ford likes to explain. As time went on and African-Americans were allowed to attend the same beaches as white Americans, the need for places like Lincoln Beach declined. Couple that with a few hurricanes and our regular environmental abuses, and Lincoln Beach fell to ruin. Ford has taken on the task of bringing Lincoln Beach back to its glory days, and for no other reason than to breathe life back into a place that had been forgotten and neglected.

Reggie’s work is beaming with his love for our great city. He gets why we love New Orleans, what New Orleans means to the rest of the world, and is truly one of us. Deep colors mix with an urban grit around our city’s most iconic buildings and landmarks. Finish that off with a touch of whimsy, and Ford has created imagery that truly represents our city. It looks like our city, feels like our city, and even sounds like our city. The volume changes from painting to painting as does the song and the genre of music that comes to mind. Smart placement of images convinces me that Ford is deliberately positioning his characters on stage as a director would, freezing them in time, and capturing a different moment for each of us. His work is among the cleanest and historic yet gritty and modern images being painted today. I particularly love his incorporation of stick figures. The clean, smooth lines that dance in Second Lines make me laugh even harder at people who exclaim “I can’t even draw a stick figure” as they parade from gallery to gallery. His works are, in themselves, art.

Eventually, I made it out of my small town, having mustered up the courage to venture to many of the beautiful places the world has to offer. But it wasn’t easy. You see, I found a way to cheat my limitations: I stayed close to one thing I tried to escape, yet I drew strength from that same thing as I ventured out. I returned to my small town when I needed a little safety. Limitations are simply the shackles you place on yourself. Knowing their presence is the one and only thing you need to shake them off and live the life you always knew you could. It’s as easy and as hard as that, and that makes the journey ever more rewarding.

If you listen to your limitations, you just might find yourself keeping the training wheels on your first two-wheel bike on far longer than you ever needed them. Let your limitations take control, and you’ll find yourself snuggled safely in your nest while the world and all its grand opportunities pass right by you without a second glance.

My dad and his brother Big Lou—I called him Big Lou because Louis was taller than my dad, older than my dad, and had a son called Lil Lou—used to tell me, “Life isn’t gonna wait for you, Ryan. You gotta realize there isn’t much here for you in this little town.” They were right, but no matter how frustrated I got with small town life, and no matter how curious I was about the places with tall buildings and palm trees, my limitations kept me stuck right where I was. “You’re never going to get out of this town,” I would say to myself, “just get used it.”

There is beauty in seeing others overcome limitations, seeing them leaping into a world of the unknown by choice. However, it’s when people are forced to overcome their limitations and leap into the unknown that we see inspiration and enlightenment at its finest. Choosing a path is one thing—having a path chosen for you is a paintbrush of a vastly different color.

Artist and barber Micah Nickens is one of those people forced to face his limitations head-on. His recent installation, at The Gallery in The Ace Hotel on Carondelet Street, is a visual walking tour of a person who knows their limitations and refusing to settle for them. After a nearly fatal Vespa accident on St. Claude Avenue put him into a coma with severe brain trauma, Nickens had to battle both physical and mental rehabilitation. If that isn’t inspiring enough, he decided after a simple suggestion that he should try painting or creating as part of his rehabilitation. As if he had been doing it all his life, Nickens ignored his limitations, and at the wise advice of a friend, started painting. His friend told him to not look at other artwork, not to do research, not to learn technique—just get some paint and a canvas and create. No advice could have been wiser to nurture Nickens’ soul or the artwork he was about to create.

As he started a journey through the unknown realm of healing, he endeavored to create physical things in a realm he had never entered either: the realm of painting. Without even knowing it, Nickens set out on a plan to create a road map to his healing with his own hands, knowing his limitations, but refusing to live by them. His innocent and untainted knowledge of painting would allow him to refuse conventional ideas about what his work should look like, and let it be exactly what he needed it to be: mediation, medicine, healing. Whatever it meant to him, his work got the blessing of having a creator untarnished by the idea of creating for any other purpose but to heal themselves. In Micah Nickens’ own words, there was no “right” placed on his work.

