August 01, 2016

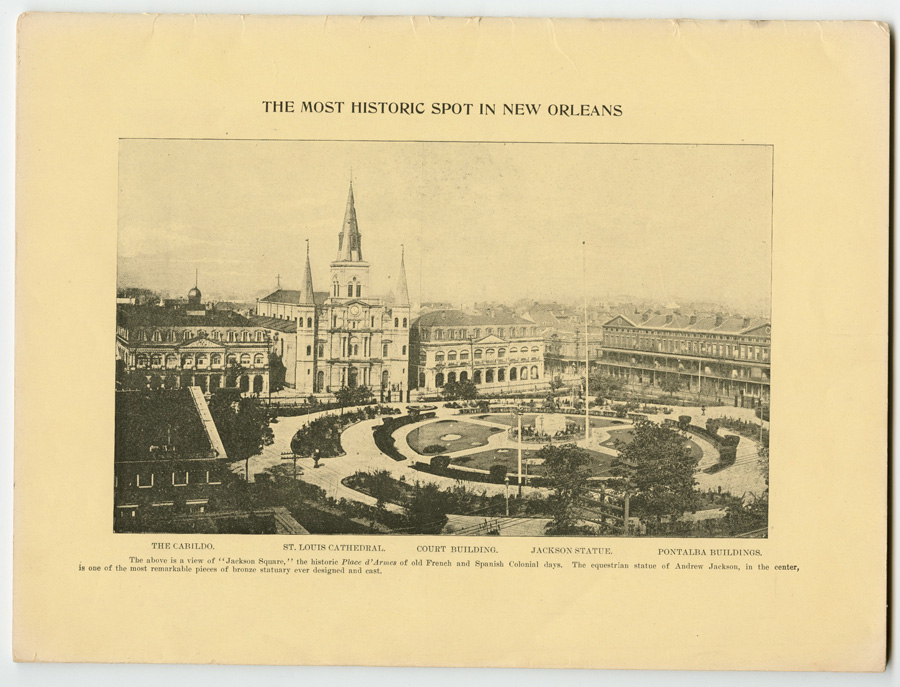

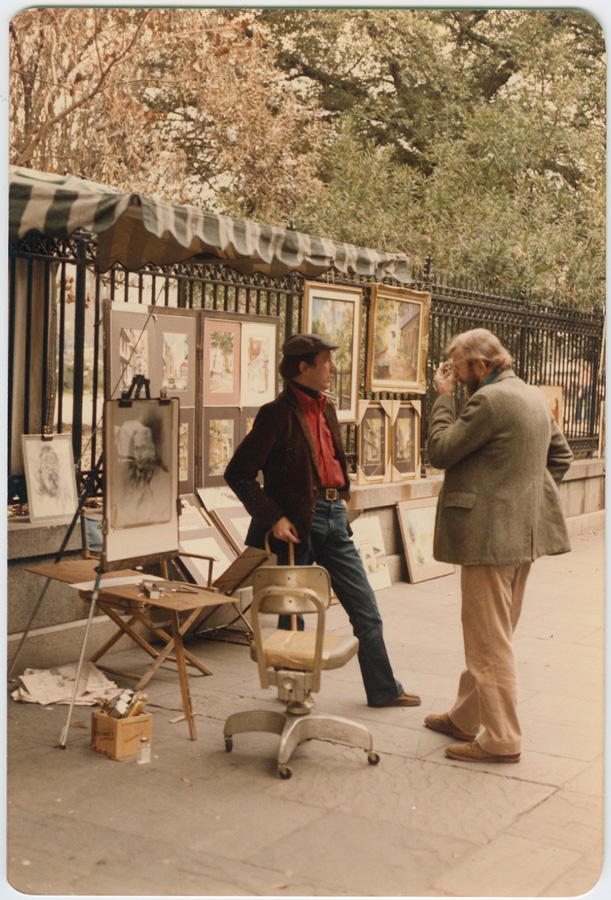

Jackson Square is in many ways the heart of the French Quarter. Today, as a public park and tourist destination, millions of people rest in its shade from the summer heat, taking in the splendor of the surrounding historic buildings and the Mississippi River. Park-goers can relax on the benches or lie on the grass admiring the regal statue of Andrew Jackson, honored for his role in saving New Orleans from the British during the 1815 Battle of New Orleans: Brass bands and fortune tellers line up en masse along the Chartres Street side calling out to people going in and out of the adjacent St. Louis Cathedral or the museums now housed in the Cabildo and the Presbytère, artists hawk their wares along the fence, and horse- and mule-drawn carriage tours line up along Decatur Street: the whole scene can be quite exhilarating, if not overwhelming. But over the years, this city block now known as Jackson Square has gone by a number of different names, has seen many different iterations, and has witnessed events of major historical importance. As peaceful or entertaining as it is now, it certainly hasn’t always been that way.

