February 11, 2014

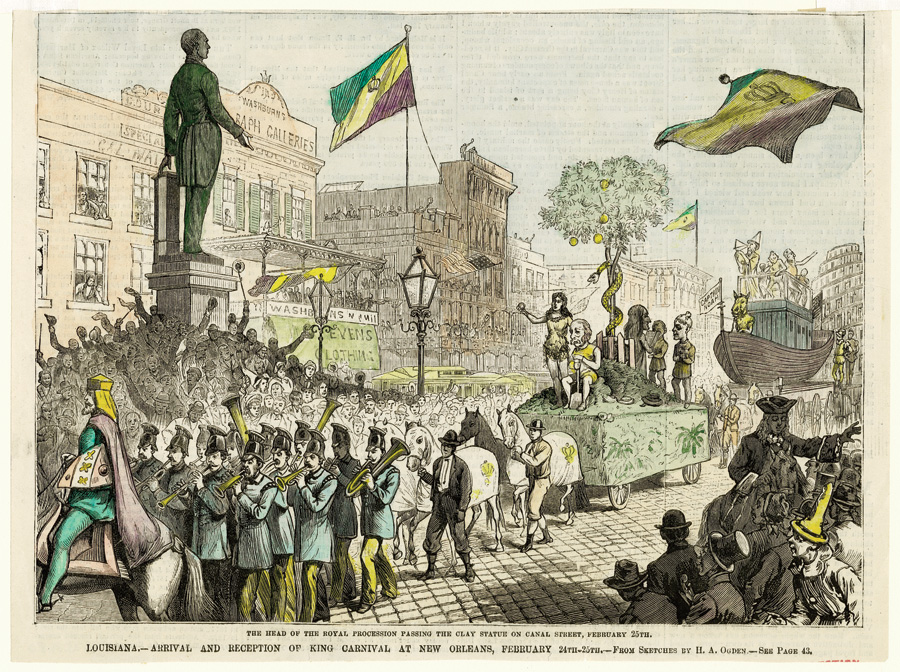

One of the most instantly recognizable architectural features in the French Quarter is the lacy ironwork that lines many of its narrow streets. For numerous Mardi Gras participants, the Quarter's ironwork balconies - which are attached to buildings and supported by brackets, as opposed to galleries, which cover the sidewalk and are supported by iron poles - are considered prime party space. Here partiers gather to watch the passing parade of street revelers and lavishly costumed marching groups, as well as toss coveted plastic beads to people begging for them from below. In recent years galleries have become notorious for people yelling out to others to "show us your "..." Although such display is strictly outlawed and can lead to arrest, some revelers risk disregarding the law to catch a strand - or "pair of," in local parlance - beads. Such illegal exposure got a boost in 1979; despite a city-wide police strike that prompted cancellation of Carnival parades in the city (though not the suburbs), huge crowds still thronged the French Quarter in picture-perfect weather, while the National Guard did little to police morals.

For many years, parades rumbled through the Quarter. Starting in the 1930s, parades would roll along Royal and Orleans Streets to the Municipal Auditorium at the end of Orleans in what is now Louis Armstrong Park, host to some of the city's oldest Carnival balls. The auditorium has been closed since Hurricane Katrina, awaiting restoration, and balls have moved to other venues like hotels and the Morial Convention Center. Because of fire danger parades were moved out of the Quarter in 1973, ending a beloved tradition of watching parades from balconies in the area's tight confines.

