May 01, 2019

From the French Quarter, visitors can see with their own eyes how New Orleans earned the nickname the “Crescent City” as large vessels follow the dramatic turn in the river upon which the early city was situated. The site of the original town was built in 1718 along the banks of “Old Muddy,” the Mississippi River's sweeping crescent-shaped bend. Ancient silt deposits from floods created ground higher than found in nearby swamps forming natural levees. In 1722, construction of a low levee was completed to help prevent flooding of the city. By the mid-1800s, wharves and warehouses were being built on the batture--the new land resulting from silt buildup, poles driven into the river’s banks to secure buildings, and ships docked along the levee.

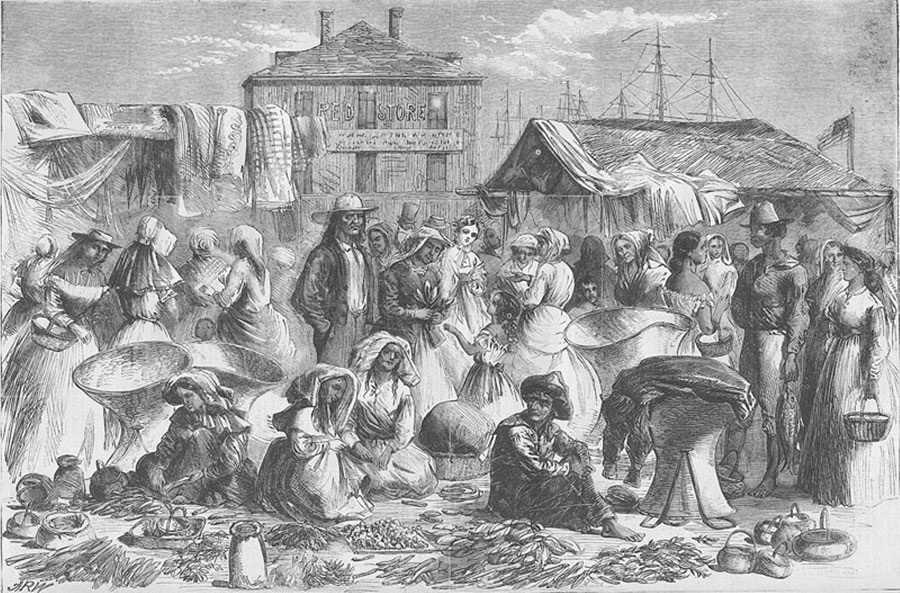

Native Americans traditionally traded on the riverbank near today's French Market, and early European settlers followed suit. Complaints of poor sanitation and price gouging prompted Spanish officials to build an enclosed, regulated market in 1779. After burning in the great citywide fire of 1788, the market was relocated to the area where today's market stands. On the edge of the river, ladders were extended down to boats where game, vegetables, and fish were sold. Other vendors set up shop on the levee using tables and umbrellas, and some African American slaves were allowed to sell produce they had grown.

The first steamboat, named New Orleans, reached the Crescent City in 1812, docking near Jackson Square. By the 1840s, the gravel walkway and trees were replaced by wooden piers jutting into the river. Sailing ships, flatboats, barges, and steamboats were so closely docked that people could possibly walk the rows of decks for miles without getting their feet wet. Each type of vessel was required to dock at a designated location. Steamboats docked from Jackson Square to beyond Canal Street, while downstream hosted oceangoing ships. In between, Lugger's Landing at the French Market was reserved for small boats carrying oysters and other market goods. Oyster luggers and flat boats sailing from the central portion of the United States delivered goods to the bustling market.

It was New Orleans’ position as a key port that attracted striving Americans to the quaint, Creole city during the nineteenth century. International vessels sailed upriver to dock and offload goods, restocking with cotton brought downriver on steamboats. Middlemen and merchants grew wealthy, and the commercial waterfront became increasingly privatized. By the 1860s, the piers had been replaced by a wide wooden wharf that was a crowded, animated world of carriages, carts, mules, horses, laborers, stevedores, traders, brokers and vendors stirring amid cotton bales, barrels of sugar, stacks of lumber, bananas, rum, cloth, and bags of coffee. There were also visitors coming off ships, steamboats, and trains. The wharf continued as a popular promenade, and in 1882 it became brighter when the city's first electric arc lights were installed along the Quarter's riverfront.

By 1891, sugar sheds, a sugar exchange, and a massive twelve-story sugar refinery stood near today's Canal Place. JAX Brewery, a unique New Orleans landmark, was once the brewing and bottling house of Jax Beer from 1891 until the mid-1970s. Today, the converted brewery holds exclusive and distinctive New Orleans shops and restaurants as well as nationally known retail stores.