New Orleans was founded by Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville on the banks of the Mississippi River in 1718, although his engineer-in-chief for Louisiana (or a city planner in modern parlance) Pierre LaBlond de la Tour and assistant Adrien de Pauger did not arrive in New Orleans until 1721. In a plan dated April 23, 1722, they laid out a rough shape for the streets of the French Quarter, including a central square called the Place d’Armes, or a central plaza, around which the government buildings, including city hall, the governor’s house, and the parish church, would be built. In the early days of the city, the Place d’Armes, was a place for the people of the city to gather in celebration, for garrisoned troops to train, march, and parade, and also, occasionally, for criminals to be punished. In fact, the Place d’Armes, or the Plaza de Armas as it was known during the Spanish period, played an important role during the Spanish takeover of the city. In 1762 France ceded the Louisiana colony to Spain, but the new governor, Antonio de Ulloa, did not arrive until 1766. Ulloa, with only 90 soldiers, was unable to capture the support or loyalty of the majority French Creole population and by 1768 a conspiracy had developed that rallied 400 armed locals (some from outside the city) to a flag in the Plaza d’Armes. The gathered mob ran Ulloa out of town. The victory was short-lived, however: on August 18, 1769, a new governor, an Irishman named Alexander O’Reilly employed by the Spanish crown, arrived with 23 ships carrying 2,600 trained soldiers and landed directly on the Plaza. He executed the leaders of the conspiracy and firmly established Spanish rule over the city and the territory.

By 1803 the Spanish Crown had ceded the colony back to the French, and the French colonial Prefect Pierre Clement Laussat arrived in New Orleans early in the year to organize a new government. By August, however, he received word that the territory was being sold to the United States. Laussat received the official transfer of territory from Spain to France on November 30, 1803. Although the papers were signed in the Cabildo, the flags of the two nations were exchanged in the square in front of a crowd of townspeople. Just three weeks later, on December 20, 1803, Laussat oversaw the transfer of territory from France to the United States. The actual signing again took place in the Cabildo, but the Place d’Armes was filled with General Claiborne’s American troops. As Claiborne would later to write to then Secretary of State James Madison, “The Standard of my Country was this day unfurled here, amidst the reiterated acclamation of thousands. And if I may judge by the professions and appearances, the government of the United States is received with joy and gratitude by the people.”

In the following years the square saw anniversary celebrations commemorating the Transfer and also the Fourth of July, although 1815 was the year that changed the course for the future of Jackson Square, and really for the city itself. In January of 1815, General Andrew Jackson defeated an invading British Army at the Battle of New Orleans, on the Chalmette Battlefield right outside the city. It was one of the final military engagements of the War of 1812, and following the victory Jackson was declared “The Hero of New Orleans.” On January 23, 1815, a major celebration was held in the square including the construction of a grand, if temporary, triumphant arch, celebrating the general and his brave troops, with two children crowning Jackson with a laurel crown. At least one report holds that 12,000 people were there watching the celebration.

By 1820, the square was showing signs of neglect. When architect Benjamin Latrobe arrived that year he wrote, “The square itself is neglected, the fence ragged, and in many places open. Part of it is let for a depot of firewood, paving stones are heaped up in it, and along the whole of the side next to the river is a row of mean booths in which dry goods are sold…” Despite this decay, it was still the emotional and ceremonial center of the city. In 1825 the square held celebrations for the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette and solemn funerary rites commemorating the passing of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and in 1836 it hosted events celebrating the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s birth.