Organically, his imagery began to develop and take the life force from his hands, sending that back into him as he delved deeper into painting. His images are often smooth, and flow like water but with an abrupt ending where you are almost saddened that you cannot keep flowing along so smoothly or calmly. You might find yourself taken in by a certain color or texture only to find yourself noticing an image hidden deep inside the texture Nickens intended to place there. We are free of symbolism for the sake of statement and allowed to just enjoy his self-portrait that, for some reason, has large bird painted into it. Why a bird? Well, that’s just it; there’s no “why a bird?” It’s just there because it grew there. It developed there on its own without purpose except to bring Nickens one step farther along on his journey, with no deliberate message to us on the part of the artist.

Which brings us to “Why not a bird?” as a valid question. Characters come in and out of his paintings, and the overall feeling of an ethereal, dreamlike openness never leaves you as you venture forward from one image to the next. “It’s like medicine,” he said as I sat listening to him try to explain what he does and why he does it. The beauty of it, again, it that he didn’t need to, and I didn’t need him to. Why he did this or that, or why this was red instead of blue, is simply accepted and inherently understood, before he was speaking about it.

And there is good reason for that: As we focus on the process helping to heal Nickens, we cannot overlook that art is being created right alongside his growth. His healing is spawning a physical thing that lives in our world with no restrictions, no rules, no reason, no demands, and most importantly no “weight.” You almost never see that in today’s world, and his paintings are as important as his healing, just for that reason.

Nickens’ work can be seen through September at The Ace Hotel Art Gallery. This is the same hotel where he is part owner of Parker Barber, a super-sophisticated, butched-up, sexy place to get haircut and your good looks on!

Learning from your limitations doesn’t have to be an exclusively inner battle. Choosing to live beyond your limitations can give you the strength to take on battles for your community and the city you live and love so much. Jackson Square artist Reggie Ford is a living example of that. Keeping his limitations in check, he sells his dynamic paintings daily at the St. Ann Street corner of Jackson Square. Reggie almost single-handedly supports the rehabilitation of New Orleans’ Lincoln Beach. Developed before segregation, Lincoln Beach was a place for African-Americans to experience an aspect of the world in safe environment. It was the “Black folks’ Pontchartrain Beach,” as Ford likes to explain. As time went on and African-Americans were allowed to attend the same beaches as white Americans, the need for places like Lincoln Beach declined. Couple that with a few hurricanes and our regular environmental abuses, and Lincoln Beach fell to ruin. Ford has taken on the task of bringing Lincoln Beach back to its glory days, and for no other reason than to breathe life back into a place that had been forgotten and neglected.

Reggie’s work is beaming with his love for our great city. He gets why we love New Orleans, what New Orleans means to the rest of the world, and is truly one of us. Deep colors mix with an urban grit around our city’s most iconic buildings and landmarks. Finish that off with a touch of whimsy, and Ford has created imagery that truly represents our city. It looks like our city, feels like our city, and even sounds like our city. The volume changes from painting to painting as does the song and the genre of music that comes to mind. Smart placement of images convinces me that Ford is deliberately positioning his characters on stage as a director would, freezing them in time, and capturing a different moment for each of us. His work is among the cleanest and historic yet gritty and modern images being painted today. I particularly love his incorporation of stick figures. The clean, smooth lines that dance in Second Lines make me laugh even harder at people who exclaim “I can’t even draw a stick figure” as they parade from gallery to gallery. His works are, in themselves, art.

Eventually, I made it out of my small town, having mustered up the courage to venture to many of the beautiful places the world has to offer. But it wasn’t easy. You see, I found a way to cheat my limitations: I stayed close to one thing I tried to escape, yet I drew strength from that same thing as I ventured out. I returned to my small town when I needed a little safety. Limitations are simply the shackles you place on yourself. Knowing their presence is the one and only thing you need to shake them off and live the life you always knew you could. It’s as easy and as hard as that, and that makes the journey ever more rewarding.