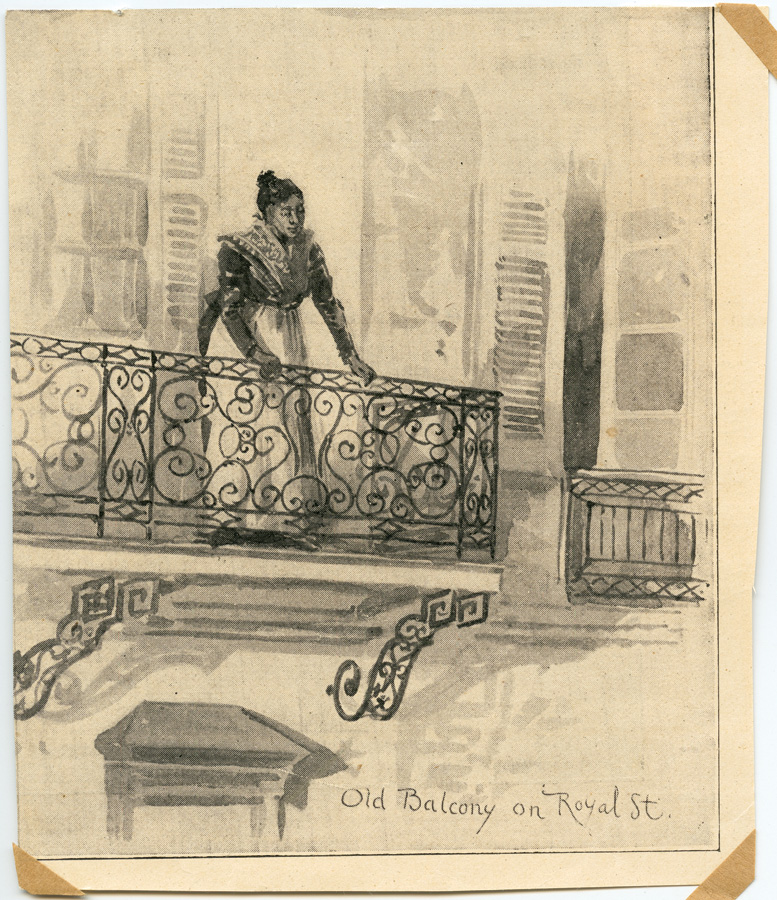

Of course, Mardi Gras gatherings are not the reason for the existence of so many galleries and ironwork in the Quarter. From the city's French colonial days, open spaces such as verandas were incorporated in building designs to allow an escape from indoors made stifling by hot humid summers. Two-story buildings often had covered second-floor galleries, giving upstairs living spaces access to fresh air, while providing a cover for ground-floor businesses. The first galleries in New Orleans were all built of wood; ironwork did not make an appearance here until the 1790s.

Louisiana was ruled by Spain between 1762 and 1803, and it was during this period that some of the most notable wrought iron designs appeared. Wrought iron is hand hammered, bent, and rolled to create elegant shapes. It was very expensive to produce and was used only for small balconies, gates, and railings on costly mansions and government and business buildings. Wood remained the material of choice for less extravagant buildings.

The ironwork of the Cabildo, erected 1795 - 99, is among the oldest in New Orleans. Other surviving examples include balconies on the late-1790s mansion on Royal and Conti (now housing Waldhorn and Adler Antiques) and another 1790s mansion at 417 Royal; in 1805 an iron balcony with the initials LB, for Banque de la Louisiane, was added when it became the state's first bank. There were a number of ironworkers in the city at the time, including whites, free people of color, and slaves who left their marks on French Quarter architecture. Among the most well known was Marcelino Hernandez, who was from the Canary Islands and whose work survives on the Cabildo and the Orue-Pontalba House at 600 St. Peter Street. The latter was completed in 1795 but reconstructed in 1963 as Le Petit Theatre, and now hosts Tableau Restaurant.

Cast iron changed the scene dramatically. Unlike wrought iron, this was not hand made, but molded and mass produced in foundries. This process allowed for the making of highly decorative and florid shapes that fit 19th-century tastes very well. Its cheaper cost allowed building owners to ring their properties with galleries.

By the 1850s lavish cast-iron galleries and balconies were becoming the norm on larger buildings and provided the prized lacy look in the Quarter we know today. Notable ironwork displays from this period are the galleries ringing the two Pontalba buildings, which face each other across Jackson Square. Cast in New York, the ironwork incorporates hundreds of times the initials of Micaela Almonester, the Baroness Pontalba, for whom they were built in 1849 - 51.