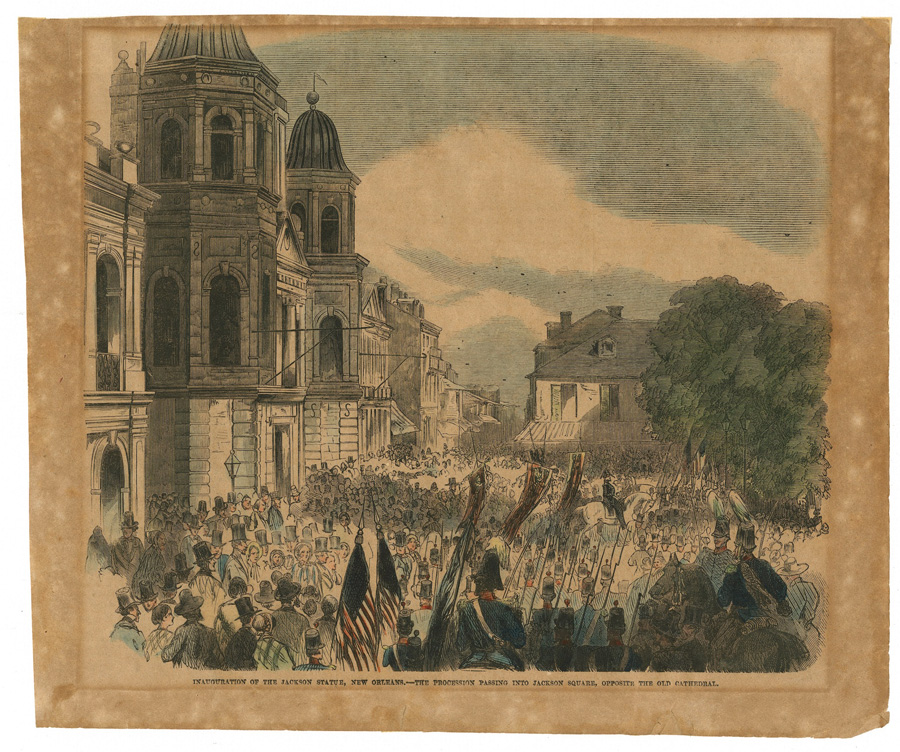

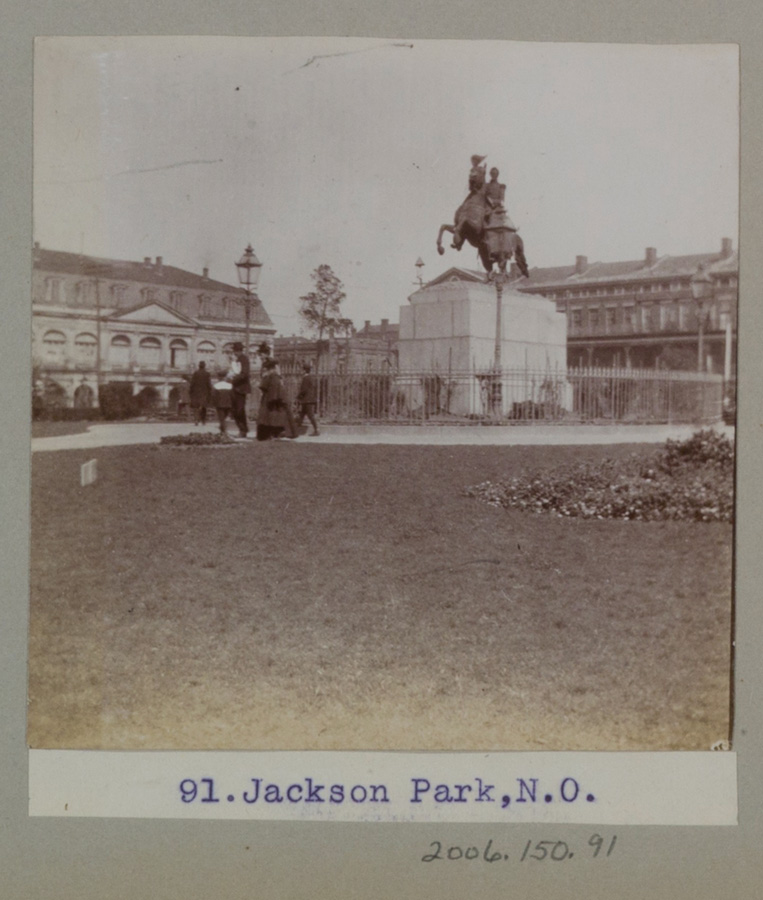

In 1840 Jackson visited New Orleans for the final time, to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans. During the celebration in the “Public Square,” as the area had come to be known during the early years of American control, Jackson laid a corner stone for a monument that would eventually be erected in his honor. By the late 1840s the square was in dire need of refurbishing, and the city established a special committee to oversee its renovation. Among other things, the committee officially adopted the name Jackson Square on January 28, 1851, and also oversaw the construction of the ornamental iron fencing that still surrounds the park today. That same year, an association was formed and charged with the task of finally completing the Jackson monument that had begun with the cornerstone nine years prior. Although cost was a major hurdle, eventually the association was able to commission sculptor Clark Mills (who had previously created an equestrian statue of Jackson in Washington, D.C.) for the job. The monument was finally officially dedicated in February of 1856. Later on, during the American Civil War, New Orleans was occupied by a Federal Army commanded by General Benjamin Butler. Butler had a stonecutter inscribe on the base of the monument a rough quote from Jackson—“The Union must and shall be preserved”—mostly out of spite toward the unruly New Orleans population bristling under the occupying force.

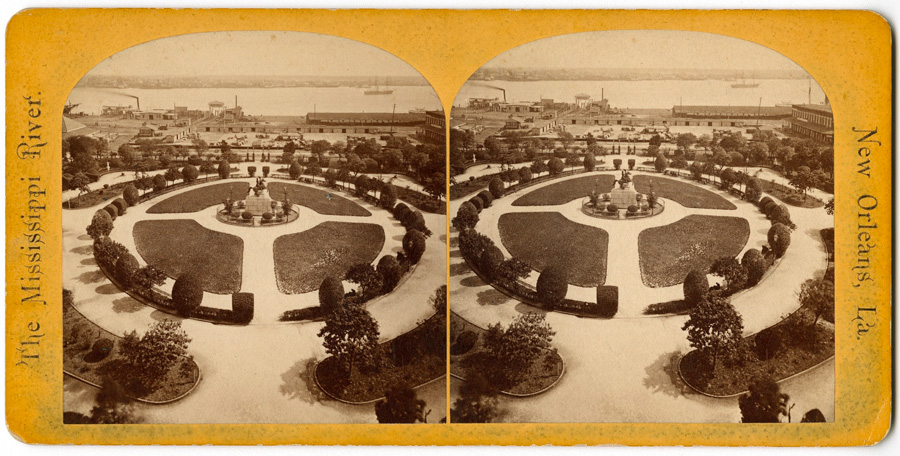

Today, the square itself still looks similar to the way it looked in the late 1850s, although the surrounding blocks, particularly the riverfront, have changed a great deal. In 1895 a fountain was added inside the park. It was later removed, and another fountain, the one that that exists today near Chartres Street, was built in 1960 to honor the visit of French President Charles De Gaulle. The square continued to be used for commemorations of important events throughout the 20th century: the 100th anniversary of the Louisiana Transfer in 1903, the centennial of