Wharves were haphazardly leased until 1896, when a board of commissioners replaced open wooden wharves with covered wharf sheds that paralleled the river and blocked the view from the Quarter. The Quarter became even more cut off from the river in 1908 when the Public Belt Railroad was created alongside the wharves to help transfer goods between the wharves and other trains. The sugar refinery operations moved to nearby suburb Arabi in 1912, and the old building sat derelict until it was torn down in the 1940s to make way for parking lots. Several wharves were removed, opening part of the French Quarter up to the river, and the redevelopment of the area surrounding Jackson Square began in 1972. The streets around the square were turned into a pedestrian mall, while steep steps and an observation platform, now called Washington Artillery Park, were built across Decatur Street.

Between 1969 and 1972, United States astronauts made six landings on the moon, each one accompanied by a "moon walk." Though the promenade along the Mississippi River in front of Jackson Square called the Moon Walk dates from that approximate time, it was completed in 1976. Its namesake is not planet Earth's satellite, but a mayor of New Orleans, Maurice Edwin "Moon" Landrieu. Landrieu served two terms as mayor, from 1970 to 1978. Changing patterns of dockside cargo handling took place during the 1970s which eliminated the need for many traditional wharfs and created public access points to the Mississippi River. The Moon Walk was among the first of these large-scale promenades. As the Moon Walk nears its fourth decade of operation, it allows pedestrians unparalleled access to the Mississippi River in the heart of the city, and to an ever-changing panorama of water traffic and other activities.

The French Market’s location was no accident. Well into the 20th century, the ingredients that have made Creole cuisine world famous arrived in New Orleans by boat--not just Gulf oysters and shrimp for seafood gumbo, but also Central American coffee for cafe au lait and bananas for bananas Foster. Produce and seafood boats docked in this general area.

The Mississippi has always been a working river, and for generations most New Orleanians were cut off from any access to it by floodwalls, warehouses and very busy wharves. That began to change in the 1970s through the 1980s, as underused industrial buildings near the French Quarter were razed and replaced. In 1988, local philanthropists represented as the Dorothy and Malcolm Woldenberg Foundation presented a $5 million gift to the Audubon Institute for construction of a grassy, open space, Woldenberg Park, using the old Bienville Street Wharf. Dedicated in 1989, the park is adjacent to the Audubon Institute's Aquarium of the Americas, which opened in 1990. Today about half of the French Quarter's riverfront is open to the Mississippi, just as it was in the 18th and 19th centuries. Presently the area attracts an estimated seven million visitors annually.

In Woldenberg Park, you'll find bandstands with music, large grassy lawns, and many sculptures. My favorites include Robert Schoen’s Old Man River, a stone human figure made from Carrara marble. Weighing in at seventeen tons and standing eighteen feet high, the statue speaks to the river’s power and majesty in its rounded, circular body forms. Further downriver is the elegant and touching Monument to the Immigrant, crafted by sculptor Franco Allesandrini. The work faces the riverfront with a ship’s prow topped by a female figure reminiscent of Lady Liberty, while behind her stands a turn-of-the-century immigrant family looking toward the French Quarter. The most recent addition to this collection of public art is the city’s Holocaust Memorial, which was dedicated in 2003. Created by Israeli artist and sculptor Jacob Agam, the memorial is often described as a “living work” because its images and shapes change as one walks around it.

Just upriver from Woldenberg Park is the Spanish Plaza. Dedicated in 1976 during the U.S. bicentennial, the plaza was a gift from Spain in a gesture of friendship to its one-time colony. It features a large fountain ringed by tile mosaics of Spanish coats of arms representing that country’s provinces. Restaurants and shopping abound in this busy area of the city.

The Riverfront streetcar line opened August 14, 1988, making it the first new streetcar route in New Orleans in 62 years. The red line features a vintage look with modern amenities and runs two miles from Julia Street at the upper end of the New Orleans Convention Center to the downriver end of the French Quarter at the foot of Esplanade Avenue near the French Market.

Presently, landscape architects and urban designers are helping to reimagine the area between Crescent and Woldenberg parks and plan to transform former wharves into public space for recreation and festivals. When it all becomes a park, we will have a green ribbon of parks that go from the Bywater up to the Central Business District. We will have the largest contiguous riverfront park in the United States, a huge win for every resident and visitor of our city. This historic project will unlock a key stretch of land, expanding access for locals and visitors to enjoy river¬front access in a way that hon¬ors the original design of the city. Transforming the last two industrial wharves on New Orleans downtown riverfront will create over two miles of open space and will increase access for the community to enjoy the “front porch” of New Orleans. Upriver from the French Quarter, Crescent Park, a former wharf lost to a fire after Hurricane Katrina, has been transformed into a concert and event space and a trail winds along the water past elaborate contemporary gardens. With views of tugboats churning the water and ocean-going freighters rounding the river bend, the city’s evolving relationship with its riverfront is evident.