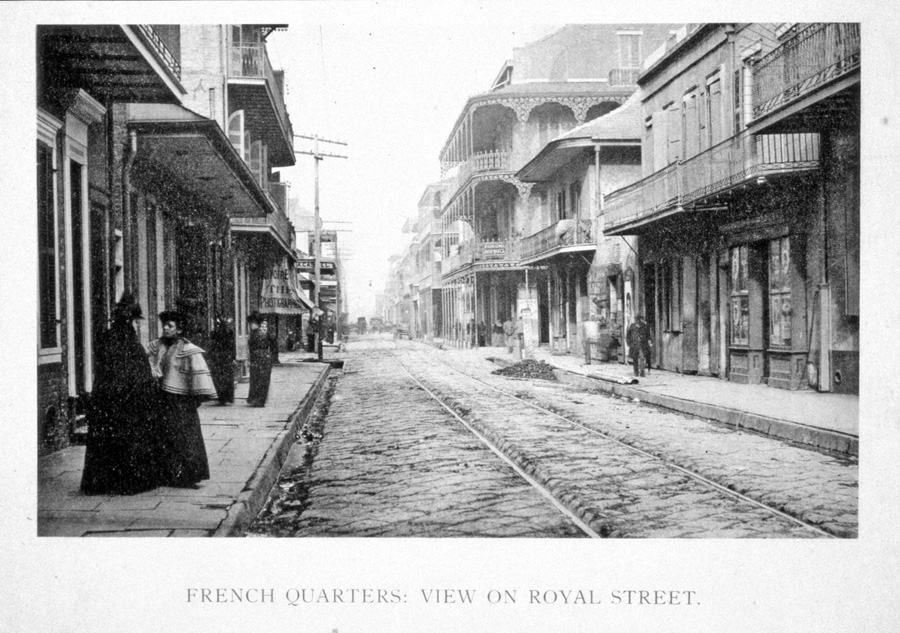

Much cast iron was made outside of New Orleans, and one of the notable manufacturers represented here was Wood and Perot of Philadelphia. Wood and Miltenberger were the New Orleans agents for the firm, and the Miltenberger House still stands today at 900 Royal. The unornamented brick townhouse was built in 1838; two other townhouses were later added to the complex, and the three were ringed with ironwork about 1850 - excellent advertising for the family business. Another Wood and Miltenberger product is the famous Cornstalk Fence, across Royal Street from the Miltenberger House. The same cornstalk pattern can be found in the Garden District extending about a quarter of a block around Colonel Robert H. Short's Villa at Prytania and Fourth Streets. Not to be outdone there were local foundries producing superb ironwork such as Pelanne Brothers, makers of the fence surrounding Jackson Square.

Another series of structures to which ironwork was added years after construction was the LaBranche Buildings. These eleven brick townhouses were built in 1840 along Royal and St. Peter Streets, and beginning in 1850, cast-iron galleries were added to them. The cast iron is in a different pattern for each building - and it is said that the corner of Royal and St. Peter is the most photographed corner in the Quarter.

Though today ironwork is most associated with the French Quarter, cast-iron galleries were a popular architectural feature throughout New Orleans. Fine examples may be found on Garden District mansions, some of which are by local foundries like Jacob Baumiller and John Armstrong. Ironwork galleries also lined business district streets, most notably the Canal Street shopping district between Chartres and Rampart Streets. These provided elegant ornamentation and sheltered shoppers from rain and sun, and at the time, Canal Street's galleries were among the city's leading Mardi Gras parade viewing sites. However, by the 1920s cast iron was out of fashion, and much of it was removed from Canal Street shops to provide a more streamlined, 20th-century look.