the Battle of New Orleans in 1915, the 150th anniversary of the Purchase in 1953 (which was attended by President Dwight D. Eisenhower), and the square was refurbished ahead of the 250th anniversary of the founding of the city in 1968. In the 1970s pedestrian malls were created around the square removing traffic from Chartres, St. Peter, and St. Ann Streets, establishing Jackson Square’s modern image.

New Orleans was founded by Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville on the banks of the Mississippi River in 1718, although his engineer-in-chief for Louisiana (or a city planner in modern parlance) Pierre LaBlond de la Tour and assistant Adrien de Pauger did not arrive in New Orleans until 1721. In a plan dated April 23, 1722, they laid out a rough shape for the streets of the French Quarter, including a central square called the Place d’Armes, or a central plaza, around which the government buildings, including city hall, the governor’s house, and the parish church, would be built. In the early days of the city, the Place d’Armes, was a place for the people of the city to gather in celebration, for garrisoned troops to train, march, and parade, and also, occasionally, for criminals to be punished. In fact, the Place d’Armes, or the Plaza de Armas as it was known during the Spanish period, played an important role during the Spanish takeover of the city. In 1762 France ceded the Louisiana colony to Spain, but the new governor, Antonio de Ulloa, did not arrive until 1766. Ulloa, with only 90 soldiers, was unable to capture the support or loyalty of the majority French Creole population and by 1768 a conspiracy had developed that rallied 400 armed locals (some from outside the city) to a flag in the Plaza d’Armes. The gathered mob ran Ulloa out of town. The victory was short-lived, however: on August 18, 1769, a new governor, an Irishman named Alexander O’Reilly employed by the Spanish crown, arrived with 23 ships carrying 2,600 trained soldiers and landed directly on the Plaza. He executed the leaders of the conspiracy and firmly established Spanish rule over the city and the territory.