Riverwalk promenade space between St. Peter and St. Philip streets has recently undergone renovation, funded by the French Market Corporation. Developments include new walking surfaces, upgraded lighting, and better connection between the city and the river.

The New Orleans Four Seasons Hotel and Residences is presently in the process of renovation of our old World Trade Center. Expected to be complete in 2020, the 34-story building will have over 350 rooms on the lower floors, and 65 luxury condominiums on the upper floors. The developer also plans for the hotel to house a large cultural museum including exhibits and a theater which will be open to the public. A rooftop pool, restaurant, observation area, and Grand Ballroom with a view is included in their plans.

Stop and sit on one of the many benches of Woldenberg Park and watch the muddy waters flow by while the Steamboat Natchez toots out a version of "In the Good Old Summertime" on her calliope. It’s easy to imagine the bustling riverfront of years past.

Native Americans traditionally traded on the riverbank near today's French Market, and early European settlers followed suit. Complaints of poor sanitation and price gouging prompted Spanish officials to build an enclosed, regulated market in 1779. After burning in the great citywide fire of 1788, the market was relocated to the area where today's market stands. On the edge of the river, ladders were extended down to boats where game, vegetables, and fish were sold. Other vendors set up shop on the levee using tables and umbrellas, and some African American slaves were allowed to sell produce they had grown.

The first steamboat, named New Orleans, reached the Crescent City in 1812, docking near Jackson Square. By the 1840s, the gravel walkway and trees were replaced by wooden piers jutting into the river. Sailing ships, flatboats, barges, and steamboats were so closely docked that people could possibly walk the rows of decks for miles without getting their feet wet. Each type of vessel was required to dock at a designated location. Steamboats docked from Jackson Square to beyond Canal Street, while downstream hosted oceangoing ships. In between, Lugger's Landing at the French Market was reserved for small boats carrying oysters and other market goods. Oyster luggers and flat boats sailing from the central portion of the United States delivered goods to the bustling market.

It was New Orleans’ position as a key port that attracted striving Americans to the quaint, Creole city during the nineteenth century. International vessels sailed upriver to dock and offload goods, restocking with cotton brought downriver on steamboats. Middlemen and merchants grew wealthy, and the commercial waterfront became increasingly privatized. By the 1860s, the piers had been replaced by a wide wooden wharf that was a crowded, animated world of carriages, carts, mules, horses, laborers, stevedores, traders, brokers and vendors stirring amid cotton bales, barrels of sugar, stacks of lumber, bananas, rum, cloth, and bags of coffee. There were also visitors coming off ships, steamboats, and trains. The wharf continued as a popular promenade, and in 1882 it became brighter when the city's first electric arc lights were installed along the Quarter's riverfront.

By 1891, sugar sheds, a sugar exchange, and a massive twelve-story sugar refinery stood near today's Canal Place. JAX Brewery, a unique New Orleans landmark, was once the brewing and bottling house of Jax Beer from 1891 until the mid-1970s. Today, the converted brewery holds exclusive and distinctive New Orleans shops and restaurants as well as nationally known retail stores.

Wharves were haphazardly leased until 1896, when a board of commissioners replaced open wooden wharves with covered wharf sheds that paralleled the river and blocked the view from the Quarter. The Quarter became even more cut off from the river in 1908 when the Public Belt Railroad was created alongside the wharves to help transfer goods between the wharves and other trains. The sugar refinery operations moved to nearby suburb Arabi in 1912, and the old building sat derelict until it was torn down in the 1940s to make way for parking lots. Several wharves were removed, opening part of the French Quarter up to the river, and the redevelopment of the area surrounding Jackson Square began in 1972. The streets around the square were turned into a pedestrian mall, while steep steps and an observation platform, now called Washington Artillery Park, were built across Decatur Street.

Between 1969 and 1972, United States astronauts made six landings on the moon, each one accompanied by a "moon walk." Though the promenade along the Mississippi River in front of Jackson Square called the Moon Walk dates from that approximate time, it was completed in 1976. Its namesake is not planet Earth's satellite, but a mayor of New Orleans, Maurice Edwin "Moon" Landrieu. Landrieu served two terms as mayor, from 1970 to 1978. Changing patterns of dockside cargo handling took place during the 1970s which eliminated the need for many traditional wharfs and created public access points to the Mississippi River. The Moon Walk was among the first of these large-scale promenades. As the Moon Walk nears its fourth decade of operation, it allows pedestrians unparalleled access to the Mississippi River in the heart of the city, and to an ever-changing panorama of water traffic and other activities.