Though ironwork went out of fashion elsewhere and was stripped from business district buildings, it remained intact in the Quarter. By this time the Quarter was considered little better than a slum, and building owners were either unwilling or unable to keep up with the trends going on in wealthier parts of the city. Thanks to this, elaborate ironwork - one of the French Quarter's most enduring architectural assets - was preserved, essentially by neglect. In recent years the Quarter has gentrified. Ironwork is carefully protected and is frequently added to newer buildings. For example, Bourbon Street's Royal Sonesta Hotel, built in 1969, boasts ironwork reminiscent of that on the Miltenberger and LaBranche buildings.

Since 1971 the Royal Sonesta has ceremoniously had its gallery support posts greased with Vaseline by "celebrity greasers" - primarily local television and radio personalities - the Friday before Mardi Gras to dissuade daredevils from shinnying up the poles onto the galleries. Visitors will also find throughout the Quarter many galleries propped up with temporary wooden supports to help hold the weight of the extra people who crowd the Quarter in search of excitement during this time of year. Indeed, the Carnival season is one of the best times for visitors and locals alike to savor the French Quarter. Whether from high up on a balcony or from ground level, celebrants cannot help but recognize that they are surrounded by an architectural treasure.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center and publisher dedicated to the study and preservation of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. THNOC operates two facilities in the French Quarter. Guided tours, principal exhibitions, and the museum shop are located at 533 Royal Street, which is open Tuesday through Saturday, 9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m., and Sunday, 10:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. The institution's archives and research center as well as additional exhibition space, including the new galleries for Louisiana art, are available at 410 Chartres Street, which is open 9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Tuesday - Saturday. Many of the exhibitions and programs at The Historic New Orleans Collection are free and open to the public. For more information, visit www.hnoc.org or call (504) 523-4662.

For many years, parades rumbled through the Quarter. Starting in the 1930s, parades would roll along Royal and Orleans Streets to the Municipal Auditorium at the end of Orleans in what is now Louis Armstrong Park, host to some of the city's oldest Carnival balls. The auditorium has been closed since Hurricane Katrina, awaiting restoration, and balls have moved to other venues like hotels and the Morial Convention Center. Because of fire danger parades were moved out of the Quarter in 1973, ending a beloved tradition of watching parades from balconies in the area's tight confines.

Of course, Mardi Gras gatherings are not the reason for the existence of so many galleries and ironwork in the Quarter. From the city's French colonial days, open spaces such as verandas were incorporated in building designs to allow an escape from indoors made stifling by hot humid summers. Two-story buildings often had covered second-floor galleries, giving upstairs living spaces access to fresh air, while providing a cover for ground-floor businesses. The first galleries in New Orleans were all built of wood; ironwork did not make an appearance here until the 1790s.

Louisiana was ruled by Spain between 1762 and 1803, and it was during this period that some of the most notable wrought iron designs appeared. Wrought iron is hand hammered, bent, and rolled to create elegant shapes. It was very expensive to produce and was used only for small balconies, gates, and railings on costly mansions and government and business buildings. Wood remained the material of choice for less extravagant buildings.

The ironwork of the Cabildo, erected 1795 - 99, is among the oldest in New Orleans. Other surviving examples include balconies on the late-1790s mansion on Royal and Conti (now housing Waldhorn and Adler Antiques) and another 1790s mansion at 417 Royal; in 1805 an iron balcony with the initials LB, for Banque de la Louisiane, was added when it became the state's first bank. There were a number of ironworkers in the city at the time, including whites, free people of color, and slaves who left their marks on French Quarter architecture. Among the most well known was Marcelino Hernandez, who was from the Canary Islands and whose work survives on the Cabildo and the Orue-Pontalba House at 600 St. Peter Street. The latter was completed in 1795 but reconstructed in 1963 as Le Petit Theatre, and now hosts Tableau Restaurant.

Cast iron changed the scene dramatically. Unlike wrought iron, this was not hand made, but molded and mass produced in foundries. This process allowed for the making of highly decorative and florid shapes that fit 19th-century tastes very well. Its cheaper cost allowed building owners to ring their properties with galleries.