By 1803 the Spanish Crown had ceded the colony back to the French, and the French colonial Prefect Pierre Clement Laussat arrived in New Orleans early in the year to organize a new government. By August, however, he received word that the territory was being sold to the United States. Laussat received the official transfer of territory from Spain to France on November 30, 1803. Although the papers were signed in the Cabildo, the flags of the two nations were exchanged in the square in front of a crowd of townspeople. Just three weeks later, on December 20, 1803, Laussat oversaw the transfer of territory from France to the United States. The actual signing again took place in the Cabildo, but the Place d’Armes was filled with General Claiborne’s American troops. As Claiborne would later to write to then Secretary of State James Madison, “The Standard of my Country was this day unfurled here, amidst the reiterated acclamation of thousands. And if I may judge by the professions and appearances, the government of the United States is received with joy and gratitude by the people.”

In the following years the square saw anniversary celebrations commemorating the Transfer and also the Fourth of July, although 1815 was the year that changed the course for the future of Jackson Square, and really for the city itself. In January of 1815, General Andrew Jackson defeated an invading British Army at the Battle of New Orleans, on the Chalmette Battlefield right outside the city. It was one of the final military engagements of the War of 1812, and following the victory Jackson was declared “The Hero of New Orleans.” On January 23, 1815, a major celebration was held in the square including the construction of a grand, if temporary, triumphant arch, celebrating the general and his brave troops, with two children crowning Jackson with a laurel crown. At least one report holds that 12,000 people were there watching the celebration.

By 1820, the square was showing signs of neglect. When architect Benjamin Latrobe arrived that year he wrote, “The square itself is neglected, the fence ragged, and in many places open. Part of it is let for a depot of firewood, paving stones are heaped up in it, and along the whole of the side next to the river is a row of mean booths in which dry goods are sold…” Despite this decay, it was still the emotional and ceremonial center of the city. In 1825 the square held celebrations for the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette and solemn funerary rites commemorating the passing of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and in 1836 it hosted events celebrating the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s birth.

In 1840 Jackson visited New Orleans for the final time, to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans. During the celebration in the “Public Square,” as the area had come to be known during the early years of American control, Jackson laid a corner stone for a monument that would eventually be erected in his honor. By the late 1840s the square was in dire need of refurbishing, and the city established a special committee to oversee its renovation. Among other things, the committee officially adopted the name Jackson Square on January 28, 1851, and also oversaw the construction of the ornamental iron fencing that still surrounds the park today. That same year, an association was formed and charged with the task of finally completing the Jackson monument that had begun with the cornerstone nine years prior. Although cost was a major hurdle, eventually the association was able to commission sculptor Clark Mills (who had previously created an equestrian statue of Jackson in Washington, D.C.) for the job. The monument was finally officially dedicated in February of 1856. Later on, during the American Civil War, New Orleans was occupied by a Federal Army commanded by General Benjamin Butler. Butler had a stonecutter inscribe on the base of the monument a rough quote from Jackson—“The Union must and shall be preserved”—mostly out of spite toward the unruly New Orleans population bristling under the occupying force.

Today, the square itself still looks similar to the way it looked in the late 1850s, although the surrounding blocks, particularly the riverfront, have changed a great deal. In 1895 a fountain was added inside the park. It was later removed, and another fountain, the one that that exists today near Chartres Street, was built in 1960 to honor the visit of French President Charles De Gaulle. The square continued to be used for commemorations of important events throughout the 20th century: the 100th anniversary of the Louisiana Transfer in 1903, the centennial of the Battle of New Orleans in 1915, the 150th anniversary of the Purchase in 1953 (which was attended by President Dwight D. Eisenhower), and the square was refurbished ahead of the 250th anniversary of the founding of the city in 1968. In the 1970s pedestrian malls were created around the square removing traffic from Chartres, St. Peter, and St. Ann Streets, establishing Jackson Square’s modern image.