The French Market’s location was no accident. Well into the 20th century, the ingredients that have made Creole cuisine world famous arrived in New Orleans by boat--not just Gulf oysters and shrimp for seafood gumbo, but also Central American coffee for cafe au lait and bananas for bananas Foster. Produce and seafood boats docked in this general area.

The Mississippi has always been a working river, and for generations most New Orleanians were cut off from any access to it by floodwalls, warehouses and very busy wharves. That began to change in the 1970s through the 1980s, as underused industrial buildings near the French Quarter were razed and replaced. In 1988, local philanthropists represented as the Dorothy and Malcolm Woldenberg Foundation presented a $5 million gift to the Audubon Institute for construction of a grassy, open space, Woldenberg Park, using the old Bienville Street Wharf. Dedicated in 1989, the park is adjacent to the Audubon Institute's Aquarium of the Americas, which opened in 1990. Today about half of the French Quarter's riverfront is open to the Mississippi, just as it was in the 18th and 19th centuries. Presently the area attracts an estimated seven million visitors annually.

In Woldenberg Park, you'll find bandstands with music, large grassy lawns, and many sculptures. My favorites include Robert Schoen’s Old Man River, a stone human figure made from Carrara marble. Weighing in at seventeen tons and standing eighteen feet high, the statue speaks to the river’s power and majesty in its rounded, circular body forms. Further downriver is the elegant and touching Monument to the Immigrant, crafted by sculptor Franco Allesandrini. The work faces the riverfront with a ship’s prow topped by a female figure reminiscent of Lady Liberty, while behind her stands a turn-of-the-century immigrant family looking toward the French Quarter. The most recent addition to this collection of public art is the city’s Holocaust Memorial, which was dedicated in 2003. Created by Israeli artist and sculptor Jacob Agam, the memorial is often described as a “living work” because its images and shapes change as one walks around it.

Just upriver from Woldenberg Park is the Spanish Plaza. Dedicated in 1976 during the U.S. bicentennial, the plaza was a gift from Spain in a gesture of friendship to its one-time colony. It features a large fountain ringed by tile mosaics of Spanish coats of arms representing that country’s provinces. Restaurants and shopping abound in this busy area of the city.

The Riverfront streetcar line opened August 14, 1988, making it the first new streetcar route in New Orleans in 62 years. The red line features a vintage look with modern amenities and runs two miles from Julia Street at the upper end of the New Orleans Convention Center to the downriver end of the French Quarter at the foot of Esplanade Avenue near the French Market.

Presently, landscape architects and urban designers are helping to reimagine the area between Crescent and Woldenberg parks and plan to transform former wharves into public space for recreation and festivals. When it all becomes a park, we will have a green ribbon of parks that go from the Bywater up to the Central Business District. We will have the largest contiguous riverfront park in the United States, a huge win for every resident and visitor of our city. This historic project will unlock a key stretch of land, expanding access for locals and visitors to enjoy river¬front access in a way that hon¬ors the original design of the city. Transforming the last two industrial wharves on New Orleans downtown riverfront will create over two miles of open space and will increase access for the community to enjoy the “front porch” of New Orleans. Upriver from the French Quarter, Crescent Park, a former wharf lost to a fire after Hurricane Katrina, has been transformed into a concert and event space and a trail winds along the water past elaborate contemporary gardens. With views of tugboats churning the water and ocean-going freighters rounding the river bend, the city’s evolving relationship with its riverfront is evident.

Riverwalk promenade space between St. Peter and St. Philip streets has recently undergone renovation, funded by the French Market Corporation. Developments include new walking surfaces, upgraded lighting, and better connection between the city and the river.

The New Orleans Four Seasons Hotel and Residences is presently in the process of renovation of our old World Trade Center. Expected to be complete in 2020, the 34-story building will have over 350 rooms on the lower floors, and 65 luxury condominiums on the upper floors. The developer also plans for the hotel to house a large cultural museum including exhibits and a theater which will be open to the public. A rooftop pool, restaurant, observation area, and Grand Ballroom with a view is included in their plans.

Stop and sit on one of the many benches of Woldenberg Park and watch the muddy waters flow by while the Steamboat Natchez toots out a version of "In the Good Old Summertime" on her calliope. It’s easy to imagine the bustling riverfront of years past.