By the 1850s lavish cast-iron galleries and balconies were becoming the norm on larger buildings and provided the prized lacy look in the Quarter we know today. Notable ironwork displays from this period are the galleries ringing the two Pontalba buildings, which face each other across Jackson Square. Cast in New York, the ironwork incorporates hundreds of times the initials of Micaela Almonester, the Baroness Pontalba, for whom they were built in 1849 - 51.

Much cast iron was made outside of New Orleans, and one of the notable manufacturers represented here was Wood and Perot of Philadelphia. Wood and Miltenberger were the New Orleans agents for the firm, and the Miltenberger House still stands today at 900 Royal. The unornamented brick townhouse was built in 1838; two other townhouses were later added to the complex, and the three were ringed with ironwork about 1850 - excellent advertising for the family business. Another Wood and Miltenberger product is the famous Cornstalk Fence, across Royal Street from the Miltenberger House. The same cornstalk pattern can be found in the Garden District extending about a quarter of a block around Colonel Robert H. Short's Villa at Prytania and Fourth Streets. Not to be outdone there were local foundries producing superb ironwork such as Pelanne Brothers, makers of the fence surrounding Jackson Square.

Another series of structures to which ironwork was added years after construction was the LaBranche Buildings. These eleven brick townhouses were built in 1840 along Royal and St. Peter Streets, and beginning in 1850, cast-iron galleries were added to them. The cast iron is in a different pattern for each building - and it is said that the corner of Royal and St. Peter is the most photographed corner in the Quarter.

Though today ironwork is most associated with the French Quarter, cast-iron galleries were a popular architectural feature throughout New Orleans. Fine examples may be found on Garden District mansions, some of which are by local foundries like Jacob Baumiller and John Armstrong. Ironwork galleries also lined business district streets, most notably the Canal Street shopping district between Chartres and Rampart Streets. These provided elegant ornamentation and sheltered shoppers from rain and sun, and at the time, Canal Street's galleries were among the city's leading Mardi Gras parade viewing sites. However, by the 1920s cast iron was out of fashion, and much of it was removed from Canal Street shops to provide a more streamlined, 20th-century look.

Though ironwork went out of fashion elsewhere and was stripped from business district buildings, it remained intact in the Quarter. By this time the Quarter was considered little better than a slum, and building owners were either unwilling or unable to keep up with the trends going on in wealthier parts of the city. Thanks to this, elaborate ironwork - one of the French Quarter's most enduring architectural assets - was preserved, essentially by neglect. In recent years the Quarter has gentrified. Ironwork is carefully protected and is frequently added to newer buildings. For example, Bourbon Street's Royal Sonesta Hotel, built in 1969, boasts ironwork reminiscent of that on the Miltenberger and LaBranche buildings.

Since 1971 the Royal Sonesta has ceremoniously had its gallery support posts greased with Vaseline by "celebrity greasers" - primarily local television and radio personalities - the Friday before Mardi Gras to dissuade daredevils from shinnying up the poles onto the galleries. Visitors will also find throughout the Quarter many galleries propped up with temporary wooden supports to help hold the weight of the extra people who crowd the Quarter in search of excitement during this time of year. Indeed, the Carnival season is one of the best times for visitors and locals alike to savor the French Quarter. Whether from high up on a balcony or from ground level, celebrants cannot help but recognize that they are surrounded by an architectural treasure.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center and publisher dedicated to the study and preservation of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. THNOC operates two facilities in the French Quarter. Guided tours, principal exhibitions, and the museum shop are located at 533 Royal Street, which is open Tuesday through Saturday, 9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m., and Sunday, 10:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. The institution's archives and research center as well as additional exhibition space, including the new galleries for Louisiana art, are available at 410 Chartres Street, which is open 9:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Tuesday - Saturday. Many of the exhibitions and programs at The Historic New Orleans Collection are free and open to the public. For more information, visit www.hnoc.org or call (504) 523-4662.